Why tech investors brave a wild ride for electric gains

9th December 2016 16:00

by David Prosser from interactive investor

Interactive Investor is 21 years old. To celebrate, our top journalists and the great and the good of the City have written a series of articles discussing what the future might hold for investors. Here's David Prosser on the trials, tribulations and rewards of being a tech investor.

It is easy to forget how much the world has changed over the past 21 years. In 1995 few people had access to the internet at home or at work, and most of those who did had to use a dial-up modem to get online.

was about to launch Windows 95, the first PC operating system to popularise home computing, while computers were rarely used outside a few industries.

Those people who did have PCs owned machines with roughly a tenth of the power of today's basic smartphones.

In other fields of technology, meanwhile, it would still be eight years until the human genome was fully sequenced, ideas such as electric vehicles and alternative energy were the preserve of hobbyists and geeks, and only a small minority of homes had access to anything other than a few terrestrial television stations. All TV signals were still analogue.

Patience rewarded

The advances of the past two decades have come in fits and starts - and investors in technology have endured a roller coaster ride.

However, the booms and busts belie the undoubted long-term potential of technology businesses for investors prepared to show real patience.

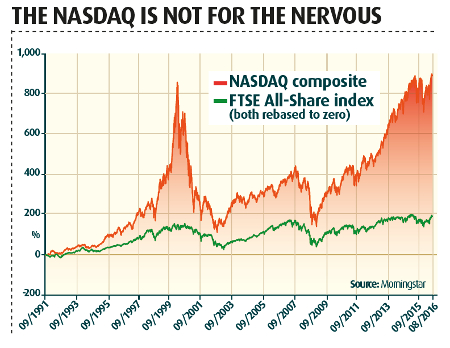

The NASDAQ index of US technology stocks has made a return of 593% since the beginning of 1995, though it took 15 years for the index to surpass its historic high point at the end of the dotcom boom in 2000.

In the UK, the FTSE TechMARK indices weren't launched until 1999, but the All-Share version has since returned more than 300%. Beneath these headline indices have been incredible stories.

The AOL-Time Warner merger of 2000 is now routinely called the worst deal in historyCambridge-based Arm Holdings floated in 1998 with an initial market capitalisation of £260 million.

Those investors who stuck around until this year, when Japan's Softbank agreed to pay £24.3 billion for the company, would have earned their initial stakes back almost 100 times over.

On the other hand, the - merger of 2000 is now routinely described as the worst corporate deal in history. The two companies lost close to $300 billion (£237 billion) of value during a painful marriage that ended in divorce via a demerger nine years later.

But at least both companies still exist, unlike, say, Pets.com, which floated at the start of 2000 and collapsed before the end of the year with losses of $147 million.

Huge capital outlays

These contrasting tales of spectacular success and dismal failure are rare in any other sector of the economy or financial markets.

But in technology, two factors combine: first, pioneers and innovators, by definition, gamble on the untried and untested; and second, such endeavours often require prolonged financial support before they become economically viable.

Investors can often stomach a string of losing bets if they enjoy the occasional big winner. The first dotcom phenomenon got going in 1997 and 1998 as entrepreneurs and investors began to recognise the commercial potential of the internet.

The era of the "new paradigm" urged investors to forget conventional valuation methods During a period of unusually low interest rates, money was available for investment in start-up companies seeking to exploit this potential, both from venture capitalists and from the investing public once businesses were ready to go to market.

Companies such as Freeserve and Lastminute.com in the UK, and , and even in the US, all shared one characteristic: they had little or no revenues to speak of and required huge capital outlays to get them profitable.

This was the era of the "new paradigm", when investors were urged to forget about conventional methods of valuing companies. For a time, investors bought the idea, and the subsequent success of some of the early dotcom darlings suggests it was not entirely without merit.

Boom and bust

But entrepreneurs got greedy and the claims became ever wilder. Investors became cynical - led by Warren Buffett, who point-blank refused to invest in technology.

By early 2000, sentiment had turned and the flotation of World Online marked the end of the party: within days, the company's shares were underwater. Within three years, the NASDAQ index was down 83%, while the TechMARK was off by 90%.

Survivors of the dotcom era had a long period of investor aversion, low resources and cost cutsMany firms had promising ideas, but internet technology wasn't yet sophisticated enough to execute them. Web connections were too slow and expensive. Cloud computing - offered then by application service providers - proved undeliverable.

And while people had begun to recognise the value of mobile channels, WAP, the forerunner of 3G and 4G, wasn't up to exploiting the potential of these ideas.

Those firms that survived the dotcom collapse suffered a prolonged period of investor aversion, limited resources and bone-rending cost cuts.

But the technology slowly began to catch up, and those early ideas started to come to fruition. The launch of Apple's iPhone in 2007 was one significant staging post in this process.

The financial crisis put everything on hold. Technology businesses that had finally begun growing suddenly found funding had dried up, while more mature companies closer to a stockmarket flotation had to postpone their plans. Quoted companies found their shares in freefall, along with the rest of the market.

The UK's most high-profile IPOs have included Worldpay, Sophos and Just EatIn time, the worst of the crisis passed and the past five years have seen a spate of technology company IPOs, starting with , , LinkedIn, , and Alibaba, and continuing over the past year or so with the likes of , , , and .

The UK's most high-profile IPOs have included , and . Then there are the technology giants that have so far chosen not to go public but nevertheless attract huge valuations - Airbnb and Uber, for example.

Inevitably, this period has been dubbed dotcom 2.0 - and many valuations certainly look very heady.

A new bubble?

So are we in a new technology bubble? Well, some of the most high-profile IPOs of recent years have disappointed investors - even Facebook shares have traded below their issue price for long periods.

The bullish case, however, is that unlike 15 years ago, many technology companies now have proven revenue models and a lot of them are very profitable, not least because this time, the technology behind the hype - from cloud computing to e-commerce - works.

There will be more failures and, to some extent, the technology sector relies on a boom-and-bust cycle, as start-ups and entrepreneurs need periods of over-investment as they pan for gold.

But while investors should not expect a smooth ride; in 21 years' time there will be equivalents to Google and Arm, delivering just as impressive returns.

This article was first published in our special publication 21: Twenty-one years of Interactive Investor. Download your digital copy for free here.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser