How to survive a market crash

27th September 2018 11:30

by Faith Glasgow from interactive investor

Amid all the fuss around trade wars, rising interest rates and the end of a record-breaking bull market, Faith Glasgow tells us the best way to tackle a market meltdown.

The 10-year anniversary of the collapse of Lehman Brothers, which precipitated the global financial crisis in mid-September 2008, has provided a great opportunity for the financial services industry's statistics geeks to wheel out some impressive figures demonstrating the power of long-term equity investment to dull the pain of market crashes – and the extent of people's capacity to be wise after the event.

For example, Ben Yearsley at Shore Financial Planning points out that someone who had invested in a simple FTSE All-Share index tracker fund just before the Lehman debacle would have enjoyed a 118% rise to mid-September 2018, despite it losing a third of its value in the six months following the bank's bankruptcy. If they'd gone for a FTSE 250 index tracker, they'd have done even better, with gains of more than 200% over 10 years – though they too would have had to cope with a stomach-churning fall of around a third in the value of their portfolio in the last quarter of 2008.

Certainly, equities have been the place to be in the interim, as markets have been fuelled by central banks pouring money into the financial system through their quantitative easing (QE) programmes to stem the economic meltdown.

Patchy picture for equities

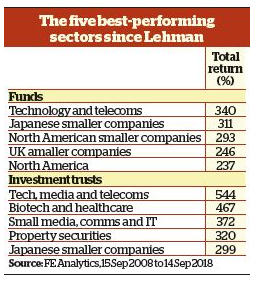

While index trackers have performed strongly on the back of a 10-year bull market, drilling down below the upbeat headline figures reveals a more nuanced story. The most successful fund sectors (see table) have been driven by powerful factors not directly connected with the aftermath of the financial crisis: the global technology explosion, the inherent capacity of smaller businesses to grow faster than big ones and the protectionist measures imposed by president Donald Trump being the most obvious ones.

The outperformance of specific sectors is even more pronounced for investment trusts: their closed-ended structure, narrowing discounts and ability to gear have all helped fuel already prospering sectors. But at the other end of the spectrum, vulnerable specialist sectors such as forestry, commodities and (surprise, surprise) financials have patently failed to recover to anything like pre-crisis levels.

More generally, as the Association of Investment Companies observes, investment trusts have been a strong bet since the financial crisis, despite their tendency to suffer more in market downturns than their open-ended peers. The AIC calculates that from the very top of the market on 12 October 2007, the average trust has gained 147%. In comparison the average unit trust is up 92%, according to Morningstar. To give a sense of the extent of the losses they had to absorb in the process, from that date to the low point on 3 March 2009, the FTSE 100 index lost 48%.

Overall, the message behind the stats is clear: timing the market is a mug's game, so sensible investors should hold their nerve and take a long-term view in the face of market turbulence.

That's sound advice in the normal course of market ups and downs. But hindsight is a wonderful thing: 10 years ago the UK - indeed the world - was teetering on the brink of financial implosion as banks tumbled like ninepins. The then chancellor of the exchequer, Alastair Darling, recently told the BBC that when he stepped in to bail out Royal Bank of Scotland, then the biggest bank in the world, in autumn 2008, it was 'haemorrhaging money' and was set to run out of cash that afternoon.

The crisis was widely viewed as the precursor to another Great Depression. Politicians were desperately trying to work out ways to prop up the global banking system. The media headlines were apocalyptic.

So I suspect most investors who sat and watched the value of their portfolio lurch south were not remaining calm and focusing on the long-term view, but caught in an agony of indecision as to whether to bite the bullet and bail out or hold on blindly, hoping that global institutions would somehow find a way to avert catastrophe.

In the event, expansionary QE policy that provided a powerful stimulus for global equity markets, together with other drivers such as the tech boom, means those investors able to leave their money in the market for the full decade have done pretty well as a consequence of their paralysis. Ultimately, though, the success of simply sitting out market meltdown as a strategy must depend on how long you can afford to wait for your money, and how much pain you can bear in the meantime.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.