Smithson one year on: is Terry Smith's fledgling trust going to fly?

A year after its highly successful launch, Andrew Pitts asks if Smithson investment trust will succeed w…

29th November 2019 12:49

by Andrew Pitts from interactive investor

A year after its highly successful launch, Andrew Pitts asks if Smithson investment trust will succeed where other high-profile newcomers have failed.

High-profile, large investment trust launches have a nasty habit of not ending well for eager private investors in thrall to the cult of a ‘star manager’ or attracted to an investment story that turns out to be less exciting than first thought.

The ongoing travails for investors in Woodford Patient Capital (WPCT), which raised £800 million in April 2015, are the most recent consequences of this tendency. It begs the question whether investors in Smithson Investment Trust (SSON) – which became the largest ever investment trust launch last October, raising £822 million – risk a similar fate. But first, a potted history.

- 40 years of investing: is this the end of easy money?

In 1994 the £549 million raised by Mercury European Privatisation broke all the records, although Kleinwort European Privatisation’s fundraising a month earlier was heavily oversubscribed and came pretty close, raising £481 million. In today’s money, these launches were actually larger than WPCT and Smithson (the retail prices index has risen by 106% over the intervening quarter century).

Plot twist

Both trusts had a good story to tell: the expectation of vast profits to be made from the mass privatisation of European state-owned enterprises. But this investment story had an unhappy ending. The Kleinwort trust was wound up around two years later; the Mercury version went through various incarnations before also being wound up a decade later.

The £460 million launch of Fidelity China Special Situations (FCSS) in 2010 certainly captured the investing public’s imagination but was also controversial. This was to be feted fund manager Anthony Bolton’s swan song. He had come out of retirement to run the trust, having been excited about corporate China’s prospects after enjoying leisure time in Hong Kong.

Just as Neil Woodford over-reached himself by believing he had the necessary expertise to manage a somewhat rag-tag portfolio of unquoted, early-stage investments, so too did Bolton. The latter found the challenges of investing in China, as many (including Money Observer) had predicted, far more difficult than investing in the UK, his previous stamping ground.

When Bolton went back into retirement in 2014 and handed the reins to Dale Nicholls, FCSS’s current and highly rated manager, he was reported to have said that “the Chinese are great liars”. In his fouryear tenure, the shares gained less than 10%. In fairness, FCSS did actually get off to a good start, which helped it attract another £166 million from eager investors in February 2011, after which the net asset value plummeted.

Like the Fidelity trust, Smithson has also raised extra capital from eager investors in its first year: a quite staggering £325 million, on top of the £822 million it raised at launch. What makes this all the more impressive is that Smithson’s initial target fundraising was just £250 million.

Today, Smithson’s total assets have grown to £1,394 million. The shares trade on a small premium (currently around 3%) to net asset value, which means its market capitalisation as of 4 November is £1,435 million, according to the Association of Investment Companies.

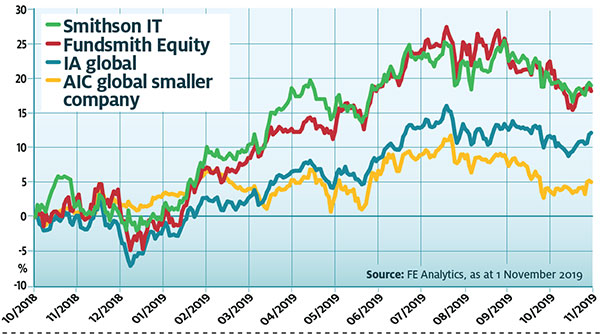

Untroubled trajectory so far for Smithson

Novel narrative

Can Smithson succeed where other high-profile trust launches failed? The record amount it raised undoubtedly had a lot to do with the cachet of Fundsmith Equity manager Terry Smith. However, what makes Smithson different from other trusts launched on the back of a star reputation is that Smith does not manage the trust himself.

Smithson’s portfolio managers are Simon Barnard and Will Morgan – certainly not household names among the investing public. The duo, who sharpened their investing spurs at Goldman Sachs, have kept their heads down and have so far delivered on the Fundsmith mantra of investing in quality companies at sensible prices and then doing nothing. Smith himself, the firm’s chief investment officer, acts as éminence grise: he is involved only when big outright selling and purchasing decisions are made.

The strong implication is that – unlike the launches of trusts for names such as Bolton and Woodford, or on the back of themes such as China or privatisation – the Smithson launch offers investors the proven benefits of Fundsmith Equity’s investment process. For Smithson this is applied to global small and medium-sized companies, rather than to the corporate behemoths that its larger sister – now with assets of £18 billion under management – targets.

Proven process

So far this investment process has contributed to a gain of 18% (as at 4 November) at the portfolio level since Smithson’s launch, in line with Fundsmith Equity’s 18.2% gain over the same period.

What both have in common is a very strong focus on free cash flow yield. But why does the team attach such importance to this valuation metric? Barnard argues: “First, because present and future cash flow is the only measure that actually determines the value of a standalone company, it makes sense to us to use it for our own valuation. Secondly, cash flow is the hardest measure for a company management team to manipulate, and so by focusing on this, we can take some reassurance that we are observing what is actually going on fundamentally in the business.”

Fundsmith tends not to pay too much attention to macro events, market index movements and what’s going on in other asset classes. But Barnard, like many investors, cannot readily see why investors are still willing to buy bonds, including corporate bonds, which offer a negative yield.

However, he argues, the practice is supportive of equities in general. “A lower interest rate environment will benefit almost all asset prices, and in particular share prices where corporate earnings grow over time. For the corporates issuing bonds at a negative yield, they will also have the benefit of becoming slightly more profitable, although the effect on their share price will be outweighed by the valuation effect of the low-rate environment in general.”

But doesn’t the widely used practice of using debt to fund buybacks and dividends distort investors’ perceptions of corporate health? Barnard says that in some instances, it can be beneficial to use low-cost debt to fund buybacks, if it is the best use of capital; or dividends, if there are no investment opportunities for the company internally or externally.

“But the amount of cheap debt that has been used for dividends and buybacks, especially in the US, could be deemed excessive in some cases and can serve to support the share prices of companies suffering from poor fundamentals,” he adds. “This of course cannot continue indefinitely, as eventually such companies will be unable to support the debt pile that has been loaded on them.”

Definitely not the sort of company you will find in Smithson’s portfolio, given the company’s motto: Small and Midcap Investments That Have Superior Operating Numbers.

Smithson’s big winners and little losers

The timing of Smithson’s launch last October was propitious. When the market sold off towards the end of 2018, the trust was able to buy high-quality companies at “very reasonable valuations”, says Simon Barnard.

He highlights data analytics and risk management firm Verisk Analytics and Masimo, a medical device manufacturer, as among the most successful. He says: “They are two of our highest-quality companies, given their dominant market positions, recurring revenue streams and growth opportunities. We made them among our top five positions at the time and they have added the most value to the portfolio since.”

A few of the holdings have lost value. Barnard says this has tended to be due to a significant change for the worse since such a holding was bought, as with software company CDK Global. Barnard says: “A new chief executive officer was brought in last year and changed the company strategy, causing us concern over future capital allocation. Because of this fundamental change, we sold the position earlier this year.”

Andrew Pitts invests in Smithson and Fundsmith Equity. He was editor of Money Observer from 1998 to 2015.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.