The UK's coming mortgage crunch

11th July 2023 09:16

by abrdn Research Institute from Aberdeen

The changing structure of the UK mortgage market has slowed the transmission of monetary policy to the economy. But the recent surge in mortgage rates should quickly dull housing activity and is set to impact the large stock of mortgages due to refinance in the coming months. We expect this to lead to a recession by Q4 this year.

Key Takeaways

UK mortgage rates have surged as market expectations of the path of Bank Rate have moved higher.

But the huge shift in the UK mortgage market towards fixed-rate mortgages has slowed the transmission of monetary policy to existing mortgages.

Indeed, only around one-third of the impact of tighter monetary policy has so far been felt by the economy.

The large stock of mortgages due to be refinanced in the coming months will mean a big increase in economy-wide mortgage servicing costs. We think this will tip the economy into recession by Q4 this year.

The key risk to this forecast is that the government introduces significant mortgage market interventions well beyond the scope of the recently announced “Mortgage Charter”. This would cause interest rates to stay higher for longer.

UK mortgage rates have jumped higher

The recent run of disappointingly high inflation data has seen market expectations for the future path of Bank Rate reprice significantly higher. We added 100 basis points (bps) to our forecast of where interest rates will peak and now see Bank Rate reaching 5.5%. We also now expect a slower, shallower cutting cycle compared to our forecasts immediately before the April inflation report. Moreover, the risks are skewed to the upside, with the market pricing in a terminal rate above 6%.

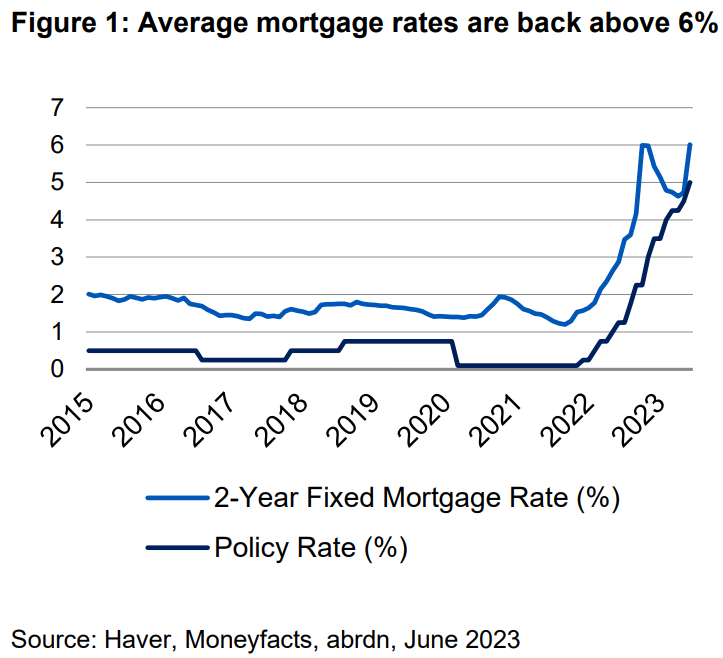

This spike in market interest rates has led to an increase in mortgage rates, with the average interest rate on two-year fixed deals increasing above 6%, revisiting levels last seen in October 2022 following the ill-fated Truss/Kwarteng budget (see Figure 1).

The speed of monetary transmission has slowed

Monetary transmission works through a broad range of channels including asset prices, exchange rates, and expectations. It is important not to overly focus on mortgage rates in considering the full impact of monetary policy.

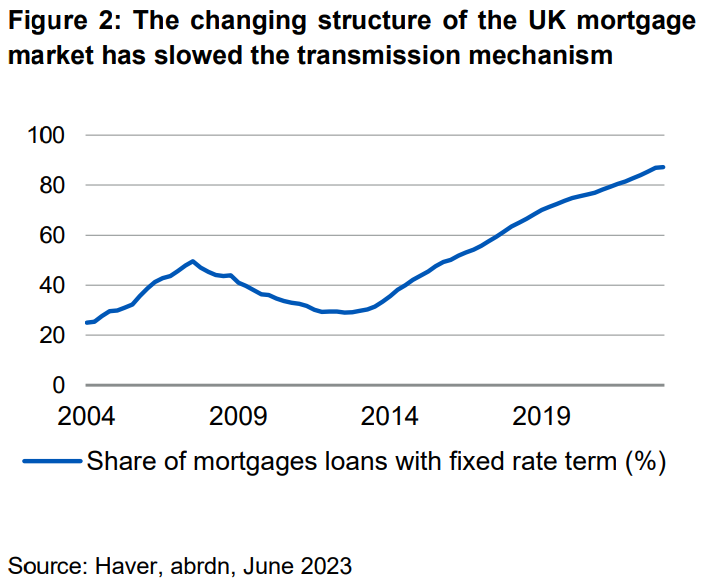

However, there have been important changes to the structure of the UK mortgage market over the last 25 years that have impacted the speed of monetary transmission.

The stock of mortgages on fixed rates has increased from around 30% in 2012 to around 85% now (see Figure 2). Meanwhile, the average tenor of mortgage fixes has increased.

By comparison to the mortgage markets in the US and much of continental Europe, the UK still has relatively short fixes. But these changes mean that it now takes longer for the full impact of monetary policy to be felt by the economy.

Estimating the speed of monetary transmission is notoriously difficult. However, a huge stock of variable-rate mortgages meant that these lags were once relatively short, with the Bank of England (BoE) estimating in 1999 that the full impact of changes in policy were felt within a year. However, in a recent speech Bank of England deputy governor Ben Broadbent suggested that, while uncertainty about the lag has increased, it is now likely to be around two years.

The slower pace of monetary transmission helps explain some of the resilience of the economy. While the underlying pace of activity has essentially flatlined, this is better than the recession many were forecasting. Indeed, the IMF recently revised up its UK growth forecasts, removing its expectation that the economy would enter a recession this year.

We have long been sceptical of this optimism, and the further leg higher in interest rates increases our conviction that the UK is heading towards a recession. But given the changes to monetary transmission, it is useful to set out how we see rising mortgage rates impacting the economy.

Higher mortgage rates feed into housing activity rapidly

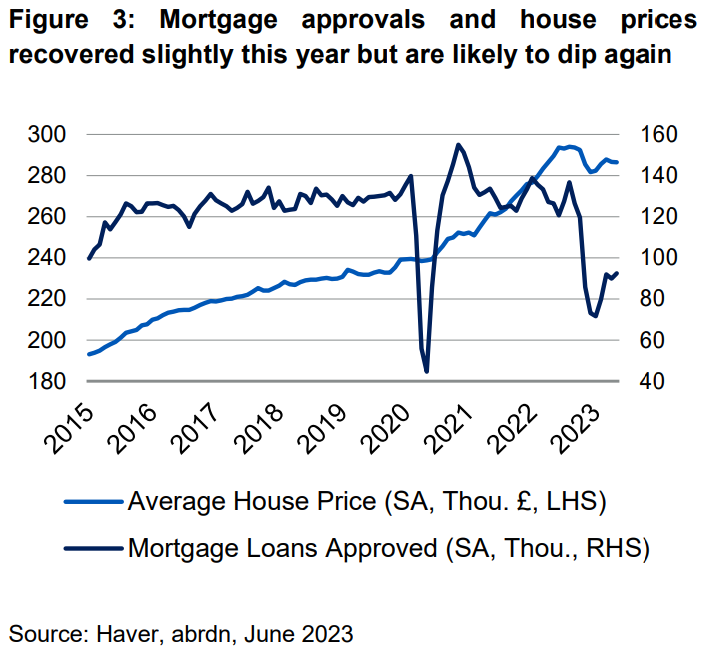

With around two-thirds of housing transactions financed by mortgages, higher mortgage rates are almost immediately felt in housing activity data.

Following the surge in mortgage rates last year, mortgage approvals fell sharply (see Figure 3) but they have since recovered slightly in line with the decline in mortgage rates through Q1 this year.

However, with mortgage rates now returning to the highs of last year, approvals are likely to revisit the recent lows. This fall in mortgage approvals and transactions should show up quickly in house prices as sellers work harder to find the marginal buyer.

For example, Zoopla has reported a surge in sellers accepting at least a 5% discount on sale prices in the last two weeks. Significant further national declines are likely as this housing activity channel of higher mortgage rates continues to play out.

The impact on existing mortgages takes longer

While new mortgage rates have increased sharply, BoE data shows that the average effective rate on the existing stock of mortgages has only risen by 70bps since the hiking cycle started. This reflects the fact that 85% of mortgages are now fixed and so it takes time for these rises to impact existing mortgages.

Analysis by the Resolution Foundation suggests that at the end of June 2023, only around 50% of mortgaged households will have seen their mortgage rate change since the Bank starting hiking rates. In aggregate, they calculate that annual mortgage repayments have increased by £6.3 billion. This is an average increase of £1,500 for affected households.

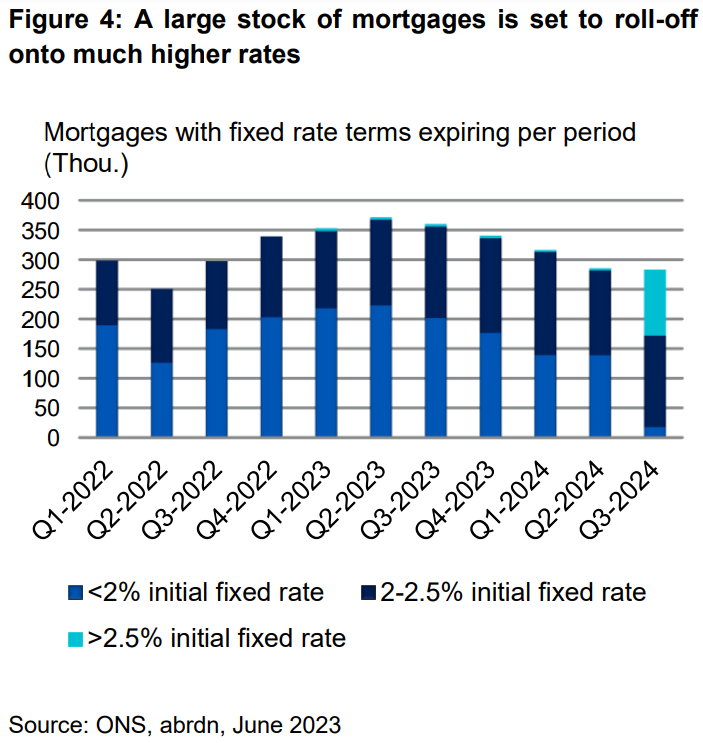

However, over coming months, the stock of mortgages set to roll off will increase significantly, with households facing sharply higher financing costs (see Figure 4). This reflects the impact of the stamp duty holiday that ended in 2021, when anticipation of the return to higher tax rates caused an increase in housing activity. Two-year fixes taken out to finance those purchases are now set to roll off at much higher rates.

The Resolution Foundation estimates that there is a further £9.5 billion increase in mortgage repayments still to come. This means that only around one-third of the total impact of the mortgage squeeze has been felt so far. This is broadly consistent with the BoE’s estimate of the extent of monetary tightening transmitted to the economy.

At the household level, monthly mortgage repayments will rise by nearly 50% on average, which is above the typical stress-tests households are subjected to when applying for a mortgage. For a typical mortgagor, the rise in rates in 2023 alone is expected to increase repayments by 3% of household income. This is the biggest annual hit to incomes in almost 50 years, and in the past has been more than enough to send the economy into a recession.

The big difference compared to the previous 50 years is that this time the hit to households will be more narrowly felt. The percentage of households with a mortgage has fallen from 40% in the early 1990s to 30% now. We estimate the shock is still more than enough to trigger a recession, albeit not as large as the roughly 2.5% peak to trough fall in GDP in the early 1990s, when the mortgage shock to households was smaller in disposable income terms but more widespread across the population.

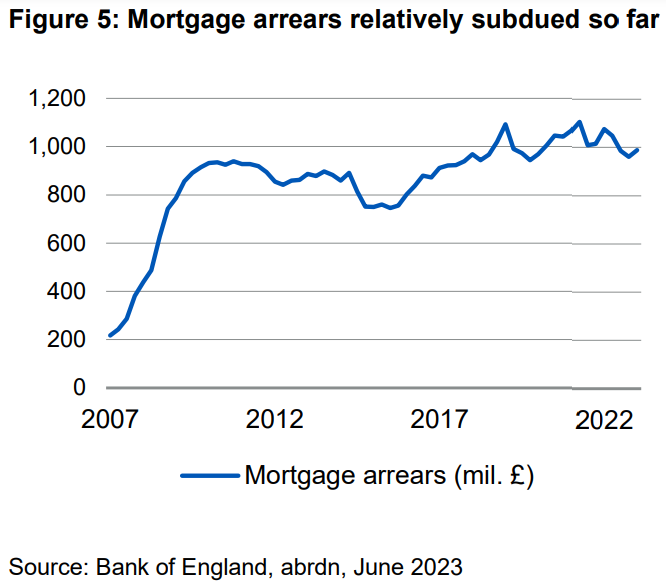

Mortgage distress is a lagging not leading indicator

So far, signs of mortgage distress have been pretty modest. There has been a slight pick-up in repossessions, but from an extremely low level. And there has been little change in the amount of mortgage arrears (see Figure 5).

The rise in mortgage rates is unlikely to lead to a surge of repossessions in the first instance. Households tend to sacrifice other consumption choices to continue servicing mortgages.

And as demonstrated by the recently announced “Mortgage Charter”, both banks and the government have an interest in extending forbearance to avoid a surge in repossessions.

But it is precisely the choice of households to divert spending towards servicing higher mortgage costs that helps deliver the wider economic impact of tighter policy. As consumption falls, this transmits economic weakness to the rest of the economy and eventually causes an increase in unemployment. This higher unemployment then helps to ease inflation pressures as labour market heat dissipates.

It is only once unemployment rises significantly that repossessions become a bigger part of the story, as it is the loss of income outright that makes mortgages unserviceable, not higher costs at the margin. So we should not look to repossessions or arrears data as an early warning indicator or take particular comfort from these indicators remaining subdued for the time being.

Higher mortgage rates aren’t inflationary via higher rents, in equilibrium

There has been some concern that rising mortgage rates are causing rental prices to increase, as landlords pass on higher financing costs to tenants. The worry then is that higher mortgage rates are inflationary because of this impact on rental prices.

Certainly, rental prices have been increasing rapidly at the same time as interest rates. But concerns about the causal connection between the two seem misplaced for several reasons.

First, landlords don’t get to set rental prices based on their costs alone. It is the rapid pace of wage growth (combined with Britain’s perennial housing supply problems), that has allowed landlords to charge higher rents. Put simply, renters can afford higher rents as wage growth is higher. Rising rental prices are better seen as part of the phenomenon of high inflation rather than causing inflation.

Second, even if higher mortgage rates did push up rental prices, this does not mean it would be inflationary in general equilibrium. Higher rental prices represent a flow of income away from households with higher marginal propensities to consume (i.e. tenants) towards households with lower marginal propensities to consume (i.e. landlords). That means less spending on all other goods and services in the economy. So while rental prices might go up, we should expect other prices to fall commensurably and this not to be inflationary in aggregate.

Fiscal intervention is a significant risk

The government has recently announced a series of limited non-fiscal measures designed to alleviate the impact of interest rate rises on mortgage repayments.

Lenders have agreed to allow a 12-month grace period before beginning repossessions. Meanwhile, mortgage holders will also be able to extend their repayment term, or move to an interest-only plan for up to six months before moving back to their original plan without negatively affecting their credit rating.

These measures are relatively modest and do little to change the fundamentals of the economics described above. However, it is possible that as the economic pain increases, more wholesale interventions will be announced including significant mortgage holidays.

In the near term, this would provide some upside risk to our growth forecasts. But it would also boost aggregate demand and so inflationary pressure, and blunt the effectiveness of monetary policy. It would therefore require interest rates to stay higher for longer and probably eventually trigger an even deeper recession. Given the political incentives facing the government in the run up to the forthcoming general election, this is the key risk to our forecasts.

Written by Felix Feather, Quantitative Analyst at abrdn, Senior Economist Luke Bartholomew and Chief Economist Paul Diggle.

abrdn's Research Institute produces original research at the intersection of economics, policy and markets.

ii is an abrdn business.

abrdn is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.