What effect will a tougher US immigration policy have?

The Trump administration’s policies could push net migration down to levels not seen since the 1980s. This could weigh on potential growth while putting upward pressure on inflation.

4th September 2025 10:50

by Robert Gilhooly, Lizzy Galbraith and Mark Bell from Aberdeen

Key Takeaways

- The US administration’s immigration policy may impact the labour market significantly, even if its target of one million deportations annually is not reached

- The combination of increased funding for immigration enforcement, as well as evidence of a strong deterrence effect on unauthorised migration, could push net migration down to 0.75 million, a pace not seen since the 1980s. All else being equal, this could knock 0.1-0.2 percentage points (ppts) off potential growth

- In our downside scenario, in which deportations are close to administration targets and visa issuance drops more notably, potential growth is eroded by more than 0.3ppts as net migration falls to essentially zero

- However, it is unclear whether the economic cost associated with a very tight migration policy might lead to a less-aggressive policy implementation over time

- Undocumented workers make up more than 10% of the workforce in construction and agriculture, so heavily affected firms may begin to push back. As the supply of workers falls, wage differentials could entice more migrants

- The Federal Reserve has refused to be drawn on the implications for policy but will be mindful of how migration interacts with tariff-generated inflation. And, while curtailed immigration weighs on both the supply- and the demand-side of the economy, there is some evidence that migration has effectively acted as a supply pressure valve, suggesting that the net effect is to worsen supply. At a minimum, this complicates the Fed’s assessment of economic slack, such as the breakeven rate of payrolls.

Migration policies have undergone a step change

During the first six months of the Trump administration, investor attention has largely been focused on trade and fiscal policy. But, with uncertainty falling as the broad contours of US tariff policy become more settled, and Congress passing the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) fiscal package, market focus may increasingly shift to other aspects of President Donald Trump’s policy agenda.

Immigration policy in particular could have significant implications for growth, inflation, and monetary policy. After all, while on the campaign trail, Trump made clear a tough immigration policy was a core part of his agenda.

Though his pledge to deport 10 million unauthorised migrants (out of a total undocumented population of roughly 14 million) has now been reduced to a target of reaching 1 million deportations per year, this still represents a significantly more aggressive immigration policy than has been undertaken by any recent presidency, especially when combined with measures to stop border crossings.

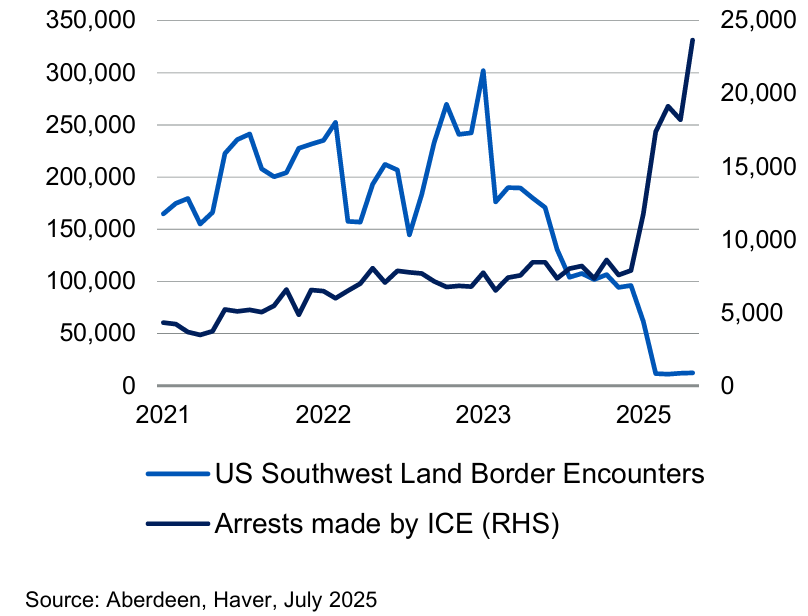

A combination of an increased troop presence on both sides of the Southern border and higher Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrest targets of 3,000 per day are already having a visible effect on enforcement activity and people flows (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: a step change in border policy is evident across encounters and arrests

Notably, ICE appears to be shifting its strategy in response to increased arrest targets from the White House and the significant drop in new arrivals at the border.

Whereas typically the bulk of arrests and deportations were conducted at the border, the majority of arrests now seems to be conducted in the US interior.

Net migration could plausibly fall to levels not seen since the 1980s

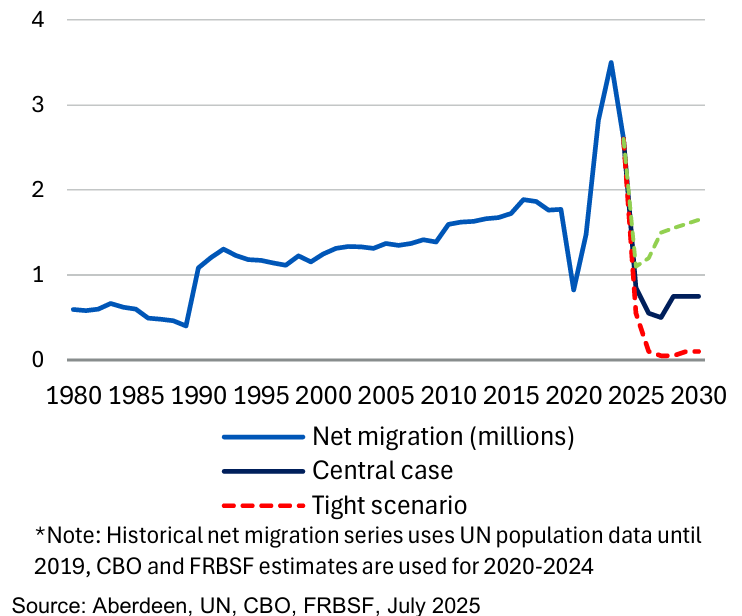

Even if the outlook for net immigration remains highly uncertain, we now expect it to settle at around 0.75 million per year. This represents a notable decrease from recent run rates and is almost as low as that last seen in the 1980s. We are revising down our best guess on the net flows of unauthorised migration, while also marginally marking down our expectations of legal migration.

But, if migration policy is more aggressive than we expect, net migration could conceivably be pushed closer to zero (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: net migration may fall well below recent rates

Much tighter immigration policy would hit the economy

It would be very hard for the US to avoid impairing potential economic growth if it severely restricts migration, particularly if expectations build that this policy is here for the long term.

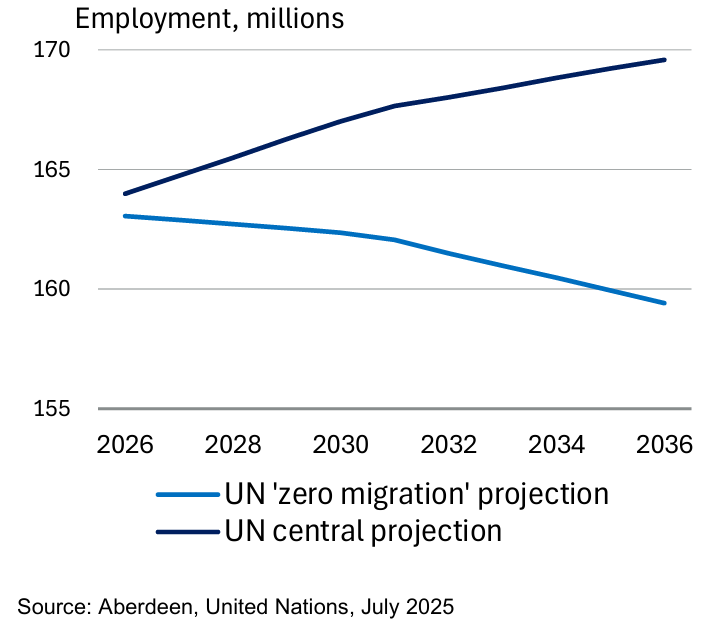

The UN World Population Prospects report provides estimates of population dynamics with net migration held at zero.

The difference over the next 50 years is stark: under the UN’s “medium fertility” scenario (with migration), the US population could rise from around 340 million now to over 400 million by 2075; under the zero-migration scenario, the US population could fall to 275 million.

The impact of a shrinking population will take time to build, but the counterfactual even in the short-term is stark.

Rather than increasing by eight million, the zero-migration scenario suggests that the prime-age population (25-54) would be unchanged over the next decade. Even allowing some rise in labour force participation across cohorts, this would translate into a stagnant employment picture over the next five years (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: the US labour force would stagnate over the next five years if net migration dropped to zero

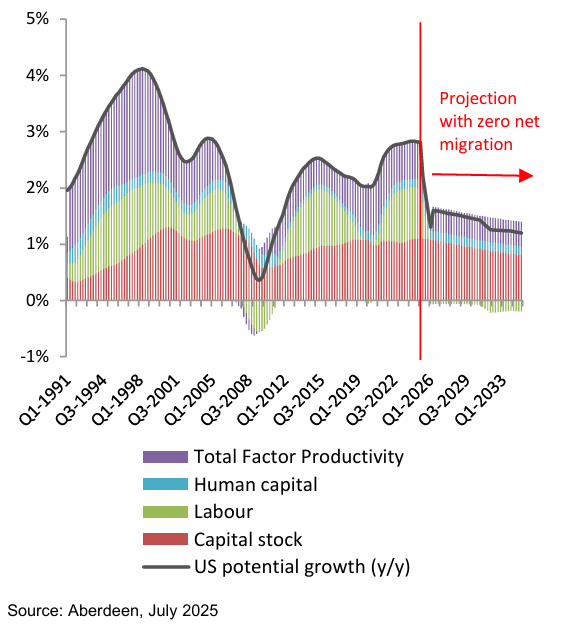

Aside from the direct effects of having fewer workers, it is plausible that a faster ageing and ultimately shrinking population would create second-round effects that damage potential growth via effects on total factor productivity and capital deepening.

Fiscal policy could become more austere as resources are diverted to proportionately rising healthcare costs; while expectations of a falling population could curtail firms’ investment as they anticipate a relatively smaller future economy, for example.

Even abstracting from the risk that an adverse feedback loop on productivity or capital deepening develops, we estimate that curtailing net migration to around zero would knock around 0.3ppts off potential growth in the US, pushing it down to around 1.5% (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: the US trend growth would be lower without migration

The Fed will be mindful of inflation implications even if it won’t explicitly say so

Over a cyclical horizon, while Federal Reserve (Fed) chair Jay Powell has thus far refused to be drawn on the potential inflationary effects of the administration’s migration policy, the central bank will need to carefully weigh the implications for demand and supply for several reasons.

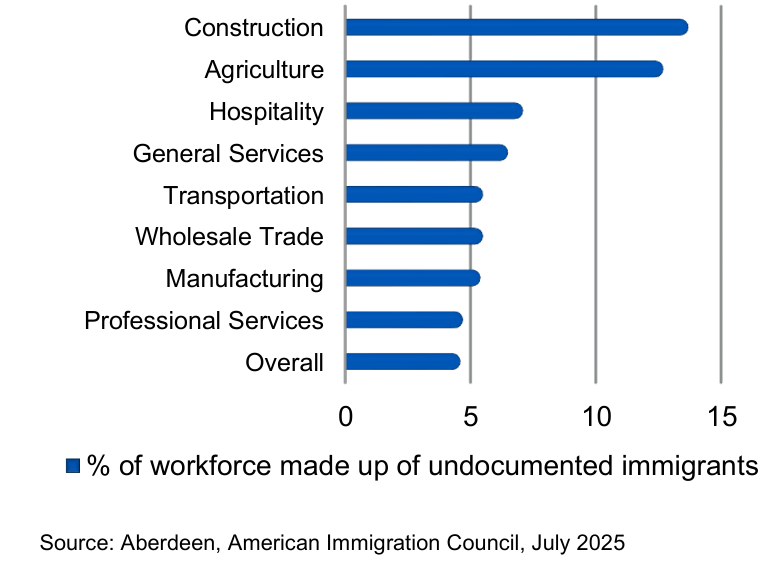

First, undocumented workers are prevalent across most sectors, but they make up more than 10% of the workforce in construction and agriculture (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: undocumented workers make up a large share of cost-sensitive industries

Arguably the timing of any shock to labour supply in cost-sensitive sectors could not be worse from the perspective of managing inflation pressures given the incoming price-level shock from higher tariffs.

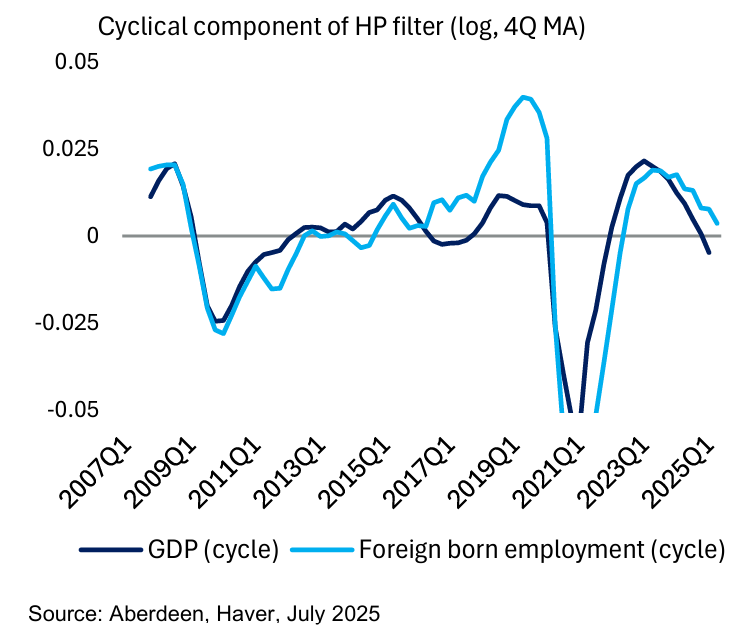

Second, sustainably curtailed migration also risks breaking a counter-cyclical pressure valve, which has made managing the US economy easier at the margin. The flow of migrants relative to trend appears to rise and fall alongside periods of stronger and weaker US growth respectively (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: migration has acted as a pressure valve, helping to contain inflationary pressure

So, when the economy is hot, migration flows pick up, which then helps to cool some of the associated inflation pressure. Without this countervailing endogenously driven positive labour supply shock, the Fed may find it more difficult to manage inflation over the long run. Or put another way, to manage the cycle, the structure of interest rates may have to be much more volatile.

Finally, in the short term, migration policy will also complicate how the Fed assesses economic slack and therefore underlying inflationary pressure. A tough migration policy pushes down on the breakeven rate of payrolls, which is the rate of job growth consistent with keeping labour market utilisation broadly unchanged month to month. We estimate this rate may fall to around 40,000 by 2027. However, it is difficult to say how fast this change will materialise.

So, in real time, it will be hard to know how much any slowdown in payroll growth is the result of weaker aggregate demand – which would necessitate a Fed policy response – or weaker labour supply – which would not necessarily require any action. As such, the Fed may struggle to respond adequately to high frequency shifts in US economic conditions, leading to potential accusations of the central bank being “behind the curve”.

Robert Gilhooly is senior emerging markets economist at Aberdeen.

Lizzy Galbraith is senior political economist at Aberdeen.

Mark Bell is graduate business analyst, global macro research at Aberdeen.

ii is an Aberdeen business.

Aberdeen is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.