Why investors keep buying shares that are bad for them

17th March 2016 08:56

by Keith Anderson from ii contributor

Ever since a seminal paper by SF Nicholson in 1960 we've known portfolios of high price/earnings (PE) 'glamour' shares underperform the market, and low PE portfolios of 'value' shares outperform.

This is known as the value-glamour split and the PE is one of the statistics you can use to exploit it. Other popular ones are price to book value, price to sales ratio, price to cash flow and dividend yield.

This split doesn't happen every year, but it is quite consistent over periods of five years or more. It averages out at about a 6% difference between the two sets of returns. The only recent five-year period when it didn't work was the run-up to the technology stock boom in 1995-2000.

Yet investors, particularly fund managers, keep on buying high PE stocks. Why do they keep on operating as if Nicholson's 1960 paper and the many papers that have built on it since had never been written?

As Warren Buffett wrote in The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville: "I can only tell you that the secret has been out for 50 years ... yet I have seen no trend toward value investing in the 35 years I've practiced it."

Putting managers first

One likely explanation first put forward in 1994 is that fund managers are thinking about their own careers rather more than the health of their clients' portfolios. Glamour shares often have high PEs precisely because they have seen a run-up in their share price lately. Shares like that are easier to justify to risk-averse clients than beaten-down value stocks.

A paper just out offers an alternative explanation, and this one applies to private investors just as much as to institutions. It is that investors see the current PE and anchor on it: they think it is a more or less permanent attribute of the stock and expect it to carry on much the same into future years.

The idea of anchoring isn't one that has been developed by finance researchers, it comes from behavioural psychology. Researchers such as Tversky and Kahneman have been investigating anchoring since the 1960s.

For example, when asked what the product of 8x7x6x5x4x3x2x1 was, people's median estimate was 2,250; but for 1x2x3x4x5x6x7x8, the median estimate was 512. People are apparently anchoring on the first numbers presented to them - the true answer is 43,320.

More worryingly, numbers that obviously give you no clue at all to the correct answer still affect it. For example, a 2008 paper by Critcher and Gilovich showed that estimates of the bill in a restaurant were affected by numbers in the restaurant's name ("Studio 97" gave higher estimates than "Studio 17").

Anchoring on high PEs

To investigate whether investors anchor on high PE's we must examine how PE's change over the years, which is no easy business. Price is one stochastic series (a random variable) but it has a lower bound of zero at which point the company is worthless. To get the PE you divide that by another stochastic series that can go negative earnings per share (EPS). We showed using formulae from option pricing theory that there is at least no reason why we would expect the prices of low PE and high PE stocks to evolve the same way. Across all plausible starting values in the formulae, value stocks ended up worth more.

To check what we can observe in the market, we got data for all US stocks from 1983 and sorted them by PE into ten buckets ('deciles'), allowing another five buckets for loss-makers. Then we calculated which bucket each stock ended up in the next year, and the returns for each of those transitions.

For every bucket, the most likely thing to happen was that the stock would be in the same bucket next year, i.e. the PE would be roughly the same. However it was almost twice as likely that a value stock would stay a value stock, as that a glamour stock would stay a glamour stock (34% vs. 18%).

Similarly, if a glamour stock stayed where it was the returns were excellent: 37% average, more than triple the 12% returns for a value stock that stayed where it was. But this reversed when we looked at the expected returns, because glamour stocks were so much more likely to end up somewhere else next year, either seeing their PE drop significantly or becoming loss-makers. The result is the typical value-glamour split, where value stocks outperform glamour stocks by about 7%.

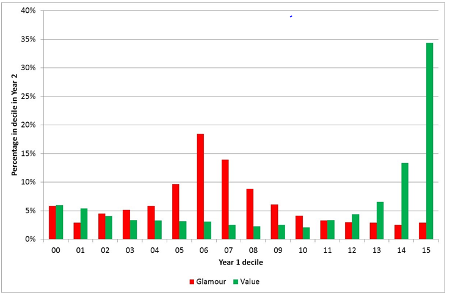

You can see how the value and glamour deciles change in the next year in the chart. Glamour shares (bucket 06) are much less likely to stay in the same bucket next year than value shares (bucket 15). In particular they are more likely to end up as loss-makers (buckets 1-5). It is the poor returns if they do so that so damage their overall expected returns.

Figure 1: Destination buckets for year 1 glamour shares (bucket 06) and value shares (bucket 15), all US stocks 1983-2010. Bucket 00 is "no PE recorded" (merged or went bankrupt) and buckets 01-05 are negative PEs.

Underestimating the evidence

Glamour investors are seriously underestimating this tendency of high PE shares to shoot off into a different PE bucket next year, by 18% if they were expecting their portfolio to do as well as the market average. The effect is particularly pronounced for small stocks suggesting it is mostly small private investors who are causing it.

However, the effect does not vary much over time. Splitting our 27 years of data into three nine-year periods and doing the calculations again showed little difference between the three. This in itself suggests a behavioural cause, as human psychology changes little over time even as the development of personal computers, then the Internet have thrown ever more data at us.

Since these are all one-year transitions, we also checked whether glamour investors with a longer time horizon could be profiting. They aren't, although over very long holding periods of 5-10 years glamour investors only did slightly worse (about 1% a year).

What we did find was that value investors are missing a trick if they only invest over one year then sell. Median returns over one year are 3-4% worse per year than holding two or three years. This could both explain why value investing is not particularly popular among institutional investors (for whom a one year holding period is a long time) and why value investors such as Warren Buffett and Ben Graham typically recommend a 2-3 year holding period.

Overall the idea that investors are suffering from a simple cognitive error is a powerful explanation for why glamour shares remain so popular. People may simply be overestimating the chances of a glamour share staying a glamour share next year, while underestimating the potential of value shares.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Keith Anderson is a Lecturer in Finance at the University of York, chairman of the Griff Fund www.griff-fund.co.uk (one of the handful of student-managed investment funds in the UK), and a private investor.

This article is based on: Anderson, K. and Zastawniak, T. (2016), Glamour, value and anchoring on the changing PE, European Journal of Finance, in press, DOI:10.1080/1351847X.2015.1113192