Will a rise in dark-pool trading impact retail investors?

Hannah Smith wades into the off-exchange trading waters to discover what they conceal - and the implicat…

18th February 2020 10:44

by Hannah Smith from interactive investor

Hannah Smith wades into the off-exchange trading waters to discover what they conceal - and the implications for investors.

So-called ‘dark pool’ trading emerged in the 1980s as a way for institutional investors to buy and sell large orders without giving away the size of their positions or distorting the market. It has probably been around even longer than that in the shape of ‘upstairs trading’ by old-school brokers.

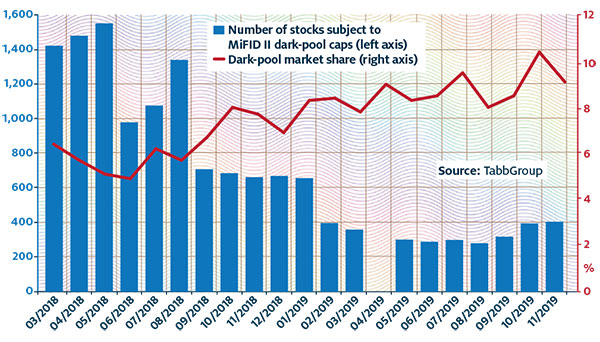

Trading activity in dark pools has reached record levels, with smaller orders now also taking place there, despite the introduction of EU rules last year designed to curb dark-pool trading. Dark pools accounted for more than 10% of European on-exchange market volume in September 2019, according to Tabb Group.

Dark-pool trading now makes up a substantial and growing part of equity market trading volumes: around 15% in the US and 8% in Europe. Combined with other types of off-exchange trading, the figures are even higher: in April 2019 the share of US stock trades executed on dark-pool and other off-market vehicles hit a one-year high of almost 39%.

But why should this matter to retail investors? What does dark-pool trading mean for asset prices, liquidity, and transparency in financial markets?

- 11 investment trusts for a £10,000 annual income

- UK share tips: six ‘value’ stocks for 2020

By trading large blocks of stock ‘in the dark’, with prices hidden from others, institutional investors can avoid the risk of other traders front-running – the unscrupulous practice of dealing based on advance knowledge of a large upcoming trade. This means pension funds and asset managers can get better prices for their end clients: retail investors such as you and I. This is the main benefit of dark pools to ordinary investors, even though they can’t access them directly.

So how do traders access dark pools? Some dark pools are operated by exchanges as a private way to trade with some of the structure of ‘lit’ (public) stock exchange trading – the London Stock Exchange runs one called Turquoise, for example. Many big investment banks, such as UBS, Credit Suisse, Barclays, Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase, also operate dark pools.

Dark pools can also be informal arrangements where buyers and sellers identify each other, either directly or through a broker. “Dark pools aim to allow people to trade in size with each other without information leaking out,” says Steve Grob, founder of capital markets consulting firm Vision57. “If you want to buy a large order of Vodafone shares, for example, you would want to do it in one go – drip-feeding orders out means people see what you are up to and the price goes up. Dark pools are not inherently bad or against the interests of retail investors.”

The use of dark pools means liquidity in the wider market is probably better than we think it is. However, it is a double-edged sword, because higher levels of off-exchange trading could reduce the liquidity found in lit exchanges, which means higher transaction costs and less efficient markets for retail investors.

Jason Escamilla, CEO and chief investment officer at US wealth manager ImpactAdvisor, plays down these concerns. He says: “I would argue that dark pools have improved the liquidity of the market and facilitated large trades without drastically moving the market around. So I don’t see dark pools as a problem in and of themselves. The point is, the retail investor is a different animal from someone who needs to move a large amount of shares in a dark pool.”

Dark-pool trading has risen sharply

Regulation target

While dark pools may bring a number of indirect advantages for retail investors, regulators have been trying to drive traders back into the light. EU regulators are worried about the lack of transparency, investor protection and the potential for conflicts of interest in dark pools. A number of dark-pool operators have been heavily fined in recent years.

A piece of EU legislation called MiFID II aims to limit the amount of trading taking place off-market and push trades back on to centralised public stock exchanges. It introduced a double volume cap that triggers a ban on dark trading when a transaction accounts for 4% of total activity in a single dark pool or 8% of total trading across the whole market. The effect of the ruling, though, has been to push investors towards other dark trading methods: over-the-counter trading surged after the new regulations came in. Grob says: “The problem is that people want to trade large blocks of stock anonymously, and they will find other ways to do that.”

Kirstie MacGillivray, head of dealing at Kames Capital, further adds: “MiFID I introduced the volume caps with the intention of driving liquidity back to the lit venues, in order to increase transparency in the marketplace and aid various types of investor. But in reality, all that has happened is that the industry has innovated around this, as most commentators predicted.”

Grob says: “MiFID II has done more damage than good because it has made trading more expensive, as more technology is needed because brokers now have to demonstrate they have achieved ‘best execution’ for their clients.”

FCA concerns

In 2016 the UK’s regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), acknowledged that users of dark pools like the extra liquidity they offer, the lower risk of information leakage, and the pricing and cost benefits. However, it noted public concern about the potential for exploitation of dark-pool users by more technologically advanced players. It said it was not concerned about price transparency “so long as dark pool activity remains relatively small versus lit markets”. But the FCA added that it wanted more to be done to identify and manage conflicts of interest.

The lack of transparency is the whole point of dark pools, but this is one reason why they are sometimes viewed with suspicion. There is more potential for investment fraud, unethical activity and market manipulation, especially where high-frequency traders find their way into dark pools. High-frequency trading uses computer algorithms to move in and out of positions in fractions of a second to amass a substantial gain from the tiny profits on each trade.

In 2016, Barclays and Credit Suisse were fined £108 million for misleading investors in their dark pools about the presence of such traders. Barclays told investors its dark pool was a safe harbour monitored for high-frequency trading, when in fact it was full of sharks – “the most aggressive and predatory high-speed traders”, according to the New York State attorney general.

Understandably, such stories can unnerve investors. However, in defence of dark pools, you can argue that all markets are potentially open to abuse by bad actors. Moreover, says Escamilla, you can’t ask traders to provide transparency before they make their trades. “It’s like saying Warren Buffett should tell us before he sells a stock. Transparency is not owed before you do a transaction.”

Another criticism levelled at dark pools is that they give institutional investors a competitive edge over other market participants. Yes, traders in dark pools have an advantage over retail investors dealing on public exchanges, but this is par for the course in investing, says Grob. He adds: “There is no evidence that dark-pool trading leads to worse outcomes for retail investors. But it is a fact of life that professional traders will always have an information advantage over retail investors – it is the way of the world.”

Future picture

Kames Capital’s chief investment officer, Stephen Jones, says about a third of the firm’s equity trades take place in dark pools. In his view, the next thing to watch out for will be whether bonds begin to be traded there too as technology advances, something he suggests could “revolutionise” financial markets.

Currently, most bonds are traded over the counter – meaning the trade is done directly between two parties, often via a broker-dealer – rather than on public exchanges. This is because there are many more types of bonds than there are equities with different characteristics, and it is harder to list their current prices because they are affected by variables such as interest rates and credit ratings.

Another important theme will be the continuing influence of high-frequency traders. While some firms such as Virtu Financial and Jump Trading specialise in high-frequency trading, many hedge funds and investment banks also commonly use this strategy. Their increasing presence in dark pools could spell trouble for investors trying to trade large positions, because their presence tends to increase volatility – they are thought to have contributed to the Flash Crash in May 2010 by suddenly stifling market liquidity.

Dark pools allow the biggest investors to deal large blocks of shares without showing their hand, and this is vital to the functioning of healthy capital markets and is good for retail investors. But, as trading volumes grow, investors may continue to face pressure from regulators uneasy about what goes on in these murky waters.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.