Is value investing a broken model?

Value has lagged returns from growth investing for the past decade. We discuss when the tide will turn.

20th February 2019 10:23

by Tom Bailey from interactive investor

Value has lagged returns from growth investing for the past decade. We discuss when the tide will turn.

The concept of value investing is pretty straightforward. Value investors look for shares that are selling for less than they deem them to be really worth. The hope is that the market will eventually catch up, resulting in the 'intrinsic value' of a company and its market value converging, enabling investors to profit from the revalued share's price increase.

The problem, however, is that this style of investing has not worked particularly well over the past decade. Instead, growth investing – where investors place less emphasis on the price they are paying for a company than on its earnings growth prospects – has won the day.

Golden decade for growth

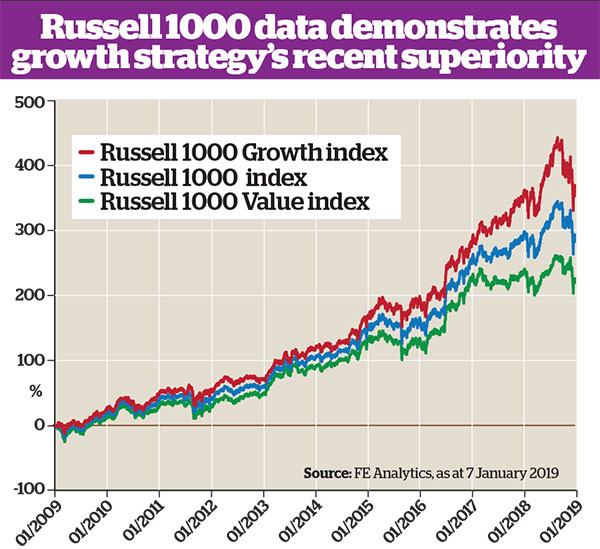

To underline the point, it is helpful to make some comparisons. The Russell 100 Value index is composed of the 1,000 largest US companies deemed to be 'value' stocks, as measured by their price-to-book ratios. If at the start of 2009, you had invested £100 in the index, the value of your investment today, 10 years later, would stand at roughly £300, a return of 200% (excluding fees and other costs).

On the surface, such a return should make you happy. However, if you were to compare that return with the return you might have achieved in other indices over the same period, you would probably feel disappointed.

For instance, had you invested the same amount in the broader Russell 1000 index over that decade, your £100 would have turned into about £365, a return of 265%. What's more, if you had anticipated the popularity of growth stocks over the decade and invested your £100 in the Russell 1000 Growth index, your investment would have been worth £447 – a 347% return.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance

Investing in value shares has been a recipe for underperformance over the past decade, but this has not always been the case. Equity records show that value has underperformed growth for a sustained period only twice before: during the Great Depression of the 1930s and the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s.

The reasons given for value's recent underperformance, however, appear logical: economic and financial conditions have been more conducive to strong performance by growth stocks.

The slowness of the economic recovery that followed the 2007/08 financial crisis has meant that the usual rebound in corporate earnings, which results in good performance for value stocks, has also been slow. At the same time, low interest rates have made high-value growth stocks more attractive, as the expected future earnings of growth companies measured against the cost of borrowing have looked more attractive. A proliferation of share buybacks has added to growth stock momentum.

However, these conditions may now be weakening, and many investors expect the value investing strategy's historic outperformance to return. According to Thomas Becket, investment manager at Psigma, last year we probably reached an inflection point in the growth versus value story. However, as Becket notes, over the past decade there has been a number of false dawns for value investing.

The strategy's poor performance has led some to start doubting the underlying fundamentals of value investing. Alex Neilson, investment manager at Investec, says: "Understandably, investors are asking when or if value will start to outperform."

The new economy

Value investing is all about attempting to find shares trading at below their supposed intrinsic value. While there are many ways of determining intrinsic value, comparing the so-called book value of a company with its market price (the price-to-book ratio) has long been a staple measure of value.

The book value factors in all of a company’s assets – such as stocks, bonds, inventory, manufacturing equipment and property – as stated on its balance sheet. On the basis of this value, investors determine the price-to-book by dividing market price per share by book value per share.

A low price-to-book ratio suggests a stock is undervalued and therefore cheap. As noted, this is how the Russell 1000 index defines value. Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN), which is considered a growth stock, and certainly not a value stock, has a relatively high price-to-book ratio of 19.7 (as of early January 2019). Meanwhile, JPMorgan Chase, the largest constituent of the Russell 2000 Value index, has a price-to-book ratio of just 1.49. Any company with a price-to-book ratio of less than 3 is generally considered cheap, while a firm with a price-to-book ratio of under 1 is selling for less than the value of the assets listed on its balance sheet.

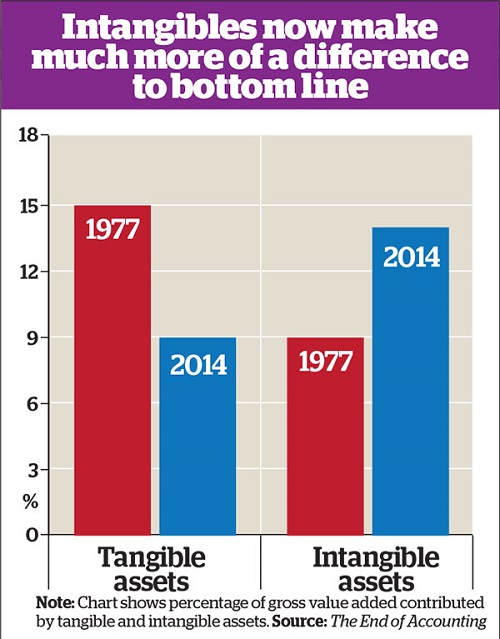

However, a growing chorus of voices has started to argue that this established measure of value has become less useful as intangible assets have started to play a larger role in the economy. The most forceful advocates of this idea are academics Baruch Lev and Feng Gu, whose thesis is laid out in their book, The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors and Managers.

In the past firms relied on plant equipment and machinery to create products, but in the 21st century, intangibles such as intellectual property (in the form of software, branding or patents) and the organisational structure of labour-intensive service jobs are becoming increasingly important.

The two academics argue that accounting principles for company balance sheets have not kept up with this change. For example, under conventional accounting principles, when a company invest in patents or brand development, the associated costs are treated as an expense on the balance sheet, rather than an asset. As a result, the balance sheets (or book values) of firms fail to provide the accurate figures needed to determine the intrinsic value of a company. Price-to-book ratios, Lev and Gu argue, are no longer a useful way to look at the intrinsic value of a company.

Money managers have started to pick up on this argument. Bill Nygren, chief investment officer at Harris Associates, speaking at a Natixis Asset Management conference in 2018, said: "The balance sheet isn't what it used to be, as we've moved from an asset-heavy to an asset-light economy." The tie between share price and tangible book value has been broken, Nygren says. He points out that in 1975 there was a 71% correlation between book value and stock price for companies listed on the S&P 500 index. Today that is down to 14%.

He adds:

"What's really valuable in the modern economy is not so much plant and machines, it's intellectual capital and other assets. Value investors who only look at tangible book value have been going through a really difficult period."

What has this meant for value investing over the past decade? Feng says: "Value investing requires you to take a short position on growth stocks and a long position on firms with a low price-to-book ratios. Over the past 10 years, however, growth firms didn't actually lose market value, but instead continued gaining value, because their actual value [in the form of intangible assets] was understated."

Does this mean the value investing model is broken? Price-to-book measures of value may be less useful than they used to be, but the premise of value investing itself is not necessarily defunct.

The end of value?

Patrick Thomas, an investment manager at Canaccord Genuity Wealth Management, says:

"Value investing has a fluid definition. [Valuefocused fund] managers such as Nick Kirrage, Alistair Mundy and Alex Wright all fish in similar ponds, yet they have very different criteria for what they will and will not own."

Nrygen points out that value investing involves more than just picking through price-to-book ratios. Investors, he says, "still get emotional and follow fads, and when that happens, value and price diverge". As always, certain stocks are excessively punished by markets. Price still decouples from intrinsic value, so an investor can still buy a stock cheaply. "The difference today," he adds, "is that the focus is much more on earnings than book value, and earnings need to be adjusted for intangibles."

Feng, however, believes value investing metrics remain fraught with problems. Many value investors look at price-to-earnings ratios. But earnings, says Feng, are also affected by the rise of intangibles. "Net income is subject to the same bias," as value-creating intangibles are also often not treated as assets.

With the rise of intangibles, Feng argues, investors should be looking at the individual "strategic resources" of each company to better determine its intrinsic worth. This alone, however, would make comparative valuations – and therefore the determination of which stocks are ‘cheap’ relative to others – almost impossible. Price-to-book and price-to-earnings approaches both rely on an ability to measure one firm against others in the market.

Against this perspective, not all investors think much has changed in reality. Becket notes that while intangibles have created distortions on the balance sheets of US companies, value has simply been out of fashion.

Becket is anticipating a return to value investment outperformance, particularly in Asia. He points out that Asian indices tend to be made up of more traditional, tangible asset-heavy companies – the sort of companies where value investing has traditionally worked best.

How one fund manager is responding to the age of intangibles

Like Feng, Lucy Macdonald, manager of Brunner trust, advocates looking closer at companies' internal workings, albeit without discarding the traditional comparative metrics of equity investors.

She says: "From an investor's point of view, we should be requesting information from companies on digital assets and resources; assessing relevant metrics for each industry, whether that is churn, sales per employee or sales momentum; and analysing how effective the business model appears to be."

Ultimately, however, she says, accounting rules will need to be implemented.

"Lobbying for better accounting of the digital world makes sense. This has to occur over time if financial statements are to remain relevant."

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.