Why bigger is not always better for your investment fund

7th September 2018 12:16

by Cherry Reynard from interactive investor

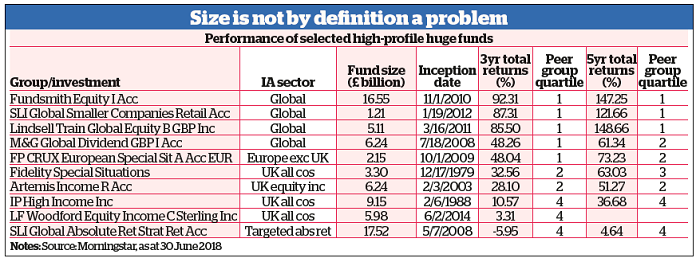

How does the size of a fund impact on its performance? At what point does size start to matter? Are certain investment styles and types more susceptible to shrinking returns? Cherry Reynard reports.

Fund management companies have an inherent conflict of interest, though few like to admit it. The sales teams and shareholders want them to grow funds as large as possible, because that creates higher fees and delivers higher profits. However, it is clear that this is not always in the interests of those who invest in their funds. There are too many examples of funds that have grown very large, only to see performance slip, to write it off as coincidence.

The correlation is hard to prove, but there are plenty of anecdotal examples. Standard Life Investment's GARS fund has been among the most high-profile examples, with assets under management of £26.8 billion at its peak in May 2016. However, it has steadily been losing assets as performance has waned. The managers insist that size is not a contributory factor – and certainly the group has seen some turnover of its fund management team as well, and its style has been out of favour; but many believe that the sheer volume of assets has made it more difficult for the group to manage these other issues.

There are other examples. The M&G Recovery fund gathered significant assets on the back of strong performance, only to see that strong performance evaporate. Yes, it has not been a favourable market for manager Tom Dobell, and his 'value' style has been under pressure – but other value managers have not struggled in the same way, and once again weight of assets appears to have hindered the fund’s ability to deal with a changing market environment.

There are more extreme examples. Larger funds raise the profile of a manager and bring additional pressures. The defence lawyer of former BlackRock UK Absolute Alpha fund manager Mark Lyttleton, jailed in 2016 for insider dealing, said the illegal trades were made when Lyttleton was 'a man in mental free-fall', under pressure in his job after his funds had grown very quickly and then begun underperforming.

Very small funds a problem

It should be noted that very small funds are also a problem. They lack scale and therefore have higher expenses, which gives the manager a performance hurdle to overcome. However, the difference is that investors tend to recognise that they have taken a risk on a new fund. With very large funds, investors may be reassured by the experience of the manager and the fact that he is popular with investors.

Gary Potter, co-head of the BMO GAM multi-manager team, says:

"We have 16 key factors we consider when buying funds. Of these, capacity is the bell that rings the loudest. However good the ship's captain, it's very difficult to move a super-tanker around. Getting into the nooks and crannies of the stockmarket is often critical to long-term success – this is the antithesis of what happens at a large fund."

Yet there are fund managers who seem to be able to handle huge funds. Adrian Frost has continued to deliver solid, if unexciting, performance from the £6.2 billion Artemis Income fund. At the same time, Neil Woodford's performance, both good and bad, seems to have been unaffected by the size of his funds. He ran a lot of money very successfully in larger funds. He simply made decisions that were good. More recently, he has made decisions that appear to be less good. As such, while the (in)ability to sell things may well be a factor, if a manager doesn't like, say, mining stocks, and they go up, that is not a reflection of the size of the fund.

Are skills used better in smaller funds?

Another question here is perhaps not whether good managers can handle the large funds they've been given, but whether their skill would be used to better effect on smaller funds. In this case, investors may spend their time more productively trying to find the next Woodford or Frost, rather than doggedly sticking with the existing ringleader.

Why does it make a difference? Take an example where a manager has a £10 billion fund. Because there are a limited number of companies that can support large single investments, the number of companies in the portfolio may have to increase, diminishing the impact of the managers' skill. Equally, they may be limited to the top half of the FTSE 250 index plus the blue-chips of the FTSE 100. That's fine if they've made their name in skilled selection of large caps, but if people are buying them for their strength in picking smaller companies, that may not be what they’re getting.

John Husselbee, head of multi-asset at Liontrust Asset Management, says:

"We find that after a certain point, a fund will start reverting to the mean and become more of an index tracker than an active fund."

There is also the problem that larger companies are well-covered by investment analysts and may not offer the same scope for stock-picking.

How fund size can make a difference

With this in mind, the extent to which fund size makes a difference will depend on a number of factors. First is the assets in which the fund invests. It is more difficult to manage large funds in sectors such as emerging markets, or smaller companies, or niche areas of the bond market. When Jupiter decided to launch an emerging and frontier markets income fund for Ross Teverson, it chose to structure it as an investment trust (see below), to ensure that it retained the ability to invest in the small, shallow markets of countries such as those in Africa.

Potter says it will also depend on what other assets the manager runs alongside the fund in question. He adds:

"A manager might be running a £250 million portfolio but then have £7-8 billion in institutional mandates. Some managers also run money on an outsourced basis for multi-manager groups. It’s not the size of the funds, but the size of the assets."

He also believes capacity limits should be reviewed if any team member leaves.

Source: interactive investor Past performance is not a guide to future performance

It is also important to look at incentives, observes Husselbee. He says he has encountered funds where the manager is incentivised to run as large a fund as possible and then gradually moves into lower-risk assets in order to preserve the size of the fund. Again, investors don't get what they think they're getting. Husselbee adds that fund managers have got smarter on incentives today and he doesn't see this situation as often. However, it still happens from time to time, particularly with hedge funds.

Peter Elston, chief investment officer of Seneca Investment Managers, says he prefers smaller funds in general, but considers each fund on a case-by-case basis. He adds: "Smaller funds are more nimble and able to invest in small and mid-cap companies. The performance of mid-cap companies is much better over 20-30 years. This is about potential to grow. The market consistently underestimates the extent to which mid-cap companies can outperform."

He also likes small funds that have just been established, particularly if they are run by experienced managers:

"They have to work really hard in these early years to prove themselves on their own. It tends to mean funds do well in the early period."

This chimes with the view of Stephen Peters, multi-manager at Barclays Investment Solutions, who says: "For most strategies, you would prefer less rather than more money. In an ideal world, you want a small fund that is benefiting from growing assets. Any extra money goes into new ideas, which then takes the prices up, which then improves performance – a virtuous circle. When this reverses, however - if a key fund manager leaves, for example - it can be a difficult period for the fund."

This is particularly true for over-the-counter markets such as corporate bonds. When a fund manager has a large fund which is seeing inflows, he is in a position to drive a hard bargain on pricing. However, if those flows reverse, he may be forced to liquidate large positions, making him a forced seller and vulnerable on pricing. Husselbee says: "It stands to reason that a fund that is having positive subscriptions is a lot easier to manage than one having redemptions."

How, then, can the conflict at the heart of asset management companies be resolved? The social purpose of the industry is to allocate capital efficiently and make clients wealthier, not to give the sales and marketing teams something to do. However, too often, that's the way fund management groups appear to be run: the answer is always to gather more assets rather than fire the sales guy.

Private companies have more leeway than public companies. Private owners can decide to turn off the taps when it jeopardises the long-term reputation of the company. Public companies, with shareholder expectations and analyst targets hanging over them, do not have the same freedom. They too may occasionally turn off the taps, but it is more difficult for them to go against corporate interests.

Capping funds is another solution that has been used by fund groups. JO Hambro, for example, has long placed capacity limits on its funds. Other groups – Majedie and Miton among them – also limit capacity. This is not an exact science. Some will simply stop marketing the fund but allow existing investors to reinvest. Others stop new inflows altogether. There are often hard and soft limits.

Potter warns that investors need to be wary of 'capacity creep'. One year a manager will say he can only manage £1 billion. The next year it has crept up to £1.5 billion and then to £2 billion or £3 billion. Managers who seek to be represented within model portfolios on platforms or from discretionary fund managers cannot set capacity limits, because it is almost impossible to turn off those taps once they are open, and this is another issue for private investors to bear in mind.

Absence of differential pricing

Peters is surprised that there hasn’t yet been any differential pricing in the industry: "The very best managers should justify a premium price versus the rest - and probably run a smaller, more manageable amount of money. It is interesting that there is little price discrimination in the open-ended fund market - most cluster in the 0.6-0.9% mark. Why is that? Is it that the market cannot identify "the very best", or that the very best doesn't exist because performance generally reverts to the benchmark over the long term and any "skill" is actually just a style or size bias?"

This latter point is probably an argument for another day, but it's true that if there were more discrimination between good funds and bad funds, good fund managers might not have to keep raising more assets because they could charge a higher price and some of the conflict would evaporate. Of course, they could also accept a lower income – and given their starting point, that might not be a bad thing.

There are no hard and fast rules on fund size. However, it is undoubtedly true that if they raise a lot of assets, and particularly if those assets are raised very quickly, fund managers can find it difficult to sustain the performance that may have attracted those investors in the first place. Investors need to exercise caution.

Investment trust capacity controls

Investment trusts have some inherent capacity controls. With an investment trust, the manager goes to the market to raise a set amount of capital. That capital is then fixed, and if the manager believes he can manage more money, he will have to go back to the market to get some. This is very different from open-ended funds where the capacity is, in theory at least, limitless – if people want to buy the fund, the manager can keep creating more units.

It is theoretically possible, however, that fund growth will push trusts over the edge, and a number of trusts have taken steps to cap their capacity. Anthony Leatham, investment companies analyst at Peel Hunt, gives the example of the River & Mercantile Micro-cap Growth fund: "They are managing at the smaller end of the small cap market and decided they could only manage a certain amount. As such, they put in place a mechanism whereby if assets grew larger than £100 million, they would have compulsory redemption of the shares. This means shareholders would be forced to sell part of their holdings." Gervais Williams has also said that he will limit his Miton UK Microcap fund to £250 million.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.