Is global bond market sell-off a golden opportunity?

Following recent events in global bond markets and a jump in yields on offer, analyst John Ficenec studies the logic behind owning UK government debt.

11th September 2025 13:09

by John Ficenec from interactive investor

With yields on government debt soaring across the world and fears of a black hole swallowing the UK finances, the atmosphere in fixed-income markets is febrile to say the least.

- Invest with ii: Investing in Bonds | Free Regular Investing | Open a SIPP

But for the long-term investor it looks like the opportunity of a lifetime has just presented itself in holding UK long-term gilts, and there are plenty of ways to take advantage.

UK borrowing hits record high

The cost of borrowing on long-term 30-year UK gilts hit a high of 5.7% last week, which is the highest level since 1998. This has stoked fears that we are seeing the early stages of a sell-off in UK debt, which could lead to a full-on currency crisis. With a date for the Autumn Budget now set at 26 November there are also questions of how sustainable our government borrowing levels are and how we are going to stay on track to pay it back.

Compelling returns on offer

UK gilts stabilised somewhat into the end of last week with the 30-year gilt ending at 5.5%, having peaked at around 5.7%, but it’s that return that should have long-term investors looking twice. Let’s not forget that a gilt is classed as a zero-risk investment, pretty much the safest thing you can hold other than putting it in a bank.

- Everything you need to know about investing in gilts

- Sign up to our free newsletter for investment ideas, latest news and award-winning analysis

You could even argue it’s safer than a bank as your bank deposits are protected only up to £85,000, whereas to lose your money on gilts the entire UK would have to default on its debts. If that happens, you’ll have bigger things to worry about.

Just putting that current 5.5% gilt yield in perspective, the FTSE 100 has returned 4.1% annualised with dividends reinvested since 2000, according to figures from IFA Magazine, and the best one-year cash ISA is about 4.3%.

In the US, while the S&P 500 has average annualised returns of around 10% since 1927, more recently that has fallen to around 6% since 2000. Given the concentration of the US index in just a handful of technology stocks, its sluggish growth and esoteric political backdrop, it’s a fair assumption that future returns would be closer to the 6% rather than 10%.

The total return on your 30-year UK gilts compounds to over 270%, making every £1,000 invested worth £2,700 at maturity, those types of returns with such low risk are not to be sniffed at.

Don’t panic, don’t panic

At the risk of sounding like Dad’s Army’s Corporal Jones, while UK gilt yields are under pressure there are a number of reasons why I don’t think its cause for panic just yet. What’s more, once understood, investors can make a more informed decision about whether they’d like to invest.

The yield on government debt is a function of its market price and the fixed coupon it pays, so when the 30-year gilt is issued by the Debt Management Office (DMO) at par, or £100, with a fixed coupon or interest payment of 4.4%, if that gilt is sold for a lower price in the secondary market as is happening now, for say £83, then the coupon is still 4.4%, but the implied yield has risen to 5.3%, and you also benefit from the capital appreciation of purchasing the bond at £83 and redeeming it in 30 years at £100. So, altogether your annualised return, or yield to maturity, is around 5.6%.

It’s clear why inflation causes gilts to sell off. If inflation rises to 4%, as it’s expected to in the UK in September, then your real return of gilt yield less inflation is eaten away, so they become a less attractive option.

UK inflation rates are some of the highest in Europe and have been described as “sticky” for their persistence. That shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise though because high inflation is largely self-inflicted.

- Retirement case study: how I manage a £2.5m SIPP and ISA portfolio

- Benstead on Bonds: are long gilts at 5.5% a no-brainer?

The UK is an island and as such imports most of the goods and services it needs, we also introduced an additional layer of cost inflation and bureaucracy leaving our largest trading partner via Brexit, which has now been further exacerbated by US President Donald Trump’s tariffs. Add into the mix privatising our water, energy and utilities and we have some of the highest energy prices in Europe despite the second-largest oil and gas reserves. With wages seeking to match these pressures, inflation has indeed proved “sticky” to say the least.

But there is reason for optimism on the inflation front. The cost of living is tipped to fall to 3.3% in the final three months of 2025, according to Treasury forecasts, before falling further to end next year at around 2%. This is not just wishful thinking; oil prices have fallen to around $65 a barrel from around $80 a barrel at the start of the year, and the Opec+ group of producing nations have pledged to increase output in October. Wage inflation was running hot at around 6% at the start of the year but is forecast to cool to 3.7% by the end of this year, according to Bank of England forecasts.

Super-massive black holes

The problem with black holes is fear of the unknown. Henry David Thoreau documented a similar problem when locals told him that the Walden pond he lived next to was bottomless. He set about disproving this with a boat, line and weight, finding that the pond was only 30 metres deep at its greatest depth and dispelling the fears. So, how big is the UK’s black hole?

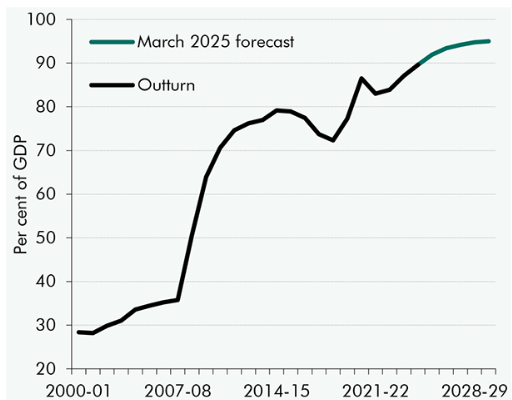

We have to go back a bit to understand where we are. In 2008, UK public sector debt to GDP was a very respectable 35%; then we had the banking crisis and bailing out the banks when combined with the quantitative easing necessary to get the economy going again cost around £650 billion and left us with debt to GDP of 80% by 2015.

Sorting out the Covid pandemic cost another £310 billion, taking debt to GDP to over 90% by 2022. And it has remained at these elevated levels, with debt to GDP of 96.1% at the end of July. But we are not alone, and we’re certainly not an outlier.

The rise of public sector net debt to GDP since 2000

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility.

The US public sector debt to GDP was 120% at the end of June, across Europe borrowing is also high with Greece at 153%, Italy 138%, France 114%, Belgium 107%, Spain 104%, and Portugal 96.4%. The wider Euro area average is 88%. Against this backdrop we certainly don’t stand out at 96.1%.

One way of looking at it is that to solve past crises we’ve pulled forward future growth, and successive governments have kicked the can down the road in terms of paying that back. Now we’re rapidly approaching the point at which the piper has to be paid, which is causing friction between labour markets and corporations that the current government is trying to resolve. The French government is facing its own vote of no confidence as it tries to pass a bill to reduce spending.

So, the black hole itself isn’t any worse, or noticeably worse than elsewhere, the issue we do have is its rate of increase. Labour’s fiscal rules demand we aren’t spending more than we receive by 2030. Labour tried to cut spending with the welfare reform bill, but this was rejected by MPs, so with spending staying the same and absent a growth spurt, then taxes will have to rise to tackle the deficit. In this respect the Autumn Budget becomes critical.

But, again, there are signs of hope, and the debt is manageable as long as the UK economy keeps growing. Since the end of 2023, annualised GDP growth has been 1.8%, and while it is forecast to fall to 1% this year, a swift recovery to 1.9% is expected in 2026, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

Back to basis

Trading by hedge funds is also putting additional stress on long-term UK gilt yields. Funds are taking investment positions to profit from the rising yields in a number of different ways. The first is called a curve steepener, which anticipates that if inflation remains high, then long-term yields will sell off more than short-term yields as investors move along the curve into short-term debt. The second is a basis trade, which exploits differences between the cash gilt and derivatives priced from that gilt, like futures. Importantly, these aren’t directional trades betting against UK gilts, rather it aims to profit from inefficiency in the market.

- Pension tax-free cash: do you have a plan for yours?

- Bond Watch: what ‘vulnerable’ UK finances mean for gilts

The key element about these trades is that they are looking to exploit small moves in the basis points of UK gilts, or one-hundredth of a percentage point, so to make them profitable for hedge funds the leverage used is sometimes over 50 times. So nominally, yes, there may be positions of hundreds of millions shorting UK 10-year gilts, but equally there are positions of hundreds of millions buying UK 2-year gilts. This is not a vote of confidence in the UK or government policy, it’s easy to see how a few funds all targeting the same position could exacerbate an already weak gilts market. The latest analysis has shown that over 60% of the UK gilt market volume in January and February of this year was from hedge funds, up from 50% two years ago.

The UK long-term gilts market is already soft this year for a number of reasons. There is still a requirement for the Debt Management Office to issue huge amounts of paper to fund spending, but as the Bank of England is in a quantitative tightening phase there is less demand for gilts. Also, the demand from long-term investors like defined benefit (DB) pension funds is falling, with the number of DB schemes down to 4,974 at the end of last year from, 7,751 in 2006, with members also down sharply to 8.8 million from 14 million over the same time period.

Against an already weak market it’s easy to see how the hedge funds have spotted an opportunity to take advantage and make a quick profit. What is important though is that they aren’t betting against the market, merely the structural demand and supply imbalances within it. Sterling itself is not weak.

Fears of a currency crisis

There appears to be a media fixation with black holes at the moment, and to draw the conclusion that a higher long-term gilt yield is a vote of no confidence in the UK and the chancellor at the moment is a prime example of narrative fallacy - one doesn’t follow the other.

Yes, gilt yields are high, but they are high for a number of very clear reasons based on economic fundamentals, not that the UK is going to collapse. We have high inflation, low growth, high debt issuance and weak long-term gilt demand all exacerbated by short-term trading. 30-year UK gilts have already been around 5.5% several times this year in January, April, May, and July, yet nobody was calling it a vote of no confidence then.

Looking at sterling, the UK currency is actually getting stronger. The pound is trading at around 1.35 to the dollar at the moment, up from 1.25 at the start of this year and 1.31 a year ago. It’s also significantly higher than the 1.16 three years ago around the time of Liz Truss’s mini-budget, and near the top of the range it has traded since we voted to leave the European Union on 23 June 2016, with sterling at 1.45. So, we’re certainly not in any currency crisis scenario.

Pound to US dollar since September 2016

Source: TradingView. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

We’re also not close to any 1976 currency crisis, which was caused by 15% inflation, with the cost of living slightly elevated and set to fall sharply; likewise, the Black Wednesday crisis of 1992 was caused by joining a strict currency peg with UK inflation too high and the currency overvalued, none of which are true today.

Risk and long-term gilts

There are objections to owning long-dated gilts, especially with yields on UK debt spiking, meaning we’re having to pay a lot more on our £2.9 trillion total UK debt pile.

The fear is that we get sucked into a “doom loop” where we have to cut spending and increase taxes, which further reduces growth, just to pay the interest on the debt with no hope of ever paying it back.

However, I believe those fears look overcooked. The deficit is forecast to fall to around £74 billion by the end of 2030, but here is the important part, if you adjust for what is spent on road, rail and other infrastructure, which seems fair, then we get a surplus of £9.9 billion by 2030, or the much-heralded headroom, according to latest OBR figures.

And two recent heavily oversubscribed debt auctions suggest the market is quite happy with these forecasts. The yield on UK 2-year and 5-year gilts has fallen this year, 10-year gilts are flat, and only long-dated 30-year gilts have really suffered.

The biggy is duration risk, with master investor Warren Buffett famously refusing to even touch long-term paper after getting his fingers burnt. By duration risk we mean the risk prices fall further before the maturity date, during which time you have to realise losses before it recovers.

Admittedly, while very few retail investors have a 30-year horizon, it all comes down to what’s in the price, and with long-term yields already at extremes not seen since 1998, then it’s your appetite for how much further they could fall that would be too painful, opposed to the potential for steady returns.

Fortune favours the brave

So, for investors this could be the time to screw their courage to the sticking place. UK long-term gilts look very attractive for the long-term investor. These types of returns, higher than a cash ISA in one of the lowest risk investments out there don’t come around often, and in a balanced portfolio could prove a real driving force for returns.

While long-term investors are currently outnumbered by those betting against gilts, eventually the short-term returns on offer will fade, hedge funds will begin exiting the trade, and yields will recover, as was already happening at the end of last week.

Some ideas for long-terms gilts of around 30 years are available such as 4¼% Treasury Gilt 2055 (LSE:TR4Q); UNITED KINGDOM 4.375 31/07/2054 (LSE:T54); UNITED KINGDOM 3.75 22/10/2053 (LSE:T53); UNITED KINGDOM 3.75 22/07/2052 (LSE:T52) or the 10-year Treasury (UNITED KINGDOM 4.5 07/03/2035 (LSE:T35)), 4½% Treasury Gilt 2034 (LSE:TR34).

For those looking at what this means for equities, there is certainly no need to fear a Black Wednesday-type scenario. The UK private sector is in a good position, excluding the Covid furlough blip and UK household savings are at some of their highest levels since 1996. Banks are also well capitalised and highly profitable with share prices near their highest since 2008, and corporate balance sheets are robust.

Looking at the wider picture, it still looks like conditions are set for strong returns in the FTSE 250 and mid-cap region of the market as the FTSE 100 will suffer drag from a strong pound and weaker commodity prices.

John Ficenec is a freelance contributor and not a direct employee of interactive investor.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.