Is a million pounds enough to retire on?

Will your pension and investments keep you in the style to which you have become accustomed?

4th November 2019 11:16

by Moira O'Neill from interactive investor

Will your pension and investments keep you in the style to which you have become accustomed? interactive investor's head of personal finance Moira O'Neill investigates.

A surprising question from my nine-year-old daughter: how much money do you need to stop working?

I pluck the figure of £1 million out of the air. It's a nice round number and one that she understands as "ginormous" so immediately stops her wishful thoughts of more Mummy school pick-ups.

It is also conveniently close to the lifetime allowance of £1.055 million that an individual can save into a pension before tax charges apply. That said, I would invest this sum in a neatly tax-efficient combination of a pension and stocks and shares ISA so I could take income flexibly and earlier than the age of 55 if I needed to. But I am in danger of turning this into a boring bedtime story.

- Learn more: SIPP Portfolio Ideas | How SIPPs Work | Transfer a SIPP

After she falls asleep, I am left with the question of whether saving £1 million is achievable. For me - and for most of the country - aiming for a retirement pot of this size feels like a fantasy. Like many FT readers, I'm lucky enough to earn much more than the average UK wage of about £27,000 per year. But even higher earners are seeing their potential retirement savings squeezed by the struggle to get on the property ladder or the size of their monthly mortgage repayments when they do.

A further question that may well be keeping you awake . . . is £1 million even enough to retire on, or is there still a risk of running out?

Balancing act

In the past few weeks, there has been a confluence of gloomy surveys warning British workers about the inadequacy of their pensions savings.

While final salary or defined benefit pensions provide a steady income throughout later life, workers saving into defined contribution (DC) pension plans should by now be painfully aware that the risk of saving enough for their future retirement rests on them.

In short, we need to to be realistic about money milestones. Will we really need to hit that £1 million target?

Since 2015, pension freedoms have allowed more income flexibility in retirement and there is growing evidence that this has changed our attitudes towards when we stop work - or if we will at all.

One key finding from Interactive Investor's Great British Retirement survey, exploring the attitudes and experiences of 10,000 Brits approaching or in retirement, was that more than half of respondents aspire not to retire. Some 52% planned to keep working into retirement, either part-time or through self-employment.

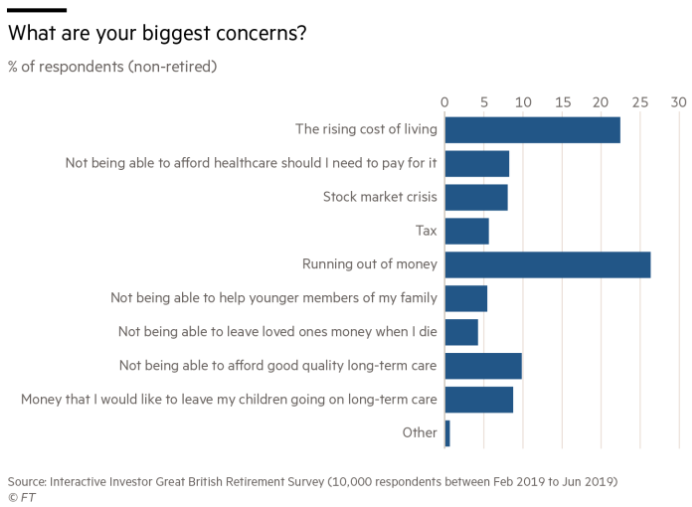

Of the respondents who said they intended to continue working for pleasure rather than financial need, twice as many men as women were in this category. However, almost two-thirds of respondents disagreed that retirement was a time of pleasure. Financial worries loom large.

The three top objectives in retirement were peace of mind, not running out of money, and having enough money to leave behind to children. And the biggest financial regret? Not starting a pension sooner.

Striking this financial balance between our present and future selves is difficult. I hate the idea of cutting back on family holidays so that my future self can afford a luxury round-the-world trip in 2040. But nor do I want to eat out today, only to spend my retirement subsisting on baked beans.

Nevertheless, if today's 50p can of beans ends up costing 90p by 2040, I'll be grateful for an unintended financial surplus. Plus, I won't mind having something left over to pass on to the next generation - only 3% of respondents to the survey said they regretted helping their children financially.

How much is enough?

Returning to the question of how much is enough - the answer depends on your retirement aspirations.

For the first four scenarios below, I've calculated the lump sum needed to achieve this level of income via investing.

I've modelled this on what I think is a conservative and sustainable annual withdrawal rate of 3% - low enough that you're unlikely to run out of money in your lifetime, whether you need an income for 30 or even 50 years. I have assumed that the money stays invested in a balanced portfolio of equities, fixed interest and cash and grows enough to match inflation (preserving purchasing power) plus delivering a 3% return on top.

Perhaps controversially, I've assumed that individuals won't have the benefit of the state pension, as some people won't want to rely on this or will be starting withdrawal before they reach state pension age.

Retirement options

1. A 'comfortable' retirement

The Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association this month put together a set of three retirement living standards - basic, moderate and comfortable - based on research by Loughborough University. It hopes these will resonate with pension savers in the same way that being told to eat "five a day" encouraged fruit and vegetable consumption. If you want a "comfortable lifestyle" that allows you to be spontaneous with your money and have two foreign holidays a year, as a single person you'll need to generate an income of £33,000 a year.

Lump sum needed: £1.1 million

2. Be like your peers

Find out what your closest friends are aiming for - it will be a good conversation starter and may even help you with your own goals. However, Interactive Investor's research found knowledge of retirement income appeared shaky among those yet to retire, with 57 % admitting to having no idea, or only a vague idea, of what their household income would be. However, a quarter (the largest group) said they expected to have a household income of between £20,000 and £29,999.

Lump sum needed: £700,000 to £1 million for a couple; £350,000 to £500,000 for an individual

3. The minimum income standard

This data series by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation has been running for many years and recognises that we will need more than just food, clothes and shelter in retirement. However, it covers needs, not wants; necessities, not luxuries - items that the public think people need to "participate in society". In 2019, to reach a minimum acceptable living standard, it found that a single person would need £18,800 per year. The capital you would need to generate this level of income (not including the state pension) is still scarily large.

Lump sum needed: £626,666

4. Replicate (or replace) the state pension

Currently £8,767 a year, the full state pension requires 35 years' worth of national insurance contributions (NICs) and is meant to be enough to live on - but will only support an extremely frugal lifestyle.

I've included this option because we don't know what the future will bring for this universal benefit, which many fear could become means-tested in future. Your NICs simply build up entitlements to whatever is on offer at retirement age (an age that can only rise) with millennials paying for their grandparents' pensions. If there's still state pension left when you get there, treat it as a bonus.

Lump sum needed: £292,233

5. Two-thirds of average earnings at state pension age

Last year, insurer Royal London calculated the sum needed to achieve a "comfortable" retirement income of two-thirds of the average £27,000 a year earnings - so £18,000 per year assuming someone received a full state pension. This calculation also assumed that they had paid off their mortgage and would buy an annuity when they retired.

Lump sum needed: £260,000

If these figures sound daunting, take some comfort from the fact that attitudes to retirement as a time to slow down are changing. Many people have no plans for a complete life of leisure, as shown by the Interactive Investor study.

Nor are pensions and investments the only source of retirement income - buy-to-let property and, increasingly, equity release are helping to square the circle.

You may also find you have more time for money management in retirement - 97% of retirees said they did, compared which 75% of non-retired people. This extends beyond investing. For one respondent, retirement meant "an opportunity to reduce costs by studying comparison sites and other expenditure, which I previously did not have time to do".

What to do if you have too much?

If you have a generous final-salary pension which gives you a guaranteed income that rises in line with inflation, you may not have many money worries, other than busting that £1.055 million pensions lifetime allowance. In this case, you could think about plumping up the pensions of the younger generations in your family.

Half of the respondents to the Interactive Investor survey believed younger generations had it tougher than they did, citing sympathy for the increased cost of housing and student debt.

To get around inheritance tax issues, gifts made from your existing income could enable pension top-ups or ISA contributions for your children or grandchildren. The power of compounding means even small amounts can turn into large sums over long periods - and you'll leave a long-lasting legacy.

Financial help may be particularly important for any women in your family who take time off work to raise a family.

Men and women are not on an equal footing when it comes to investing for the future. Women are more likely to work for fewer years than men because many take career breaks to have and raise children or look after older relatives, and they also live for longer.

As for the grandchildren, helping with Junior ISA contributions (currently capped at £4,368 a year) is a good way to help under-18s build up funds for higher education. For older children, a one-off gift could be a deposit for a first home or help to clear a mortgage.

And finally, it's never too early to start a pension. My daughter was highly amused to learn that even at the tender age of 9 years old, we could theoretically save £2,800 a year into a stakeholder pension for her - topped up by a further £720 worth of tax relief from the government. It's far from a conventional bedtime story, but at least this one stands a better chance of a happy ending.

Moira O'Neill is the head of personal finance at interactive investor. Twitter: @moiraoneill.

This article was written for the Financial Times and published there on 1 November 2019.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.