Our 10 golden rules of investing

Certain tactics can boost your chances of investment success. We reveal the best ones here.

3rd October 2019 09:04

by Kyle Caldwell from interactive investor

Certain tactics can boost your chances of investment success. We run through the rules that can help you become a better investor.

When it comes to the world of investing, there are various traps investors need to navigate. But there are also certain steps that can greatly increase the chances of investment success. Such basic principles are by their nature nothing new; indeed they are subjects Money Observer has covered extensively over the years – but we think if something is important it is worth repeating. With this mind, we pull together 10 golden rules for investors.

1) Spread the word

The first rule is simply to talk about investment and help educate younger family members – children, grandchildren, nephews, nieces – in the importance of investing for their futures.

The reality is that for those below the age of 40, the move from defined benefit or salary-related pensions to defined contribution schemes has shifted the onus to individuals to take control of their financial future. Unfortunately, though, despite the success of auto-enrolment, which now means more than 10 million workers are saving into a pension, most people are not setting enough money aside for later life.

For starters, the importance of not just selecting the default fund option in a workplace pension is a message that needs to be shouted far and wide. The reality is that the default option for most people is likely to be some form of balanced multi-asset fund, which will have been automatically selected by a pension firm as being the 'safe choice'.

The irony, though, is that while such a fund is unlikely to fall like a stone over a short time period, over the longer term it's a missed opportunity. A balanced fund will typically have 40% to 60% in global shares, but those with a 30- to 40-year time horizon can afford to be more adventurous (see infographic below).

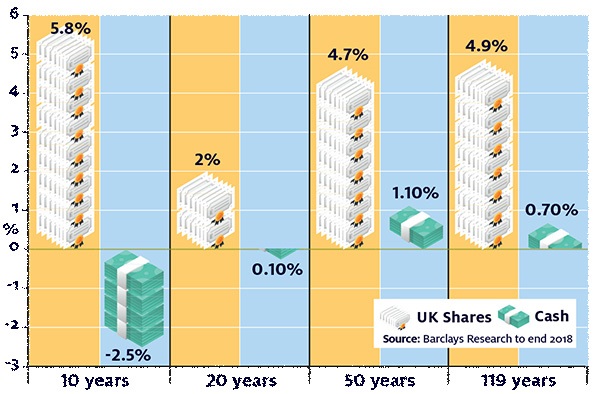

Annual returns versus cash

Rebecca O'Keeffe, head of investment at interactive investor, says:

"Try to take an appropriate amount of risk. Many people take too little risk, ending up as a result with a disappointing return. If your time horizon is long enough, you have time to ride out any short-term swings in the market, allowing you to devote more of your portfolio to higher-risk assets."

Reality check: More generally, the reality is that most people prefer the relative safety of cash. But for those who can invest for the long term, the odds are firmly stacked in favour of stock market investment winning the growth race. The 2019 publication of the Barclays Equity Gilt study, an authoritative report that analyses long-term investment returns, found that over the past decade the stock market has had the upper hand over cash, with UK shares delivering an annualised return of 5.8%, versus -2.5% for cash in real terms (see infographic, below).

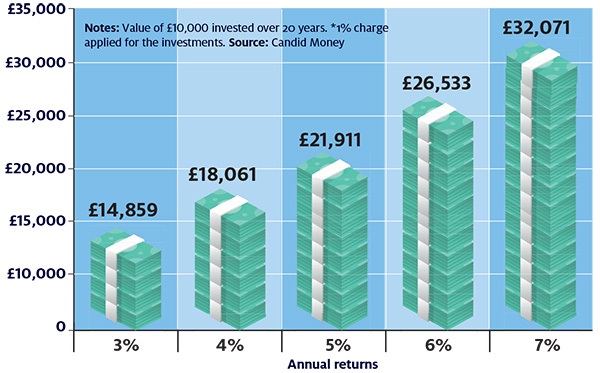

How performance makes a difference

2) Before you invest, pass these tests

Anyone who wants to invest should pass the following three tests before making their first foray into the stock market.

- First, everyone should have some 'rainy day' money for emergencies, ideally three to six months' salary in cash. This will ensure that if something happens and you need to access your cash, you can do so easily and will not have to sell your investments during a potentially disadvantageous time.

- Second, clear debts, tackling the most expensive ones first. While it is important to have rainy-day savings, it is not normally a good idea to prioritise additional savings over reducing debts, because debts usually cost more in interest than savings earn.

- And the third test to pass is to be committed to investing for at least five years, as over the short term the stock market can be pretty unforgiving.

3) Keep an eye on costs

Regardless of how you choose to invest – whether through funds, investment trusts, exchanged-traded funds or individual shares – a certain desired level of investment return over a specific time period cannot be guaranteed in advance.

However, one thing that investors can control is costs. The importance of fees – those levied by fund firms, brokers and financial advisers or wealth managers – has over the years been regularly stressed by Money Observer. Mark Polson, principal at financial consultancy the lang cat, notes:

"It's easy to say 'Ach, it's just 0.3% more expensive, it's nothing'. But that eats into your wealth faster than you would think."

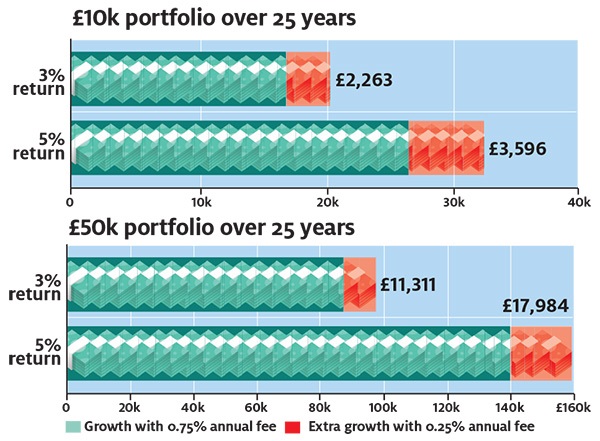

Moreover, higher returns emphasise the difference a higher charge can make. Number-crunching by our parent company interactive investor finds that £50,000 invested over 25 years and growing at 3% a year would be worth £11,311 more with an annual fee of 0.25% rather than 0.75%. At 5% annual growth, that differential rises to almost £18,000 (see chart below).

How annual fees impact returns

Justin Modray, founder of Candid Financial Advice, says: "It is easy to overlook costs, especially when quoted as a percentage. But even a relatively small percentage difference can mean a big difference in pounds and pence." O'Keeffe concurs. She adds:

"A few percentage points of fees may not seem much over one year, but over 20 or 30 years they can seriously reduce your net worth."

When it comes to fund charges, here's the state of play: actively managed funds and investment trusts tend to have ongoing charge figures in the range of 0.7% to 1%, while passive funds – index funds or exchange traded funds – typically cost less than 0.25%. Some active funds and passive funds will charge more or less than these figures and are therefore cheap or expensive relative to their competitors.

But there's nothing wrong with paying a premium, providing the outcome is satisfactory – your fund's performance beats that of rival funds with cheaper charges, for example. After all, it is not desirable to buy a cheaper than average active fund that’s consistently a substandard performer.

Bear in mind that boutique fund managers, those with bigger overheads relative to the number of investors than giant fund groups, will typically impose higher fees. In addition, funds investing in specialist areas or more exotic climates tend to be relatively pricey.

A thesis could be written on the active versus passive investing debate, but the short answer is that a mixture of the two approaches is sensible to help keep costs under control. "This ensures a good blend and reasonable overall fees," says Modray.

When it comes to investment brokers, there are two ways customers are charged. They levy either a percentage fee or a fixed sum; the latter is much easier to get your head around and works out as more cost-effective for larger portfolios (generally those worth £50,000 or more).

Another reason to keep costs under control, notes James Norton, a senior investment planner at Vanguard, is that following the decade-long bull market for stock markets since the financial crisis, "investors need to brace themselves for lower returns over the next decade".

4) Learn from the pros

Swot up to learn how history's greatest investors made their fortunes: Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett and Peter Lynch to name a few. Graham, who tutored Buffett, wrote The Intelligent Investor, which is considered the bible of value investing since its original publication in 1949. Peter Lynch's Beating the Street outlines how to pick good-quality shares at cheap prices, while investors are spoilt for choice in respect to books on Buffett's formulas for stock market success.

Alternatively, all of Buffett's annual shareholder letters over the past four decades, which contain plenty of tips on how to invest successfully, can be read for free online at berkshirehathaway.com. For those who prefer their collection of letters in one place, check out The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America (revised in 2015).

Other investment books beloved of the Money Observer team include: The Investor's Manifesto, written by William Bernstein, Niall Ferguson's The Ascent of Money and Howard Marks’ The Most Important Thing.

5) Diversify - but not too far

The benefit of diversification, spreading your investments far and wide, has been described as "the only free lunch in town". Diversification is achieved through mixing a range of stock market investments with other investment types, primarily bonds and commercial property.

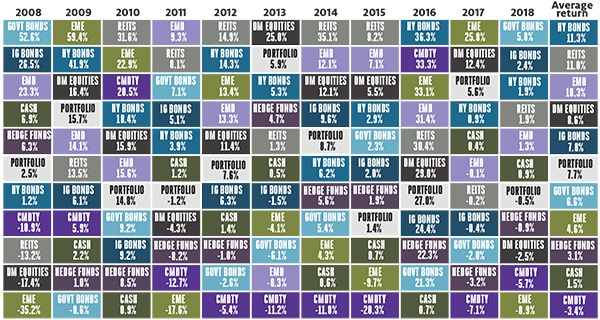

The theory is that different types of investments are unlikely all to outperform or underperform at the same time, which therefore reduces the volatility of your overall portfolio. As the chart below shows, investments perform differently relative to each other every year; a mixed investment approach gives a portfolio ample opportunity to grow, while at the same time guarding against serious short-term losses.

While the theory does indeed work in practice, investors need to avoid the pitfall of over-diversification. This is known as 'diworsification' or inefficient diversification, and occurs if you buy too many funds that are similar – for example, several UK equity income funds. While the fund managers will have their own investment philosophies, and some funds will target shares with high dividend yields while others focus more on dividend growth, the risk is that an investor can end up owning most or even all of the companies in an index. This runs the risk of replicating the market, something that can be done much more cheaply through a passive fund – an index tracker or ETF.

Care also needs to take taken in regard to the 'style' of the fund – value, growth or momentum, for example.

As Justin Modary, founder of Candid Financial Advice, notes:

"Within stock markets, diversification could include mixing large and small companies from across the globe and in different sectors. Doing so via investment funds is a practical way to do so. It is also sensible to combine low cost index-tracking funds with good active managers who invest quite differently."

Allocating to alternatives, such as property, hedge funds, infrastructure and private equity, can also improve diversification. Peter Elston, chief investment officer at Seneca Investment Managers, says such alternative investments "provide the features that give you something similar to bonds". This is pertinent in the current climate, given that the 'safest' type of bond – government bonds or gilts – are looking anything but safe due to their historically low yields. If yields later rise and push prices down, gilt investors are likely to suffer capital losses.

Annualised asset class returns over the past decade

To see a larger version of this chart, click here.

Source: Barclays, Bloomberg, FTSE, MSCI, JPMorgan Economic Research, Thomson Reuters Datastream, JPMorgan Asset Management. Notes: Annualised return covers the period from 2008 to 2018. Govt bonds: Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Government Treasuries; HY bonds: Bloomberg Barclays Global High Yield; EMD: (EM Debt) JPMorgan EMBI Global; IG bonds: Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate – Corporates; Cmdty: Bloomberg Commodity; REITS: FTSE NAREIT All REITS; DM Equities: MSCI World; EME: (EM Equity) MSCI EM; Hedge funds: HFRI Global Hedge Fund Index; Cash: JPMorgan Cash United Kingdom (3M). Hypothetical portfolio (for illustrative purposes only and should not be taken as a recommendation): 30% DM equities; 10% EM equities; 15% IG bonds; 12.5% government bonds; 7.5% HY bonds; 5% EMD; 5% commodities; 5% cash; 5% REITS and 5% hedge funds. All returns are total return, in GBP. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of current and future results. Data as of 31 December 2018.

6) Take advantage of smaller company strength

A powerful investment phenomenon is likely to continue to play out in the decades to come: the significant outperformance of smaller companies over large ones. It's a trend that is the long-term investor's friend: research in 2019 by the London Business School found that £1 invested in 1958 in the Numis 1000 index, composed of the 1,000 smallest UK-listed companies, would have grown to £15,213 by the end of 2018. In contrast, £1 invested in the FTSE All-Share index over that 60-year period would have grown to just £991.

There are various factors at play as to why small is beautiful – most obviously the fact that it's so much easier for a small company to double or triple in size than it is for a large one. But the big driver, according to Victoria Stevens, co-manager on the Liontrust UK Micro Cap fund, is the perception that investment risks are higher for smaller companies.

She adds:

"As a result, shares in these companies may effectively include a risk discount in their prices. If fears prove unfounded and a company successfully grows, you earn a return premium as the share valuation rises."

7) Invest regularly rather than all at once

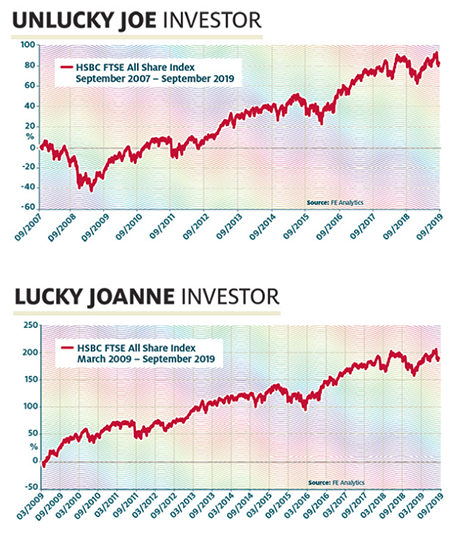

Trying to time the market is often described as a fool’s errand – and with good reason, as those who buy at the wrong time can end up nursing painful losses. The financial crisis is a case in point: the charts below show how the HSBC FTSE All Share Index fund fared for 'unlucky Joe' and 'lucky Joanne'. Joe invested a lump sum at the start of September 2007, shortly before the financial crisis erupted, while Joanne timed her entry into the market perfectly as she bought at the start of March 2009, which marked the start of a strong recovery that has seen the market heading upwards ever since, with some bumps along the way.

As the chart shows, Joe could have lost as much as 40% if those losses were cashed in; given fear was spreading like wildfire, it is feasible he would have lost his nerve. Moreover, if Joe did sit tight, he would have been waiting for around five years until his investments were firmly back in positive territory.

The reliable way for an investor to reduce the risk that they enter the market at a disadvantageous time is to dripfeed money into an investment on a monthly basis. This strategy benefits from what is known as pound-cost averaging. "When we invest the same amount on a regular basis, we simply buy more when an investment is cheaper and less when it is more expensive," explains Juliet Schooling Latter, a research director at FundCalibre. She adds the "little but often" approach reduces risk. "Very few investors can predict the direction of the market in the short term, and getting it wrong can be costly," she says.

Investing regularly also takes the "emotion out of investing", a behavioural flaw that can prove detrimental to returns. Ben Yearsley, director of Shore Financial Planning, notes:

"Lump-sum investors need to be brave enough to invest all when they think they are at the bottom of the market, as well as cashing in at the top. Over time, the averaging effect of pound-cost averaging reduces the risk of getting market timing wrong."

Generally speaking, when markets are buoyant, lump-sum investing wins out over investing regularly on a monthly basis. Research by FundCalibre shows those who invested £100 a month into a passive fund tracking the FTSE 100 in 2017 - a good year - would have ended up with £1,280.80 at the end of the year. Those who had invested £1,200 on the first day of the year as a lump sum ended the year with £1,343.40. However, the same process again in 2018, when the market fell, would have resulted in a lump sum of £1,200 being reduced to £1,095.18, while monthly savings would have been worth £1,114.23 – still a slight loss, but less painful.

"Too many investors look at their portfolios too often. Spend the time doing your research before you buy and then sit back," adds Yearsley.

8) Always make use of your ISA wrapper

Make sure as much of your portfolio is sheltered from the taxman as possible. The amount that can be tucked away in the tax-efficient ISA wrapper has never been more generous: £20,000 can be set aside in the 2019/20 tax year.

The choice has also been expanded over the years, with the appeal broadened to make ISAs more attractive across the generations, via the Lifetime ISA, Help to Buy ISA and Innovative Finance ISA.

Ideally, both pension and ISA allowances should be utilised. Both have their pros and cons: pensions offer more generous tax relief and can be passed on free of inheritance tax, but unlike pension savings, which cannot be touched until age 55, ISA money is readily available in an emergency.

9) Reinvest your dividends

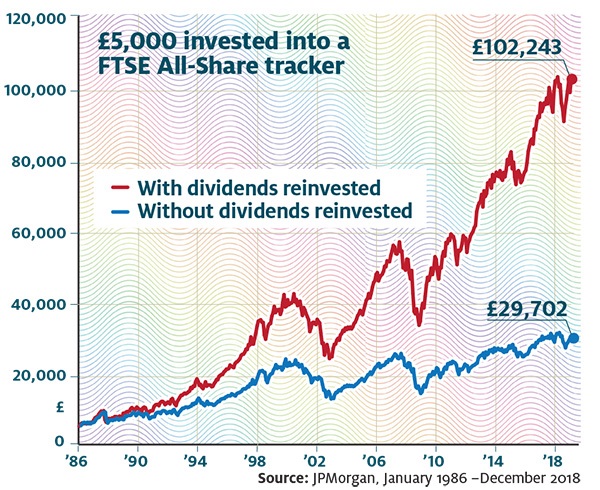

The power of reinvesting dividends makes an enormous difference to long-term investment growth, as the effect of compounding works its magic. Compound growth refers to the way investment returns themselves generate gains. For instance, if you invest £1,000 into a fund returning 5% over one year, you'll earn £50. Assuming that you don't withdraw any money, the next year you'll earn 5% on £1,050, which is £52.50.

This doesn't sound like much of an uplift, but as each year passes, the compounding effect multiplies. The effect becomes even more powerful when compounded growth is bolstered by the reinvestment of dividends. Indeed, over the long term, dividend growth is where the vast majority of returns come from.

The chart below shows the stark difference between the returns from £5,000 invested in the FTSE All-Share index, according to whether dividends are reinvested or not: £90,503 versus £26,903 over the period from the start of 1986 to the end of 2018.

Power of reinvesting dividends

Timeframe also makes a huge difference. Karen Ward, chief market strategist for the UK and Europe at JPMorgan Asset Management, explains that starting earlier gives investors a huge advantage to "grow their growth" considerably.

"An investor who starts investing £5,000 a year at 25 and reinvests a 5% dividend has a pot at 65 that is over 80% larger than someone who begins 10 years later."

Fund investors buying an income fund need to be careful about their share class choice. The accumulation share class reinvests the income generated by a fund manager back into the fund, while the income share class pays income to the investor in cash. For long-term investors looking to benefit from the wonder of compounding, it is more profitable to pick the accumulation option.

Investment trusts are arguably a better option for income-seekers, due to their ability to hold back up to 15% of income generated each year for a 'rainy day'. Thus, during the financial crisis the vast majority of investment trusts were able to maintain or grow their dividends, whereas nearly all open-ended funds with an income focus cut their dividends.

10) Have an annual springclean

Financial planners advocate that investors should review their portfolio at least once a year – preferably twice. Like most 'tidying-up' jobs, it is not one investors are likely to look forward to, but it is necessary. The reason, as Darius McDermott, managing director of FundCalibre, points out, is due to different sectors, asset classes and economies performing differently over the course of a year.

"This means the relative value of your investments can also shift, so therefore what was a perfectly diversified portfolio a year ago may now need some adjusting."

Thus, doing the annual investment springclean stops complacency creeping into a portfolio. Also take a look at the winners and convert some paper gains into real profits, some of which could then be reinvested into areas of the portfolio that have been underperforming but may soon recover their poise.

McDermott adds that if one of your investments is significantly outperforming everything else, it is tempting to hold on to it or even increase your stake, but holding a large percentage of your money in any one investment increases risk. He adds:

"Simply by failing to address imbalances that may occur naturally after significant price gains or falls, you could be introducing more risk into your portfolio than that with which you’re truly comfortable."

As part of a portfolio review it is a good idea to take a step back and remind yourself of your investment goals and attitude to risk. If they have changed, then so should your portfolio. Also, consider whether the investments are still doing what you want them to do, such as paying a rising income; if this is no longer being achieved then consider alternatives. "It is also worth trying to find out why investments have done well or badly before you take profits or top up," says Ben Yearsley of Shore Financial Planning.

James Norton, a financial planner at Vanguard, also makes the point:

"It may seem counter-intuitive to sell your winners, but maintaining the risk level of your portfolio is much more important than chasing returns. It means you're less exposed when markets fall."

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.