Seven times the experts got it very wrong on the economy

16th January 2023 13:01

by Alice Guy from interactive investor

We're on the cusp of a global recession, but experts make mistakes. Alice Guy examines seven howlers from history, and why we should keep calm and carry on investing.

Wouldn’t it be great if we had a crystal ball to predict future stock market and economic trends?

Unfortunately, even for economists and investing experts, that crystal ball is cloudy at best, and often deeply flawed.

In reality, experts can, and often do, get it wrong on their favourite subject. Surely, if they always got it right, they would be rich beyond their wildest dreams by now and be enjoying the fruits of their labour.

- Invest with ii: Open a Stocks & Shares ISA | What is a Stocks & Shares ISA? | ISA Offers & Cashback

Here then, are seven times the experts got it wrong on the economy. It’s an important reminder of why you should block out the noise and keep focused on long-term investing goals.

1) Wall Street crash

In 1929, three days before the famous Wall Street crash, celebrated economist Irving Fisher confidently claimed that “stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau”.

He was proved wrong 72 hours later in spectacularly fashion, as record gains during the 1920s turned to dust. The stock market plunged 89% and took until November 1954 to climb to the same level.

Despite this embarrassing episode, his reputation was later rehabilitated, and Milton Friedman named him “the greatest economist the United States has ever produced”. He is still known for work including the Fisher equation, the Fisher hypothesis and the Fisher separation theorem, which are still cited by economists today.

It just goes to show that a great reputation and intellect doesn’t stop economists from calling it wrong.

2) E-commerce and the internet

Just like the stock market, consumer and technology trends are extremely hard to predict.

In 1966, Time magazine predicted that, “remote shopping, while entirely feasible, will flop—because women like to get out of the house, like to handle merchandise, like to be able to change their minds”.

This rather sexist prediction turned out to be a dud as catalogue, and later internet, shopping took off with a vengeance.

Likewise, the internet was tipped for abject failure by Robert Metcalfe, the co-inventor of the ethernet. In a 1995 issue of IT magazine InfoWorld, he famously claimed that the internet would “soon go spectacularly supernova and in 1996 catastrophically collapse” and promised to eat his words if he was wrong.

Taking his embarrassment in good humour, he was true to his words. During a keynote speech in 1997, he delivered on his promise, put the magazine in a blender and ate it before a live audience.

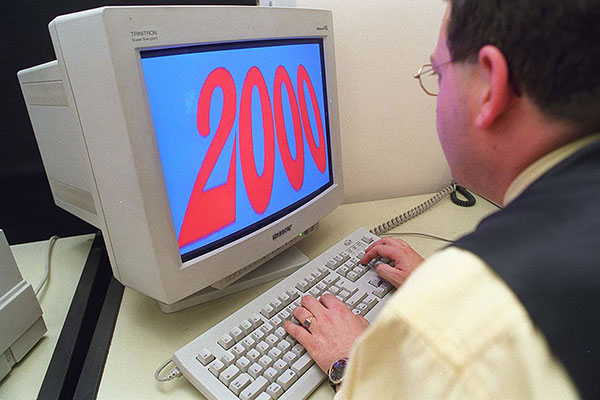

3) Y2K

When it comes to overblown doom-mongering, Y2K has to be up there with the best!

Younger readers probably won’t remember the widespread panic as the year 2000 approached and IT gurus realised there might be a problem. Most software was written with only two digits for the year and experts feared computers would think that 2000 was in fact 1900 – there was no way of knowing what might happen.

Some people predicted that personal data would be compromised, database problems would cause food shortages and even that nuclear missiles might launch themselves. Edmund DeJesus, editor of BYTE magazine, warned that “Y2K is a crisis without precedent in human history”.

Thankfully, it was all a damp squib, and the world didn’t end in January 2000!

4) Dot.com bubble

The new millennium began with the stock market riding high, and at least two brave experts predicted it would stay that way.

In the 1999 book Dow 36,000, James Glassman and Kevin Hassett predicted that the boom would continue, claiming that the Dow Jones Industrial Average would rise from around 16,000 to 36,000 in three to five years.

They told investors, “if you are worried about missing the market’s big move upward, you will discover that it is not too late. Stocks are now in the midst of a one-time-only rise to much higher ground–to the neighborhood of 36,000 on the Dow Jones Industrial Average.”

- Where technology stocks go next after a tough year

- Terry Smith sells two tech stocks after big losses

Sadly, they were wrong, and instead the dotcom bubble burst and the stock market took a nosedive in 2001.

The authors have since claimed that their buy and hold strategy was right, although the title has gone down in investing history as the triumph of optimism over reality.

5) 2008 crash

Another time when many experts didn’t spot an incoming disaster was the financial crash in 2007 to 2008.

In April 2007, former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson claimed that, “I don't see (subprime mortgage market troubles) imposing a serious problem. I think it's going to be largely contained.”

Other experts agreed. Political and economic commentator Ben Stein commented on Fox News that, “the credit crunch is way overblown...The subprime problem is...a tiny problem in the context of this economy...it’s a buying opportunity, especially for the financials – maybe as I’ve never seen before in my life.”

But the subprime mortgage problem turned out to be enormous.

Billions of dollars worth of highly valued bank assets were proved worthless, and a ripple affect led to plunging bank share prices across the world. By the end of 2007, a financial disaster was unfolding and Lehman Brothers, previously the fourth-biggest investment bank in the US, filed for bankruptcy.

At the end of 2007, Merrill Lynch was forced to write off $8.2 billion (£6.7 billion) of worthless mortgages, and in 2008 the troubled firm was bought by Bank of America for less than $20 billion.

6) Dr Doom

One economist who did predict the 2008 financial crash isNouriel Roubini,professor of economics at New York University’s Stern School of Business.

He is jokingly known as “Dr Doom” for his often-pessimistic financial predictions. But even he didn’t always get it right.

In October 2009, Roubini commented that, “I don’t believe in gold...Yeah, it can go above $1,000, but it can’t move up 20-30%.” Despite this prediction, the gold price did rise over the next 18 months, soaring through the $1,000 barrier to over $1,400.

In May 2010, Roubini predicted that equities would fall by 20% in the next few months, commenting that: “there are some parts of the global economy that are now at the risk of a double-dip recession.”

But that stock market crash never happened, and the S&P 500 continued to rise until 2022, with relatively small corrections along the way.

7) ‘Inflation is transitory’

In more recent years, economists have continued to sometimes get their predictions wrong.

In March 2021, Jerome Powell, chair of the Federal Reserve in the US, told Americans not to worry about increasing inflation (2.6% at that time, and rising to 4.2% in April). He believed that “one-time increases in prices are likely to have only transient effects on inflation”.

This was the prevailing view at the time among economists. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen also commented that she expected inflation to drop by the end of the year.

A Bank of England Monetary Policy Report in November 2021 repeated the same message: “We expect inflation to rise to around 5% in spring next year. We expect these high rates of inflation to be temporary. We...think the impact of higher oil and gas prices will fade.”

- What an inflation shock really looks like

- Bond Watch: why US inflation is falling faster than UK inflation

They were all wrong, and inflation soared across the world, hitting 11.1% in the UK in October 2022. Inflation still remains stubbornly high, only beginning to cool in late 2022.

A recession in 2023?

If the last year has proved anything, it’s shown how difficult it is to predict the future. In January 2022, not many of us foresaw Putin’s invasion of Ukraine with its resulting impact on energy prices and the wider economy.

And looking forward, it’s almost impossible to know how China’s lockdown policy will evolve and what other events are lurking around the corner.

But what about 2023? What do the experts predict for the coming year? Will we face a global recession, and if so, how bad will it be?

- Why I’m feeling optimistic about investing in 2023

- 10 quality shares in sectors that can fend off recession

Preston Caldwell, Morningstar’s head of US economic research, believes the likelihood of a US recession is a virtual coin toss and impossible to predict.

In contrast, Nouriel Roubini believes we’re in for a “severe and protracted” recession. He argues that, “if you want to raise interest rates enough to get inflation back to 2%, you have to cause a recession” and claims that it will be short and shallow are “nonsense”.

Meanwhile, figures out last week show that the UK economy grew 0.1% in November 2022, rather than shrinking 0.2% as expected. Despite this, many economists are still predicting a shallow UK recession in 2023.

Commenting on how investors should react to economic forecasts, Marta Norton, chief investment officer at Morningstar, admits the limits of forecasting, commenting that, “the market, while typically quite good at pricing in possibilities, has been consistently off the mark on inflation—and interest rates—over the past year”.

Rather than predicting the future, she suggests that investors should concentrate on preparing their portfolio for a range of possibilities, focusing on planning not forecasting.

Economists have been wrong in the past and they’ll be wrong again in the future.

As for me, recession or not in 2023, I’m sticking with my long-term strategy of regular investing, rather than trying to time the market. And while I admit to sometimes reading economic forecasts, I’m going to remember to take them with a very large pinch of salt.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.