Why stagflation is likely and how to protect your portfolio from it

Analysis by Kepler Trust Intelligence points to a short, but unpleasant, period of stagflation.

17th July 2020 15:48

This content is provided by Kepler Trust Intelligence, an investment trust focused website for private and professional investors. Kepler Trust Intelligence is a third-party supplier and not part of interactive investor. It is provided for information only and does not constitute a personal recommendation.

Material produced by Kepler Trust Intelligence should be considered a marketing communication, and is not independent research.

Analysis by Kepler Trust Intelligence suggests a combination of cost-push inflation and economic hardship could lead to a short, but unpleasant, period of stagflation.

Thomas McMahon, senior analyst at Kepler Trust Intelligence.

Your author had a dentist appointment booked for the day after dentists were ordered to stop work in March. Luckily he was able to finally have the work done two weeks ago, with a £38 surcharge for PPE.

Meanwhile anyone celebrating the lifting of lockdown with a haircut has probably noticed a similar price increase, as companies pass on the extra costs they have incurred in complying with the new regulations.

We suspect that many people are underestimating the inflation that is coming down the tracks, and that we could well see a period of stagflation [a combination of high inflation, stagnant demand and high unemployment] as the economic fallout from the pandemic starts to bite.

Another early sign of this inflation has come through in the numbers reported by the supermarkets for the lockdown period. Sainsbury's (LSE:SBRY), for example, saw sales grow by 10.5% in the quarter to June but expects full year profits to be flat, despite the tax breaks allowed by the government.

Tesco (LSE:TSCO) and Morrison's (LSE:MRW) have also reported that they expect no gain to their bottom line this year, despite rising sales. The chief reason is the impact of social distancing and other health regulations, which have caused a huge spike in the cost of production and are raising inflation for consumers too.

Mind the gap

Many areas of the economy have been closed for most of the past three months, which somewhat limits the scope of what can be said about inflation. Lots of goods and services have not been traded, so there is no answer to the question what their current price is.

However a paper written by Xavier Jaravel and Martin O'Connell for the Institute for Fiscal Studies found that there had been a substantial uptick in inflation felt by consumers through the lockdown period, judged by the increase in the prices of goods and services they could consume; although the uptick may have been hidden as much of it was felt in a sharp reduction in discounted deals and multibuy offers.

Jaravel and O’Connell’s paper tracks the price and quantity of all goods brought into the home by a sample of shoppers. They found an average price increase of 2.4% on goods bought between March and May, which is unprecedented in the dataset going back to 2013.

The advantage of this paper in our opinion is that it looks at what was actually bought rather than trying to estimate what, for example, a haircut would have cost if it was available for purchase (as indices such as CPI do, as they measure a fixed basket of goods). It should be remembered that these are not annualised figures. On an annualised basis, as CPI and RPI are presented, this would represent inflation of around 12%.

In our view, as the economy opens up producers are going to have to pass hefty increases in costs onto consumers – just as the supermarkets have had to. Additionally these costs are unlikely to be quickly reduced.

Digressing into politics for a moment: whatever the truth about the lethality of the virus and the likelihood of a second wave, policy is likely to remain haunted by it over the winter, if nothing else then as a result of fear and the precautionary principle.

For reputational reasons, businesses will also find it hard to push back on the regulations, even if infections remain low. Staffing costs are likely to rise as businesses adapt to obligations to their employees regarding health considerations. For example, no business will want to deny workers two weeks off if they have symptoms, which is problematic given the symptoms of a common cold are similar in mild cases.

We are therefore likely to see a burst of supply-side, or cost-push inflation. This is far more problematic than the demand-pull inflation many in the market have been chiefly worried about in recent years. Demand-pull inflation generally occurs when an economy overheats.

It is, to some extent, a sign of success; or would have been considered so in recent years, as economies climbed slowly out of the ruins of the financial crisis and the ability and desire of households to spend increased. The solution to demand-pull inflation is to raise interest rates to discourage investment at low rates of return.

Unfortunately, there is no straightforward policy solution for cost-push inflation, except to reduce costs. In theory other regulations could be loosened to offset the impact of social distancing costs.

However, it is hard to see what could possibly offset the magnitude of these. The VAT cut for the hospitality sector is an attempt to do just that, and offset the impact of reduced capacity as a result of social distancing measures in the short term.

But more widespread tax breaks are unlikely, given the huge costs of the lockdown which have been piled onto an already indebted government account. A similar result could also be achieved by the government setting prices, but we have to hope that this isn’t another East German policy to make a comeback in 2020.

It is more likely that corporate profit margins will compress as much as possible with companies absorbing much of the costs, but this can only have so much impact; and will also have the side effect of reducing the funds available for reinvestment in the economy and thus reducing growth.

Idle hands

The other wing of stagflation is recession, and it should go without saying that we are experiencing a significant fall in economic activity. There are currently 8.9 million people on furlough, over 25% of the country’s workforce.

Many of them will not come back to a job, although how many is hard to know. One indication of the potential scale of job losses comes from a YouGov poll of businesses (conducted between 22 May and 7 June). Of those asked, 51% said they would have to lay off staff if the furlough scheme ended. As many as 10% said they would have to lay off more than half their employees.

A poll of businesses by LM Research & Marketing Consultancy carried out between 17 and 20 June indicated 25% of furloughed workers were likely to be let go. Added to the 2.8 million who are already receiving out of work benefits, this could see 5 million unemployed in the UK.

So far we are only in the foothills of the unemployment crisis, with the main corporate victims being those generally known to be financially weak before the crisis– Debenhams and various high street and restaurant groups for example – but that will certainly change. Demand for labour and for goods will fall which is a deflationary force.

The evil of cost-push inflation is that it is immune to this: prices will be rising while demand is weakening, with rising prices reinforcing falling demand and therefore economic activity.

More than just a winter of discontent?

This combination of cost-push inflation and high unemployment is described by the evocative portmanteau ‘stagflation’. It is one of the year’s ironies that the Conservative government, which last December defeated a man they pilloried relentlessly as a throwback to the 1970s, could well be creating an economic environment so redolent of that same era.

The 1970s saw a prolonged period of this difficult environment. The inflation in the 1970's was largely imported from the US, which massively expanded government spending to pay for the Vietnam War, and was further fuelled by persistent oil price rises.

At first glance, it seems that the supply shock inflation we are experiencing will be shorter-lived. It seems unlikely that social distancing and related regulations will continue to stiffen in future, and more likely that they represent a one-off single shock.

Although costs will probably be passed slowly onto consumers, this is likely to take several months, as they work through into retail prices. Any persistent inflation after that is likely to require other causes.

One potential longer-term push to inflation could be caused by cutting China out of supply chains and a broader trend to onshoring. This threat could well be more bark than bite, however.

Given the economic pain that is coming down the tracks towards us, there is going to be a huge incentive to return to the cheapest ways of doing business – excluding certain industries with security implications (now to include medical industries).

Another kick to cost-push inflation could be caused by the pound drifting lower. In our view this scenario represents a real risk, given the parlous state of the UK economy and the uncertain impact of Brexit. A hard Brexit could see pressure on the pound, while social distancing regulations and restrictions – as well as the deep recession – would complicate attempts to offset the impact through policy.

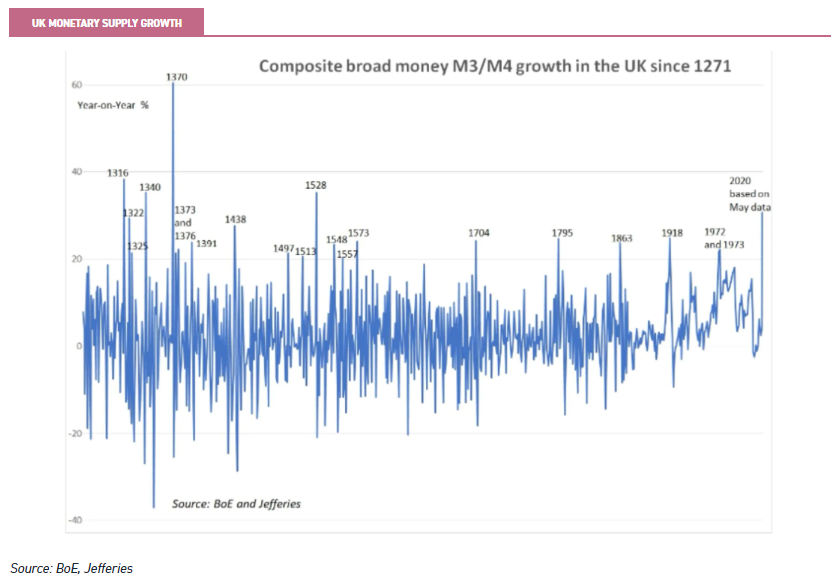

We also have to consider the monetary aspects of the current situation. According to Jefferies research, the growth in the UK monetary supply since the start of the crisis (using the broadest measures) has been the fastest since the reign of Henry VIII (see chart below).

The general pattern is true around the world, and is due to huge central bank purchases of government bonds (QE). The Bank of England, for example, has created £300 billion with which to buy gilts this year.

In theory a rise in the money supply should lead to inflation. In practice, however, the relationship is far more complicated. A lot depends on what happens to that money. One of the lessons from the financial crisis was that the dominant macroeconomic models had an insufficient understanding of the banking system.

Any inflation from the last round of QE was felt in asset prices (equities, house prices) rather than in the real economy, but it would be complacent to assume the same will occur this time.

Lost down the back of the sofa

Will the extra money – £300 billion so far – be absorbed by the financial system again, like last time, or will it produce inflation in the real economy? The last QE programme, conducted in response to the 2007/2008 financial crisis, didn’t see a high period of inflation ensue – at least not in the price indices.

Fundamentally this was because the money was largely used to cover up a debt deflation on banks’ balance sheets. Over a period of years, banks had to recapitalise themselves by working off assets with illusory value and replacing them with the cash injected by central banks.

Excessive debt led to a period of deflation, which was offset by the money pumped into the economy. The inflation was real but merely offsetting large deflationary forces. Furthermore households were already overextended heading into the crisis, meaning that debt was paid down rather than going back into the economy; consequently compounding the reduction in economic activity and slowing the velocity of money.

This kind of process was dubbed a ‘balance sheet recession’ by Richard Koo, initially in relation to the Japanese economy in earlier years but later more widely applied across the globe.

However, it is generally accepted amongst market participants that banks entered this latest crisis in a far better state. Having spent the last few years adhering to the Basel III regulations, banks were required to hold higher levels of capital against their liabilities.

Therefore less money may need to be absorbed by banks’ balance sheets this time. The UK consumer has also used the lockdown period to pay down debt and increase savings, meaning there is cash on the sidelines to come into the economy over the coming months. Household debt was already at more modest levels entering the crisis, at a debt-to-income ratio of 127% in Q4 2019 compared to 147% in 2007.

This backdrop implies the deflationary deleveraging this time should be far weaker, and that overt inflation is more likely to occur. There is the potential, however, for UK banks to have problems with the bounce back loan programme.

These loans are guaranteed by the government but sit on banks’ balance sheets and are administered by them. For reputational reasons it will be hard for the banks to chase repayment or declare defaults, so they may find themselves holding more capital against these possible outcomes. In addition to this, we have to consider the impact of the crisis in the real economy on banks’ balance sheets.

Banks will have to hold more capital against loans as they sour, and will have to take provisions against expected losses in the coming quarters. These additional buffers will be a drain on the monetary system.

Furthermore UK corporates did enter the crisis with high debt levels, increasing their fragility. According to the OECD, UK non-financial corporations faced the fifth highest debt-to-surplus ratio in the developed world.

Although, to be fair, their debt service ratio is relatively low at 35%. All in all, we do think the deflationary impact of one of the most severe recessions in our history will offset much of the impact of QE.

Conclusion: Scylla or Charybdis?

Ordinarily a sudden drop in economic activity should be deflationary in impact. However, as we have argued above, we are already seeing a burst of cost-push inflation thanks to social distancing and health regulations which is likely to continue in the coming months, perhaps the next year.

Accompanied by spiralling unemployment, the result could be a period of stagflation.

Could this continue for a prolonged period? It is easy to see the weak growth part of the situation persisting. We are about to see a tsunami of unemployment which will likely lead to a prolonged slump and to hysteresis: economists’ term for the permanent loss of productive capacity, thanks to the degradation and obsolescence of skills in the workforce.

As for the longer-term prospects for inflation, we are not convinced. Our base case would be a reduction in social distancing restrictions next year, which reverses some of the inflationary impact.

In fact, should the economic news in the final quarter of the year be truly awful, then an easing of restrictions could come sooner than expected and downward pressure on cost inflation emerge.

The open question is about the impact of monetary expansion. As we have argued above, the reduction in demand and need to deleverage should provide offsetting deflationary impulses.

However, we would argue that there is a lurking danger that the Bank of England’s independence is under threat.

The Bank’s mandate is to control inflation, not to finance government spending. While it believes buying government debt is necessary to ride out the crisis by ensuring liquidity in the financial system, it will continue to do so.

When it believes the government is issuing excessive debt to finance everyday spending, it may baulk at doing so. If the Bank stops buying, borrowing costs could rise very quickly. In fact, the likely result of this scenario would be the end of Bank of England independence, which could prompt a loss of confidence in UK debt.

Our base case is, therefore, that we are going to get inflation in the next few quarters; and that the inflation will be accompanied by a recession, thereby fulfilling the definition of stagflation.

Whether we are going to see a longer period of stagflation is less sure; because of the deflationary impact of the recession and the fact the increased costs will at least subside, if not reverse, in the new year.

However, we don’t think the possibility of a medium-term period of inflation can be discounted. Firstly, if infections rise and a nervous population demands it, the government could impose more onerous restrictions and perhaps even more lockdowns.

Secondly, the government may be tempted to push back on central bank independence and demand that the Bank prints money and directly injects it into the economy.

This course of action would also have the helpful effect of reducing the government debt burden by inflating it away. A long shot, maybe, but a real risk which would have seemed impossible from a Conservative government as recently as early February.

Certainly Paul Tucker, former deputy governor of the Bank of England, believes the BoE has already taken steps down this road and that consequently its independence is in question.

Protection

A period of stagflation would mean weak economic growth and inflation. On an asset class basis this outcome would be poor for equities over the medium term, thanks to the impact of a recession.

Rising costs would eat into profits and struggling consumers would be less likely to cope with price rises. Nominal bonds would also suffer as inflation ate away at their gains.

Inflation-linked bonds would do well, however, guaranteeing a real return. This is the logic that has seen Ruffer Investment Company hold 32% of NAV in index-linkers.

The managers are particularly concerned about the impact of government spending as a response to the pandemic on inflation, as we discussed in our latest note on the trust.

Commodities could also benefit in our view. Apart from gold, which would benefit as a store of value, the producers of industrial commodities (such as oil or agricultural commodities) could also pass on price rises.

How this would work through the income statement of these companies, and whether the producers would be net beneficiaries after accounting for falling demand, is a more complex question however.

Last week we published a note on BlackRock Energy and Resources Income (LSE:BERI), which balances exposure to the traditional commodities with a growing allocation to ‘energy transition’ stocks; which are likely to be the recipients of greater regulatory assistance in the coming years.

Within equities, investors should probably prefer defensive industries. In other words those which are able to pass on costs to consumers: consumer staples for example, as well as healthcare and utilities (taking into consideration regulatory price caps). The portfolio of Troy Income & Growth (LSE:TIGT) has strong biases to staples and healthcare, which would benefit it in such an environment over the medium term, though in the short-term the market may overlook these companies' ability to pass on prices.

We will be publishing an updated research note on this trust in the near future.

In our view, these defensives should also include many digital industries. As we discussed in a recent strategy note, software and internet companies – which are light on capital and with increasing returns to scale – have been behaving like defensives on the downside.

We believe this trend could well continue in a ‘stagflationary’ environment, as they offer essential goods and services with capital light business models which mean they are less affected by input price rises.

Labour would be a relatively muted source of inflation in a stagflation scenario, as unemployment would be high, meaning workers’ bargaining power would be low. Scottish Mortgage has a portfolio full of such companies.

And in a stagflationary environment interest rates would likely remain low, which would support the valuation of their portfolio, as we discussed in our recent note. Another option that is less exposed to ‘extreme’ growth is Allianz Technology Trust (LSE:ATT), which offers a relatively concentrated specialist exposure to global technology stocks.

In recent months ATT has moved more into companies positioned to benefit from remote working and a stay-at-home environment, including software companies providing cyber security, workforce collaboration, video streaming, and communication services. All of which benefit from capital-light business models and increasing returns to scale.

Kepler Partners is a third-party supplier and not part of interactive investor. Neither Kepler Partners or interactive investor will be responsible for any losses that may be incurred as a result of a trading idea.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Important Information

Kepler Partners is not authorised to make recommendations to Retail Clients. This report is based on factual information only, and is solely for information purposes only and any views contained in it must not be construed as investment or tax advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or take any action in relation to any investment.

This report has been issued by Kepler Partners LLP solely for information purposes only and the views contained in it must not be construed as investment or tax advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or take any action in relation to any investment. If you are unclear about any of the information on this website or its suitability for you, please contact your financial or tax adviser, or an independent financial or tax adviser before making any investment or financial decisions.

The information provided on this website is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Kepler Partners LLP to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. Persons who access this information are required to inform themselves and to comply with any such restrictions. In particular, this website is exclusively for non-US Persons. The information in this website is not for distribution to and does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of any offer to buy any securities in the United States of America to or for the benefit of US Persons.

This is a marketing document, should be considered non-independent research and is subject to the rules in COBS 12.3 relating to such research. It has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research.

No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by any person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and no responsibility or liability is accepted for the accuracy or sufficiency of any of the information, for any errors, omissions or misstatements, negligent or otherwise. Any views and opinions, whilst given in good faith, are subject to change without notice.

This is not an official confirmation of terms and is not to be taken as advice to take any action in relation to any investment mentioned herein. Any prices or quotations contained herein are indicative only.

Kepler Partners LLP (including its partners, employees and representatives) or a connected person may have positions in or options on the securities detailed in this report, and may buy, sell or offer to purchase or sell such securities from time to time, but will at all times be subject to restrictions imposed by the firm's internal rules. A copy of the firm's conflict of interest policy is available on request.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The value of investments can fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested when you decide to sell your investments. It is strongly recommended that Independent financial advice should be taken before entering into any financial transaction.

PLEASE SEE ALSO OUR TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Kepler Partners LLP is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales at 9/10 Savile Row, London W1S 3PF with registered number OC334771.

Kepler Partners LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Kepler Partners is a third-party supplier and not part of interactive investor. Neither Kepler Partners or interactive investor will be responsible for any losses that may be incurred as a result of a trading idea.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Important Information

Kepler Partners is not authorised to make recommendations to Retail Clients. This report is based on factual information only, and is solely for information purposes only and any views contained in it must not be construed as investment or tax advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or take any action in relation to any investment.

This report has been issued by Kepler Partners LLP solely for information purposes only and the views contained in it must not be construed as investment or tax advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or take any action in relation to any investment. If you are unclear about any of the information on this website or its suitability for you, please contact your financial or tax adviser, or an independent financial or tax adviser before making any investment or financial decisions.

The information provided on this website is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Kepler Partners LLP to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. Persons who access this information are required to inform themselves and to comply with any such restrictions. In particular, this website is exclusively for non-US Persons. The information in this website is not for distribution to and does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of any offer to buy any securities in the United States of America to or for the benefit of US Persons.

This is a marketing document, should be considered non-independent research and is subject to the rules in COBS 12.3 relating to such research. It has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research.

No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by any person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and no responsibility or liability is accepted for the accuracy or sufficiency of any of the information, for any errors, omissions or misstatements, negligent or otherwise. Any views and opinions, whilst given in good faith, are subject to change without notice.

This is not an official confirmation of terms and is not to be taken as advice to take any action in relation to any investment mentioned herein. Any prices or quotations contained herein are indicative only.

Kepler Partners LLP (including its partners, employees and representatives) or a connected person may have positions in or options on the securities detailed in this report, and may buy, sell or offer to purchase or sell such securities from time to time, but will at all times be subject to restrictions imposed by the firm's internal rules. A copy of the firm's conflict of interest policy is available on request.

Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The value of investments can fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested when you decide to sell your investments. It is strongly recommended that Independent financial advice should be taken before entering into any financial transaction.

PLEASE SEE ALSO OUR TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Kepler Partners LLP is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales at 9/10 Savile Row, London W1S 3PF with registered number OC334771.

Kepler Partners LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.