More like set-it-and-regret-it: what the pros are using instead of the 60/40

When stocks and bonds fell in unison, the pros adopted the Total Portfolio Approach. Here’s how it works.

21st November 2025 08:48

by Theodora Lee Joseph from Finimize

- The old 60/40 playbook has broken down. Big investors now manage risk and return as one connected system – not separate buckets

- The Total Portfolio Approach lets capital flow wherever risk, liquidity, and opportunity line-up

- Retail investors can’t copy a big sovereign wealth fund exactly – but goal-based, flexible investing will get them pretty close.

For years, Strategic Asset Allocation (SAA) was all the rage in investing.

You’d just decide on a long-term mix – say, the classic 60/40 portfolio, with 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds – and rebalance every so often to keep the levels in check. It was steady, disciplined, and comforting in its simplicity.

But a few years ago, markets shifted.

Inflation surged, and everyone suddenly saw that bonds don’t always rise when stocks fall. Sometimes, those two assets fall together. And that made the old 60/40 balance seem, well, not at all balanced.

That tough lesson has led some of the world’s biggest investors to toy with a new way of thinking – one that treats the portfolio as a single, living system instead of rigid parts. It’s called the Total Portfolio Approach (TPA). And there’s a lesson in this for retail investors.

So, what exactly is the Total Portfolio Approach?

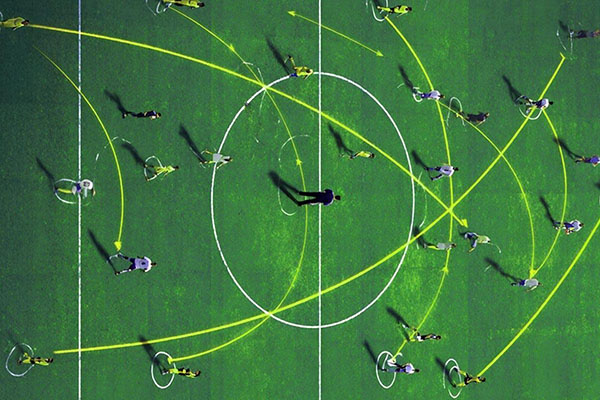

If SAA is like sticking to a rigid football formation no matter what, TPA is real-time coaching. It looks at how the entire team is performing and makes changes mid-game – swapping players, adjusting tactics, moving toward the best opportunities.

Rather than saying “we must have exactly 60% in stocks”, TPA investors ask: how much risk are we talking overall? What’s pulling its weight? How do these assets work together?

Capital flows to wherever offers the best returns for the risk taken. If infrastructure looks better than stocks, money moves. If private credit tops corporate bonds, funds shimmy. It's dynamic, opportunity-driven, and definitely not set-it-and-forget-it.

Here's an example. Let’s say a sovereign wealth fund notices that stocks look expensive, but private infrastructure projects – toll roads, renewable energy farms – offer attractive long-term returns with less volatility. Under the old model, they'd be stuck if their stock allocation was already at target. Under TPA, though, they can simply adapt, adjusting their allocations to fit the opportunity.

For the professional funds that make this shift, the whole workplace changes. Investment committees stop being organized by asset class – the stock team versus the bond team – rather, they collaborate to maximize the portfolio’s overall return. Every decision is measured against actual goals like funding people’s retirements or building sovereign wealth, rather than maintaining arbitrary benchmarks for how much money sits in each bucket.

Why the change?

The switch to TPA didn’t happen overnight. It’s the result of more than a decade of frustration with static, hard-coded diversification.

First, interest rates stayed near zero for years after the global financial crisis. That made borrowing cheap and risk-taking easy – great for buying homes and stocks – but terrible for the part of your portfolio that’s meant to protect you. Bonds were no longer providing income or acting as a buffer, because when yields are that low, their prices have nowhere to go but down when rates rise.

Second, when inflation surged in 2022, stocks and bonds fell together. The 60/40 portfolio relies on bonds zigging when stocks zag. Instead, both zigged off a cliff at the same time – exposing just how vulnerable the old strategy can be.

Third, the world became risky in a new way. Powerful governments began using trade as a weapon, wars affected key energy routes, and supply chains that had become densely concentrated in certain parts of the world were suddenly able to spread shocks faster than ever.

A portfolio frozen to old assumptions just couldn’t dodge punches that came from so many new directions.

Big players saw it happening. Canada’s big CPP and OTPP pension funds, New Zealand's Super Fund, and Australia's Future Fund all started experimenting with TPA years ago. And when 2022 hit, they looked very smart indeed.

TPA lets investors act fast when conditions shift and to spot the risks they didn’t mean to take. When AI stocks boom, every asset-class team might unknowingly pile into similar exposures – tech stocks, AI-driven infrastructure, AI-linked private credit – creating hidden risk. TPA makes those overlaps visible.

Where’s the money going?

When the world’s biggest pools of money start thinking this way, the ripple effects are huge.

More money flows into private markets and alternatives. Because TPA investors aren’t constrained by those set allocations, they can chase returns in private equity, infrastructure, private credit, and whatever else takes their fancy. Everything essentially competes on the same playing field: a real estate opportunity in Singapore competes directly with tech stocks in Silicon Valley – and the assets that offer better risk-adjusted returns win the capital.

Correlations matter more. TPA investors obsess about diversification – not just owning different stuff, but about how assets move in relation to each other.

Liquidity becomes a weapon: investors who manage their cash well can strike when others can’t. That drives lots of demand for liquid alternatives: flexible funds that offer private-market-like returns.

But there are risks, of course. When everyone allocates fast, herding happens fast, too. If global funds are all using similar data and models to decide what’s attractive, they can end up crowding into the same trades – piling into infrastructure one year, private credit the next – and then all rushing for the exits when conditions change. That can amplify swings instead of smoothing them.

And what does this mean for regular investors?

You’re probably not running a sovereign wealth fund with hundreds of billions of dollars to manage – but you can absolutely steal the best moves from those giants.

The retail investing version of this is called “Goals-Based Investing”. To use it, you focus on what you need your money to do, and forget about hitting some arbitrary “60% stocks” target.

Instead, get specific about what you’re actually saving for – retirement in 15 years, buying a home in three years, your kid’s university expenses in 10 years. Prioritise goals like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: food, shelter, and medical care come before aspirational stuff like that dream sailboat.

Your entire financial life is already one big portfolio. That includes your investments, sure, but also your home equity, your salary, and even the benefits you’ll draw in retirement. Your earning power is an asset too. So, when you’re eyeing a new investment, don’t ask “do I have enough stocks?” Ask “will this improve my whole financial picture?”

Stay flexible, adapt when the world does, and adjust your portfolio when markets throw you opportunities or threaten big losses. Don't be stubborn about percentages you dreamed up five years ago when the world was completely different.

And sure, you don’t have a team of PhD mathematicians or access to private infrastructure deals. But you do have one key advantage: clarity on what matters most to you.

Theodora Lee Jospeh is an analyst at finimize.

ii and finimize are both part of Aberdeen.

finimize is a newsletter, app and community providing investing insights for individual investors.

Aberdeen is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.