Stockwatch: the biggest problem facing global financial markets?

When something is worrying the CEO of America’s biggest bank, a bond ‘king’ and the man who called the 2008 crash, it’s probably worth taking notice. Analyst Edmond Jackson outlines the arguments for both sides.

2nd February 2024 11:52

by Edmond Jackson from interactive investor

It continues to prick global financial debate, just lately with JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon, Bill Gross who is co-founder of giant bond fund PIMCO and now Nassim Taleb, who correctly called the 2008 financial crisis – all warning of disruptive consequences.

Taleb may attract more attention as the celebrated risk analyst and financial trader who originated “black swan” theory of randomness and a sense for “tail risk” when investing.

- Invest with ii: Open a Stocks & Shares ISA | ISA Investment Ideas | Transfer a Stocks & Shares ISA

Reputedly, he became financially independent after the 1987 stock market crash, profited from the 2000 tech-stock collapse also the 2008 crisis as it unfolded from 2007.

He actually describes US debt as a “white swan”, a risk more probable than a surprise black swan event. He argues it is becoming more pertinent given the US economy is more vulnerable to shocks nowadays, and globalisation has made the world more interconnected, hence issues in one region ricochet to others.

US debt levels have soared, but so they have globally

Dimon’s frustration is illustrated by the way US federal debt as a percentage of GDP has risen from around 35% when he left high school to around 120% now, involving $34 trillion.

It follows a hockey-stick chart, starting relatively sideways then spiking. He anticipates “a rebellion” in about 10 years’ time given foreign investors own $7.6 trillion of it, chiefly Japan with $1.1 trillion.

Looking at 2022 numbers from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), yes, the US is a concern in terms of public debt. At 121% of GDP, it is second only to Japan at 261% and ahead of the UK at 101%. But it is hardly an outlier versus 114% for advanced economies generally.

General Government Debt (per cent of GDP) | ||||||

2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2022 | |

China | 23.0 | 26.3 | 33.9 | 41.5 | 70.1 | 77.1 |

France | 58.9 | 67.4 | 85.3 | 95.6 | 115.1 | 111.7 |

Germany | 59.3 | 67.5 | 82.0 | 71.9 | 68.0 | 66.5 |

Italy | 109.0 | 106.6 | 119.2 | 135.3 | 154.9 | 144.4 |

Japan | 135.6 | 174.6 | 205.9 | 228.3 | 258.7 | 261.3 |

UK | 37.7 | 41.0 | 75.7 | 87.7 | 105.6 | 101.4 |

USA | 53.2 | 65.4 | 95.1 | 105.1 | 133.5 | 121.4 |

Source: International Monetary Fund | ||||||

Adding private debt means China at 272% of GDP is close to the US at 274% and the UK not far behind at 252%.

Global total debt as a percentage of GDP has thus grown relentlessly – accentuated by Covid support programmes – and is worst in advanced economies. While that might relate to high and maturing populations, in a public debt sense the biggest problem could therefore lie ahead – in terms of pension and healthcare provision.

Japan’s long-term experience with high debt since the 1980s is a disappointing harbinger for the rest of us. Its economy has been in the doldrums for decades and is soon likely to be overtaken by Germany. What a contrast with the 1980s when Japan was taught in economics classes as a post-war growth miracle.

- Sign up to our free newsletter for share, fund and trust ideas, and the latest news and analysis

- The Analyst: Dzmitry Lipski’s investment insights

This is a global not US-specific problem, although given the US is expected to act as a global hegemon on behalf of the West, it is of increasing concern for stability if the US cannot sustain defence spending. For example, Republican calls for the US to cut support for Ukraine.

Yes, governments can in principle borrow as much as they like, but as Liz Truss found to her cost in 2022, markets will price for the financial context, and rising debt service costs compromise governments’ meeting their objectives, be it social needs, infrastructure or climate.

US debt ceiling stand-offs encourage sense of complacency

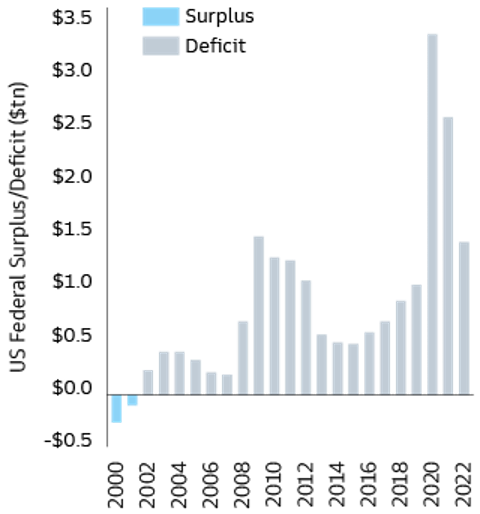

The US has experienced a budget deficit every year for the past 22 years, yet a budget surplus only five times in the last 50 years. Its lawmakers have attempted to control the uptrend by way of debt ceilings, which initially panicked investors but just led to periodic stand-offs before Congress would capitulate to raise the ceiling.

Last autumn, an ironically named Fiscal Responsibility Act suspended any such limit until 2025 which provoked Fitch to downgrade the US sovereign rating from AAA to AA+. This came as no major shock to markets but underlined a deterioration in US finances.

Investors have become accustomed to it, albeit at risk of “the problem of induction” where you assume past performance informs the future, only eventually to get a rude shock, perhaps.

I recall Professor Nouriel Roubini aka “Dr Doom” declaring in early 2010 that US equities were exposed to further downside (post the great financial crisis and recession) given an imminent crisis over the US debt ceiling. Instead, there followed the greatest long-term stock market rally in financial history.

- Vodafone among dozen blue-chips about to pay £4.4bn in dividends

- Solid dividends are reward for owning these great companies

Goldman Sachs makes a rather apologist case, about how the US fiscal situation is no short to medium-term threat given the credibility and demand for US assets. But they concede more enforcement of discipline on government spending is needed. They predict the interest expense alone on federal debt will reach 3.8% of GDP by 2028, versus an average 1.8% annually since 1945.

Fitch similarly projects higher debt service costs, such that the interest-to-government revenue ratio in the US will hit 10% by 2025 versus a median 2.8% for AA-rated countries and 1% for AAA.

US Federal surplus/deficit ($ trillion) since 2000

Source: Federal Reserve economic data

US assets prevail as both desirable and investable

Goldman also argues US debt sustainability is “not a guaranteed, long-term threat”. Strength as a global economic power reinforces US credibility and ultimate promise to pay off its debt: “While the path to sustainability will not be easy, ample access to capital provides the US government a buffer in its search for fiscal discipline...”

I can agree there is a scenario where the US muddles through. But what if it gets sucked into Middle East conflict adding further to its debts, then China decides it is opportune to invade Taiwan? Goldman’s argument feels to me, quite the best-case scenario of various potentials, and somewhat apologetic-nationalistic.

This extends to Goldman proclaiming US financial assets as desirable and investable in global portfolio context. They would say that, wouldn’t they as a prime US investment banker aiding their issuance.

A ‘boiling frog’ situation, according to JP Morgan

The US Congressional Budget Office estimates debt service costs will exceed total government revenue by 2023. Analysts at JP Morgan have employed the metaphor where if a frog is suddenly put into boiling water, it will leap out, but in tepid water brought to boil it will not perceive the danger and be slowly cooked to death.

This is meant to illustrate people’s inability or unwillingness to react to or be aware of sinister threats manifesting steadily.

The US Congressional Budget Office projects federal debt to reach $50 trillion in the next 10 years.

- 10 shares to give you a £10,000 annual income in 2024

- Where to invest in Q1 2024? Four experts have their say

One estimate is for US interest payments of over $13 trillion in respect of the next 10 years. Politicians will doubtless differ as to how this is to be managed; for example, and comparably in the UK under Truss, “go for growth” which we also tend to hear from Labour.

But now the inflation genie is out the bottle, unless it soon meets central bank targets of 2%, they are going to push back against growth by keeping interest rates high.

Chance of major risk aversion in financial markets

This is the key question, where examples such as the Latin American debt crisis in the early 1980s, and initial fears over the US manifesting as it borrowed to revive growth post the 2008 crisis, actually proved major buying opportunities in equities.

It is impossible to predict with any reasonable assurance what might be the US path to manage its debts, or indeed elsewhere as the EU for example secures a £42 billion equivalent aid package to Ukraine. Much of this “global debt” matter will relate to security demands, and it’s unclear how much additional defence commitment will be required.

The only thing to say with surety, is that holders of US assets – indeed elsewhere – be steeled for volatility, and to take advantage thereof.

Edmond Jackson is a freelance contributor and not a direct employee of interactive investor.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.