Value investing: How to become a bargain-hunter investor

We look under the contrarian bonnet at value fund managers hunting for bargain shares.

20th September 2019 16:18

by Tom Bailey from interactive investor

Value fund managers adopt many different approaches in their hunt for bargain shares, so we look under the contrarian bonnet to see which works best.

The basis of value investing involves buying a stock for less than it is (or should be) worth and holding it until the market catches up and re-rates: "buy low, sell high", as the cliché goes. But in recent years markets have behaved slightly differently, and the more rewarding method of investing has been to go for so-called growth stocks. These are companies that are highly valued in anticipation of future growth. "Buy high and sell even higher," has instead been the mantra.

Take the Russell 1000 Value index – an index composed of the 1000 largest US companies deemed to be cheap as measured by the price-to-book ratio (see jargon-buster below). Had you invested £100 in the index 10 years ago, you would have seen gains of roughly 300%, giving you a total of £400. Not bad.

Will value investing return?

Those returns, however, were below those of the regular Russell 1000 index, which saw gains of 372%, meaning that £100 could have been turned into £472. Even more frustrating for any value investor, opting for the Russell 1000 Growth index would have seen £100 turned into £550, a 450% increase.

In short, value has underperformed. The reasons behind this are many; chiefly, however, low interest rates have made richly valued growth stocks more alluring, as the expected future earnings of such companies when measured against the low cost of borrowing look more attractive.

When these conditions will change is unknown. Since at least 2016 there have been regular predictions of value investing's comeback, as the US continued to tighten monetary policy. But since the start of this year the US central bank, the Federal Reserve, has changed course, meaning we can expect the world of low interest rates to continue for the time being.

At the same time, there has been some speculation that value investing itself is broken. In our service- and tech sector-dominated modern economy, the argument goes, the traditional measure of value is no longer helpful. The value of intangible assets such as brand power or algorithms are not fully captured in financial statements.

While there may be some merit to that argument, similar criticisms of value investing were made in the late 1990s, just as growth stocks were soaring to new highs as part of the dotcom bubble.

Indeed, one of the only constants in finance has historically been the ability of a value approach to produce good results for investors. As a 2017 study by Vanguard showed, by far the most reliable predictor of returns is a low price-to-earnings ratio, a key metric for many value investors.

At the same time, study after study has shown that value stocks outperform growth – the exception being during certain bull markets, as is the case right now. But all bull markets come to an end, and with them the outperformance of growth.

Don't be left naked when the tide shifts

As Sven Carlin writes in Modern Value Investing, "There hasn't been much benefit in being a value investor in recent years, as a rising tide lifts all boats." But, he continues:

"The point of value investing is not to leave you naked when the tide shifts… being a value investor now can provide the necessary protection to minimise your losses and increase your returns when the next bear market comes. And a bear market always comes."

At the same time, despite value in general doing poorly, there are many different types of value investing and some value-focused funds that have still been able to provide opportunities for profit, even when value as a whole has been out of favour. Indices such as the Russell 1000 Value index often use simple metrics to identify value. In the Russell 1000's case, it is price-to-book value. Other investors approach value in different ways.

The first investor to attempt to apply rigour to value investing was Benjamin Graham, who famously published The Intelligent Investor in 1949. Graham outlined several ways an investor could judge a stock to be trading at a price below its supposed intrinsic value. This included finding companies whose shares were selling for less than half of what they held in cash – "buying a dollar for 50 cents," as he referred to it. Other rules included not paying more than 10 times a company's earnings (price-to-earnings) and selling out once a holding had gone up 50%.

While some of Graham's methods of valuation and rules (such as selling if a stock goes nowhere in two years) have been discarded by many value investors, his work remains the theoretical foundation of value investing.

Strong companies, good value

Graham's most diligent student was Warren Buffett, now the world's most famous value investor. Buffett's major change from Graham's approach was a greater emphasis on company quality. Many of Graham's selections were not actually value buys but cheap companies on their way to going bust.

So while Buffett still attempted to find underpriced companies, he also looked for those with superior internal economics. Chiefly, this meant finding firms with a strong and enduring competitive advantage and high margins, and holding for the long term.

One investor in the UK faithfully following Buffett's approach is Keith Ashworth-Lord, who manages the CFP SDL UK Buffettology fund. The fund attempts to replicate Buffett's approach to investing, finding quality companies with strong competitive advantages that are deemed good value.

As with Buffett's own approach, this emphasis on quality often causes confusion, as it is seen to be at odds with value. But the basis of both strategies is finding high-quality companies on a relatively low valuation, rather than paying high prices for future potential growth, as is often the case for growth investors.

Long-term recovery

At the other end of the value investing spectrum is the so-called cigar-butt technique, another phrase coined by Graham. The basic idea is to find companies that, while potentially in decline, have been priced so low by the market that the share price provides a one-off return as the gap between the business's price and its true value narrows. So long as the company doesn't end up completely collapsing, it should provide a puff of profit for cheap, just like a discarded cigar butt someone may find.

This is somewhat similar to the approach of Alastair Mundy, the famed manager of Temple Bar Investment trust (LSE:TMPL). Mundy says: "We describe our process of stock selection as rifling through other people's dustbins." He continues: "We scour the market for unloved, misunderstood or forgotten stocks – companies which have fallen 50% versus the benchmark, and where our analysis suggests there is considerable fundamental value."

However, unlike many followers of cigar-butt investing, Mundy has a fairly long time horizon for recovery. He says:

"We are not looking for companies that are going to shoot the lights out in the short term, but rather those which are very good value and have the potential for long-term recovery and improvement. Unlike many funds, we are very patient and we are prepared to wait."

Currently, Mundy has his hopes pinned on UK banks. "They have become something of a pariah sector and they remain on undemanding valuations, yet we have seen significant changes and improvements over the past decade," he argues. "New management, better balance sheets, improved regulation and the payment of fines have led to them becoming profitable institutions."

Positive change in the pipeline

Another successful UK value investor is Alex Wright, manager of Fidelity Special Values (LSE:FSV). He describes his approach to value as being based on buying unloved companies undergoing positive change and holding them until their potential value is recognised by the wider market.

Wright says:

"All value investors look for 'cheap' stocks. However, I only invest where I see an opportunity for positive change that would lead to other investors re-evaluating the company and buying back into the shares. We want to understand exactly what will lead to the shares not staying 'cheap' forever."

Wright also points out that he only looks at companies where he believes he understands the downside risk, limiting the potential for losses.

Other investors have attempted to come up with more elaborate ways to find value. For example, Tony Yarrow, co-manager of the TB Wise Multi-Asset Income fund, says that he makes use of an imaginary 'alarm clock' (see illustration). Stocks at the top of the clock face are those deemed fashionable and therefore expensive and should be avoided by value investors.

The rest of the clock face is divided into five overlapping sections, 'still falling', covering from when he buys up to 6pm, 'bottoming out', (5.30pm to 7pm), 'early stage recovery' (6.30 to 8.30pm), 'sweet-spot recovery' (8pm to 10pm) and finally 'fully valued' (or ‘the departure lounge'); the aim is to sell before midnight.

Yarrow says his team attempts to complete its research process on a stock before the price falls to four or five o'clock, which is when the clock's alarm goes off and he starts to buy. He continues:

"Ideally, we'd buy everything at exactly six o'clock, the lowest point before the price starts rising, but because such perfect timing isn't possible in practice, we are more likely to move to an appropriate weighting over the course of a few weeks or months."

Value funds favoured by financial experts

Ben Yearsley, director of Shore Financial Planning, says Schroder Global Recovery is one of his favoured value funds. "The managers prefer stocks on a discount to their asset value, rather than a company on 15 times price to earnings, growing at 15% a year, as predicting the future growth is unpredictable." Contrary to the Buffett approach, the Schroder team are not trying to buy cheap quality but are "buying cheap to intrinsic value."

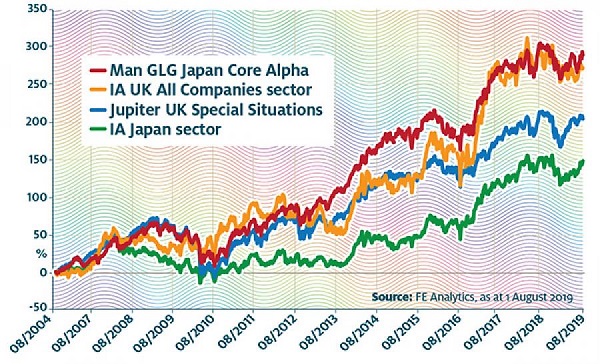

Another of Yearsley's picks is Man GLG Japan CoreAlpha. He says:

"The managers are contrarians. They want to buy stuff that's underperformed, so are looking for low price to book and high dividend yield. Companies also need enough financial strength to recover."

Juliet Schooling Latter, research director at FundCalibre, points to Jupiter UK Special Situations. “Manager Ben Whitmore is basically a contrarian investor who buys lowpriced shares in companies that are well-run, or have the potential to be well-run,” she says.

Contrarian view pays off over 15 years

Watch out for value traps

Sometimes, no catalyst for a revaluation by the market appears. As a consequence, investors may find themselves holding a potential 'value trap'. There are several ways to attempt to avoid this.

Graham's method of selling after two years may help. This problem, however, is that you are also likely to sell out of shares that are simply taking longer than expected to recover. But as is often said, the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain insolvent.

Another option is to ensure the company actually has strong fundamentals, such as balance sheet strength. This requires in-depth knowledge of the business and its financial statements, and also of the industry in which it operates.

Investors can also minimise risk by ensuring a margin of safety, a key idea in value investing. This means only buying shares when their market price is significantly below their intrinsic value. This explains Mundy's rule of considering a share when it has fallen 50% from the benchmark.

Jargon box

Price-to-book: This measures the market price per share against the book value per share. Book value is the net asset value of a company according to its balance sheet. A PB of below 1 suggests an investor is buying the company for less than the underlying assets are worth.

Price-to-earnings: PE is the ratio of market price of a share compared to the company's earnings per share. A high P/E would suggest the market believes the business has strong growth prospects, a low P/E the opposite. Value investors seek companies mistakenly placed on a low PE by the market.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.