The Analyst: navigating the fund fees dilemma

Fees can significantly impact portfolio performance, something which many investors often overlook. Analyst Dzmitry Lipski explains the range of fee structures and what to consider when buying a fund.

10th June 2025 09:09

by Dzmitry Lipski from interactive investor

Investors considering a fund for their portfolio should not underestimate the importance of analysing the fund's fee. Fees can significantly impact a portfolio’s performance and, in turn, affect long-term returns. Since fund fees vary widely and are often charged in different ways, understanding them is essential for making informed investment decisions.

- Invest with ii: Buy Global Funds | Top Investment Funds | Open a Trading Account

Investors aim to achieve returns that outweigh costs, but high fees, especially when compounded over time, can erode gains. For instance, two funds with similar performance may deliver very different net returns if one charges significantly higher fees.

Over the long run, even small differences in fees can lead to substantial differences in net returns. In addition, investors want transparency and clarity regarding the fees they pay. Investors expect a clear and comprehensive breakdown of all fees, including management, performance, and other charges. Complex or hidden fees can be a red flag and may ultimately influence the decision to invest in a particular fund.

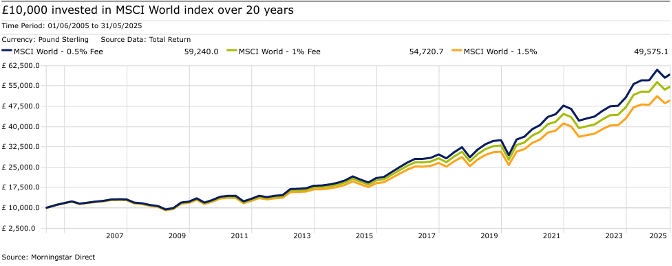

The chart below shows that £10,000 invested in global equities two decades ago would be worth £59,240 today if you paid an annual fee of 0.5%. But the return falls to £54,721 if the fee increases to 1% and shrinks to just £49,575 if you’d paid 1.5%.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

Key fund fees components

A fund’s fee structure typically consists of the following components:

The ongoing charge figure (OCF) is probably most common for investors. It includes various expenses such as the annual management charge (AMC), audit, regulatory and other administrative fees. The AMC is usually the most significant cost associated with investing in a fund and is generally based on the fund's size. When selecting a fund, the objective should generally be for the OCF to represent good value for money and not be significantly higher than its peer group average. Exceptions may be made for highly specialised or niche funds.

The transaction costs are incurred when buying and selling securities within the fund. This includes broker commissions, entry and exit charges, spreads, stamp duty, transactions tax, and foreign exchange costs. These costs will all contribute to the overall cost of investing in a particular fund.

Some funds charge performance fees, which are typically a percentage of any returns that exceed a predefined benchmark or threshold, in theory incentivising outperformance. These are considered incidental costs and usually apply only when the fund outperforms its targets.

The total fund costs figure combines the ongoing charges, transaction costs, and any incidental fees such as performance fees. It represents the total expected cost of investing in the fund.

Various fund fees structures

Over the past decade, fund fees have been falling, prompting fund managers to continuously evolve their fee structures. Managers now adopt a variety of models, with flat fees still the most common. Tiered fees, particularly popular in the investment trust sector, and performance-based fees or combinations of those are also widely used. Some managers even waive fees during periods of underperformance to maintain investor confidence.

In contrast, many investors remain reluctant to adjust their portfolio holdings despite changes in fee structure and market conditions. For example, some have remained invested in the popular Fundsmith Equityfund, despite it charging above-average fees for many years. They may be hesitant to switch to lower-fee active funds because they've been with their current fund for years and still believe in the manager’s skill.

Investment trusts have increasingly adopted tiered fee structures, where the annual charge decreases as assets under management grow. This approach passes on economies of scale to shareholders in the form of lower fees. A notable early adopter of this model was the Scottish Mortgage Ord (LSE:SMT)Investment Trust.

Although performance fees are becoming less common among retail funds, there is an argument that a fee that increases with performance helps align managers’ interests with those of the investors. There are still a range of performance fees used within the industry. Investors favour those which mean the fund manager must recoup any losses back to a high watermark before they start to generate a performance fee. A model used in some countries, including the US and Norway, is “fulcrum fees”, where a performance fee is payable if a fund outperforms, but reduces by an equal amount if it underperforms. This could be viewed as a fairer charging structure.

An example of this approach is the Orbis OEIC Global Balancedfund, a diversified global portfolio. It charges a performance fee equal to 40% of the fund’s outperformance relative to its benchmark, which is refundable at the same rate in the event of future underperformance.

Fees for different investment strategies

The disparity in fees between various funds stems primarily from the strategies employed by fund managers.

In general, actively managed funds aim to outperform the market, as measured by specific benchmarks such as the FTSE 100 or S&P 500 indices. These funds rely on managers to research, select, and adjust portfolios to beat the market. This approach typically incurs higher fees due to the additional resources and expertise required.

Investors usually pay more for the expertise of an active fund manager. For instance, the average cost of an actively managed UK equity fund is around 0.85%. A specific example is Fidelity Special Values Ord (LSE:FSV)trust, which focuses on UK mid- and small-cap stocks and charges a fee of 0.7%.

- Watch our Fundamentals video: what does a fund manager do?

- Sign up to our free newsletter for investment ideas, latest news and award-winning analysis

While actively managed funds have the potential to deliver higher returns if the manager makes consistently good investment decisions, evidence suggests that many fail to outperform their benchmarks over the long term, unless there is some luck involved.

Therefore, it is essential to evaluate fees in the context of net returns, not just the headline cost. For example, if an actively managed equity fund charges 1% annually but consistently outperforms the market by 2% per year, the higher fee may be justified. In contrast, a passive S&P 500 ETF may charge just 0.05% but simply mirrors the market.

Without consistent outperformance, investors might be better served by low-cost passive funds. Alternatively, if an active fund with higher fees and a passive low fee fund deliver the same returns, the passive fund with lower fees will yield better net returns over time due to reduced fee drag.

In addition, active funds that frequently rebalance portfolios or make tactical shifts are costlier to run compared to passive funds, which aim to replicate the performance of an index with minimal trading. For example, a tracker fund investing in the FTSE 100 would usually cost less than 0.1%. Popular on the ii platform, the iShares Core FTSE 100 ETF GBP Acc GBP (LSE:CUKX), for example, has an ongoing charge of just 0.07%.

Funds tracking the US S&P 500 index can be even cheaper. TheSPDR S&P 500 ETF USD Acc GBP (LSE:SPXL), the cheapest in the market, charges only 0.03%. Some passive investments such as the SPDR S&P 500 ETF, can even lend stock they own for a fee that ultimately can offset the already low management costs investors are subject to.

Some investors claim that passive funds cannot protect investors from periods of volatility, unlike active managers who are flexible to adjust portfolios to minimise losses in a falling market. Actively managed funds charge higher management fees than passively managed funds but do not necessarily guarantee superior returns to investors. Over the last decade, actively managed funds on average fail to outperform low-cost passively managed funds.

- Active or passive: the ultimate guide to investing your ISA

- Watch our Fundamentals video: what is a passive fund and is this the best way to invest?

Ultimately, fund fees could be an important factor when selecting an investment strategy for your portfolio. Investors can use both active and passive strategies as a way of diversifying portfolios and minimising costs. Pick an active fund to gain exposure to more under-researched areas such as emerging markets, then use passive funds for more developed and efficient markets such as the US.

Other metrics to consider

In addition to AMC and OCF, which are the most used fee metrics, there are other important measures to consider when analysing fund charges.

It’s important to consider not only a fund’s returns but also the level of risk taken to achieve those returns. Metrics such as the Sharpe ratio can be useful for comparing the risk-adjusted performance of different funds.

Active Share, which measures how much a fund's portfolio differs from its benchmark index, can also help justify higher fees. If a fund charges more but closely mimics the index, investors may question whether the higher cost offers real value.

To conclude

While fund fees can clearly have a substantial impact on returns to investors over the long run, it’s not just the numbers that matter, and investors should consider whether the strategy and expected returns justify the cost.

When picking a fund, fees should not be assessed in isolation. Instead, they should be evaluated alongside other portfolio metrics and over time. This helps investors understand how a fund's performance varies across different market environments and what returns they can realistically expect.

Additionally, comparing a fund’s fees with those of its peers can offer valuable insights. If a fund charges higher fees without delivering superior performance, investors may want to reconsider their allocation and potentially switch to a more cost-effective option.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.