The ESG Investing Handbook: your guide to understanding an evolving area

29th June 2022 11:16

by Rebecca O'Connor from interactive investor

With climate change and net-zero emission in the spotlight, this practical guide examines the latest thinking on environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing and addresses areas including pensions, greenwashing, financial performance, and making your money greener. Read an extract here.

The ESG Investing Handbook, written by interactive investor’s Head of Pensions and Savings, Becky O’Connor, is available to download for free at Harriman House.

The below extract is taken from the introduction.

One acronym too many?

It’s impossible to begin a book with an acronym in the title without an immediate definition. Although it is tempting to assume that everyone in the world now knows ‘ESG’ stands for Environmental, Social and Governance factors in the context of investment decision-making (this book was written only a few months after the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow), in fact it is not yet universally understood. Mention it at the dinner table with friends and you may be met with blank stares and, if lucky, some educated guesswork.

In a 2019 survey of private investors by Research in Finance, only a little over a tenth of respondents could correctly write out ESG in full.This figure could be slightly higher now, given the surge in interest in sustainability and the role of global finance in saving the planet in just three years. But it would be optimistic to imagine it much higher.

Despite this lack of knowledge of what ESG means, the amount of professionally managed portfolios that had integrated key elements of ESG assessments exceeded $17.5 trillion globally by 2020, according to the OECD.

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the UK’s own regulator, is now heavily focused on ESG, publishing its own definition in December 2021. The following excerpt from the report highlights the complexity of the terms involved:

“ESG and sustainability are hugely important. But terms such as ‘climate’, ‘environment’, ‘sustainable’ and ‘ESG’ are often used loosely across the financial sector; and sometimes interchangeably.

“There is of course an overlap between the terms. Climate change is a core focus of environmental work, which is itself one pillar of ESG. And ESG captures the key dimensions of wider sustainability; that is, how people, planet, prosperity and purpose come together to help enable ‘the needs of the present [to be met] without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (see the United Nations Our Common Future report). Values are embedded in ESG. But importantly, the scope of ESG is much wider.”

There is plenty of evidence that the concept, if not the acronym itself, is beginning to seep into the mainstream. The recent rise in popularity of investing with the planet and people in mind – as well as profit – is indisputable.

As the FCA’s own Financial Lives Survey 2020 found, almost two-thirds of participants reported that they worry about the state of the world and feel personally responsible for making a difference. Four out of five respondents consider environmental issues important and believe that businesses have a wider responsibility than simply to make a profit.

Two years ago, assets under management (AUM) in sustainable and ethical funds available in the UK stood at £103 billion. This had more than doubled to £280 billion by October 2021, according to the Good Investment Review conducted by Square Mile Research’s 3D Investing and Good With Money. The number of funds qualifying for inclusion in this universe rose from 264 to 348 between October 2019 and 2021 – a race for supply to meet growing demand.

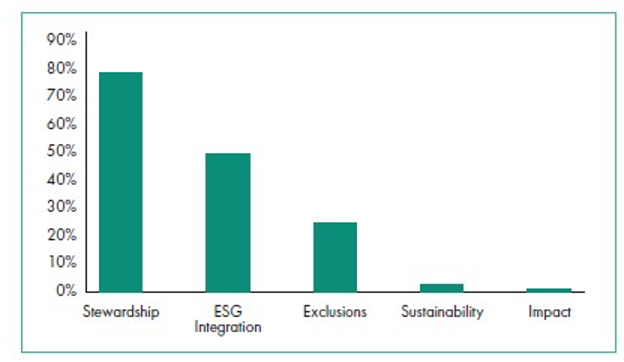

According to the UK Investment Association (IA), the majority (77%) of industry assets are now subject to ‘stewardship’ activity. The integration of ESG factors in investment decision making was present in 49% of investment approaches in 2020, up from 37% in 2019.

Among younger, millennial investors, there is evidence of a stronger desire to invest according to values than is found among the general UK investor population. Two-thirds of Generation Z and millennial investors consider a company’s goals, mission and purpose prior to investing, according to Equiniti. This will become increasingly relevant to the industry as this principled cohort matures, earns bigger salaries, possibly inherits money from baby boomer parents and then is faced with a choice over how to invest their growing wealth.

But in thinking about ESG as a generational concern, the danger is it becomes boxed in the category of ‘woke political agenda’. Larry Fink, chief executive and chairman of BlackRock, made an effort to get it out of this box in his 2022 CEO letter. He writes:

“Stakeholder capitalism is not about politics. It is not a social or ideological agenda. It is not ‘woke.’ It is capitalism, driven by mutually beneficial relationships between you and the employees, customers, suppliers, and communities your company relies on to prosper. This is the power of capitalism.”

Figure 1: Proportion of assets under management by responsible investment category (2020)

Source: Investment Association, IMS Report, 2021

The IA found that assets within sustainability-focused strategies have almost doubled from 1.4% of industry AUM to 2.6%. Impact investing remains more niche, with a small number of firms managing impact investment strategies, representing 0.5% of industry assets. Assets subject to exclusions also increased in 2020, reaching 25% of AUM, up from 18% in 2019.

But it is important to consider how these approaches can overlap and be practised at the same time by fund managers. To date, the industry has tended to view these approaches as distinct and discrete disciplines. In reality, even if a fund has one primary approach – impact, for instance – by definition it also practises exclusion (equating to negative screening and an ethical approach) and considers material risks (which are a component of ESG).

Increasingly, funds are applying a range of different approaches to this area. As John Fleetwood, founder of 3D Investing, highlights in the latest review, a number of multi-asset ESG funds have launched in recent months. He says:

“these are ‘all-in-one’ solutions, with each fund in the range being managed according to a given risk profile. These largely adopt a strategy of an element of ethical screening combined with an ESG tilt and a minority allocation to sustainable solutions.”

As ESG investment grows in popularity, choice and maturity, the debate over what to call it – a term that accurately reflects what it is, doesn’t allow for a loosening of the reins or inspire greenwash, and is still usable to lay people – rages on. The term ‘ESG’ arguably sits better within the investment industry that coined it than in the sphere of normal investors looking for somewhere to put their ISAs. More accessible terms such as ‘ethical’, ‘sustainable’, ‘responsible’ or ‘green’ may be more fit for wider use, even if they come with technical differences to investment practitioners. Acronyms inherently sound quite technical and scientific. But they are also useful at shortening what is quite a broad and sophisticated range of considerations and approaches – in this case into just three letters.

Every year millions more dollars are pumped into sustainable investments and the industry of analysts, NGOs and regulators that supports them. The race to become top dogs in the ESG asset management and ratings fields, to produce the finest metrics and to be the loudest voice, has pressed the buttons of those with keen radars for spin and bluster, who believe the whole exercise is no more than overzealous marketing of something that shouldn’t really be in the field of marketing.

Others take the view that if ESG is your selling point and you are good at it, then why not tell everyone? How else are you going to attract the money that wants to invest in quality ESG, unless you communicate it? But there’s saying and there’s doing, and the gap between the two is an area of increasing preoccupation for those trying to work out where to put their – or their customers’ – money, as well as for regulators.

Beyond risk and return: what ESG is – and isn’t

ESG stands for Environmental, Social and Governance factors, in the context of investment decision-making, usually (but not always) among asset managers – the companies charged with managing the money we all invest, one way or another, in our pensions and ISAs. It is also a way of measuring investee companies against these criteria – you can’t practise ESG as an investor if the companies you have the choice of investing in do not also reflect those values. So a company that wants to attract investors who have demanding ESG requirements has to have a good story to tell when it comes to ESG.

The approach is essentially applying a measuring tool for impacts not traditionally measured by the risk/return investment equation. It is a holistic attempt to quantify the sometimes elusive and often nebulous effects of a business activity. It’s a way to identify, measure and compare the positive and negative actions and externalities associated with an investment, whether that’s a company or an investment product, like a fund or an ETF.

Because it is a measuring tool, how it is measured, not just what it is measuring, is particularly important. This issue has become the subject of significant debate. Ratings systems for ESG are discussed in Chapter 6.

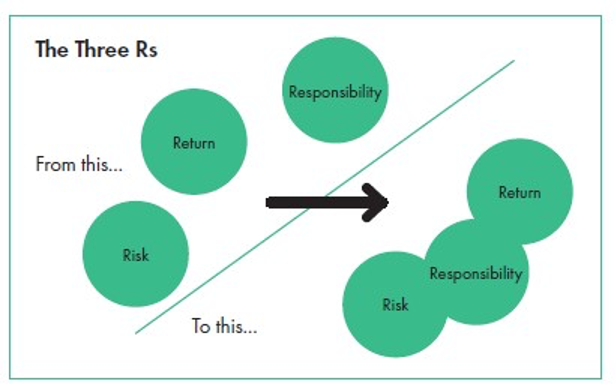

It is sometimes described as a third factor in investment decision-making – leading to the three Rs of ‘Risk, Return and Responsibility’. However, perhaps a more accurate way of thinking about it is that it permeates and fundamentally changes the risk and return calculations, particularly over the long term. This book examines the argument that ESG sits firmly within the category of risk management of investment firms and at investee companies in Chapter 3.

Figure 2: Risk, return and responsibility

ESG versus ethical

It’s tempting to use the terms ‘sustainable’ or ‘ethical’ instead of ‘ESG’. As a former financial journalist, I know that a technical acronym that has to be spelled out and takes up 36 characters is going to be met with an eye roll – it is not a good use of finite space. The problem is that the investment industry, when confronted with ‘ethical’ or ‘sustainable’ as bywords for ESG, eyerolls back. To the industry, ‘ethical’ refers to the negative screening of harmful activities and precedes ESG as an investment approach. The oldest ethical investment funds, which came to being before the immediacy of the climate crisis was well known, removed things like tobacco, arms manufacture and animal testing – activities that caused obvious harm to people or animals. Among the first modern funds of this type, the Pax fund was launched in 1971.

An ESG approach is not the same as this negative-screening, traditional ethical approach, even if the underlying concept of doing more good than harm is similar (although depending on your point of view, your drive to include ESG factors in your own investment decisions may be entirely ethically motivated). So ESG can be ethically driven, but it doesn’t have to be. It could just as easily be about minimising risk and protecting financial value over the long term. Whereas ethical investing does take into account ESG factors to varying degrees, depending on the specific ethical issues being addressed.

ESG versus CSR

CSR, or Corporate Social Responsibility (the third acronym to be mentioned in the introduction alone!) refers to companies giving money to charity, allowing employees to volunteer for good causes and generally trying to do some social good alongside their day-to-day business. It’s worth mentioning here as it’s a more established, charitable part of usually large businesses and has been confused with ESG in the past. However, they are not the same, as they try to do good in different ways and function in different parts of a business.

Traditionally, a company’s CSR efforts have had very little to do with its ESG standards relating to operations, supply chains, HR and so on. CSR has been a standalone area of the business, which (very cynically) stands accused of merely making bosses feel good about themselves to little genuine net positive effect, but (more favourably) can have a huge social impact if applied at scale throughout the business. Alex Edmans, professor of finance at London Business School, describes it critically thus:

“In the early Catholic Church, the wealthy could commit any number of sins and buy an ‘indulgence’, or earn one through good works, that absolved them from punishment. That’s similar to how CSR is often practiced. A company can undertake CSR without changing its core business; instead, it involves activities siloed in a CSR department, such as charitable contributions, done to offset the harm created by its core business.”

ESG is not CSR, and CSR activities – while good and laudable – should not sit in the basket of company activities to be measured for their ESG value. ESG lives traditionally in asset management, in the ‘where to invest’ decision-making function of a big investor. In order to be investible from an ESG perspective, it also has to live in every part of a company that wants to attract ESG-motivated shareholders, not just within the CSR section of an annual report.

ESG and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

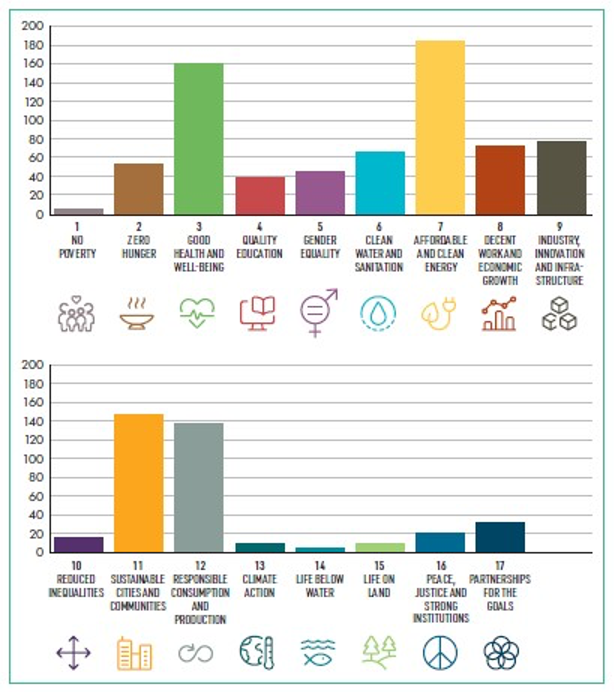

The big, global problems the world faces were carefully laid out in the 17 UN SDGs (another pesky acronym that stands for Sustainable Development Goals) back in 2017, and cover a range of focus areas.

The SDGs came to be used as a framework by which to measure sustainable development and have also been adopted by the investment fund industry as a way to steer itself on a better course.

The usefulness of the SDGs as a way to rate the ESG quotient of an investment is limited, however, as it may be possible to crowbar a company’s activities into one of the goals and claim victory, while ignoring or even doing harm relating to some of the other goals.

There are accusations of SDG-washing, and an asset manager’s assessment of how well they measure up against each SDG must sometimes be read with a pinch of salt.

Over time, it has become apparent that asset management is struggling to find ways to address some of the goals that lend themselves less well to profit-seeking solutions. According to Matthew Ayres of Ethical Screening, the UK-based consultancy, not all of the goals have proven genuinely investible to date. The table below shows which of the goals have attracted the most investment – and which goals asset managers have struggled to meet.

Figure 3: Which goals are investible? All goal hits across ethical screening database

Source: Ethical Screening

So, while using the SDGs as a way to frame and measure ESG progress can be useful, there is no official link between the two.

ESG versus green

The term ‘green’ is often used as shorthand for sustainable investments because it is simple and consumer friendly. But green only really refers to the ‘E’ part of ESG – it’s possible to have a green fund that doesn’t have any particular mandate or official duty towards good social outcomes or governance standards. You’d hope an investment that purported to be green would also meet these other standards, but whether it does or not is not necessarily set in stone if its focus is only on the planet.

Because it deals with social and governance standards too, ESG encompasses more than ‘green’ investing does. However, the urgency of climate change, COP26 and the need to control emissions and global temperature rises means that the green or environmental part of ESG has dominated column inches and arguably investors’ preoccupations recently. This urgent need to act, alongside the argument that environmental investment options are more mature and numerous than socially beneficial investment options, has given rise to a greater number of investment products in this area, as well as far greater focus on the ‘E’.

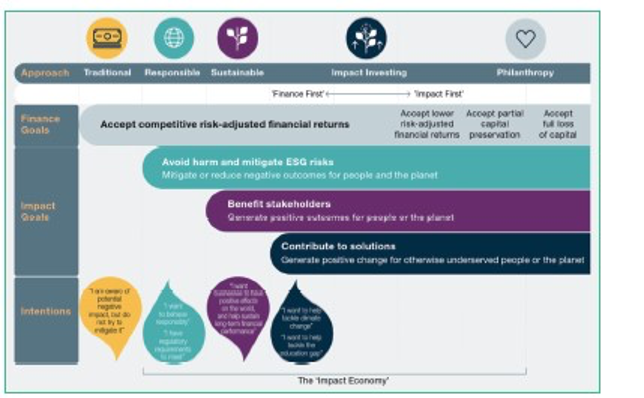

Figure 4: The spectrum of private capital

Source: Impact Investing Institute

Resolving (or not) the great terminology debate

This book is intended as a practical guide to understanding the rapidly evolving field of ESG investing. While the terminology and its application has caused difficulties and does seem at times a little too open to interpretation, it’s important to start by establishing the understanding of ESG that this book is working on.

While ESG attempts to make a part of the investment process that might otherwise be viewed as ‘moral overreach’ scientific, it’s hard to avoid taking a philosophical position on the definition. This goes back to what ESG was intended to do – rather than what it might have come to mean relative to other terms and in light of what the investment industry has done to it.

ESG may not exactly be the same as ethical investing, and yet there is overlap because both involve some degree of value judgment. ESG may be about measuring and internalising externalities, but the questions around whether we should care about measuring those externalities in the first place, and which to care about most, are moral ones.

It may also be worth considering the spirit of the term when deciding what it means or how well any investment is doing. Clearly, those who coined it felt that achieving all three elements within an investment was to some degree possible. Focusing solely on one element while giving little or no regard to the other parts of the equation would seem against this spirit of a general raising of standards and efforts to deal with these areas of potential harm or benefit holistically.

A shared understanding that investing involves the consideration of externalities – the benefits and harms to stakeholders other than shareholders – of a business or investment product, is essential. Unfortunately, such a shared understanding of the spirit of ESG is not a given. There are plenty of shareholders who do not believe that consideration of ESG is helpful either to financial returns or to the wider stakeholders: the planet, people, employees and customers whose interests ESG aims to represent.

For the purposes of this book, and at the risk of raising hackles, I use ESG as a catch-all term for investments that to some degree and in different ways – with different emphases between the three themes – consider environmental, social and governance factors. That is, a very broad and literal definition of ESG, which also includes negative-screening (traditional ethical), sustainability (focused on environmental but also social and governance), responsible stewardship and positive impact.

This is in the spirit of how the term was originally coined, rather than what it might have come to mean and some of the negative connotations it now has (for instance, the criticism that it has given rise to greenwash). Some of the problems the ESG approach has caused will also be covered.

The beginnings of an ESG backlash

Within the industry and among investors interested in this rapidly evolving area, ESG is causing divisions. Why has something which seems so innocuous become controversial? Accusations abound that the practice of merely ‘considering’ ESG factors is too vague, too forgiving, too easy to apply to investments that wouldn’t match any fair-minded person’s understanding of good for the planet or people. Even industry insiders tell how the term has been used and abused as a label that suggests an investment fund or trust is better than it really is; that there isn’t enough transparency over data to make genuinely meaningful ESG ratings. In an excoriating essay published last year, Tariq Fancy, former head of sustainability at BlackRock Asset Management, which moves almost $10trn around the global economy every day, characterised the way ESG investment is being practised as follows: “denial, loose half-measures, or overly rosy forecasts lulls us into a false sense of security, eventually prolonging and worsening the crisis.”

His words, a reflection of his experience at BlackRock, provided an opportunity for soul-searching within the industry. Unfortunately, they also provided ballast to those who view ESG as a distracting sideshow or simply a giant hoodwink among marketing departments that undermines the whole effort.

In January 2022 Terry Smith, the fund manager, blamed the distraction of corporate purpose work for Unilever’s decline in value over the year. “A company which feels it has to define the purpose of Hellmann’s mayonnaise has in our view clearly lost the plot”, he said in his annual letter to investors.

It may be true that there is room for wasteful investments as part of an ESG agenda. As Alex Edmans, professor of finance at London Business School, says in his book Grow The Pie, “A source of wasteful investment is supporting social causes that either are unrelated to a company’s comparative advantage or create distraction from the core business”; however this does not necessarily have to unravel the whole endeavour.

ESG has its detractors on both sides – among the fundamentally cynical and those absolutely committed to environmental and social causes. As a result of some arguably misusing the term to overstate their case, discussing ESG has become almost shameful in some quarters of the values-based investment industry, particularly among those who favour positive-impact, solutions-based investment strategies. There is a view that ESG is far too wishy-washy and forgiving – its original purpose now diluted and worse, manipulated, to sugarcoat the status quo. Some have now seen so much misuse and misinterpretation of ESG that the negative connotations of the term have superseded any positive intentions it once had, to the extent that anything with the label should now actively be avoided by anyone wanting their investments to do genuine good.

And so ESG has become a dirty term among some positive impact purists and has been placed right at the very heart of why ‘greenwash’ – the misleading marketing of investments that do not help the environment as ‘green’ – has become a risk to the entire enterprise, which could cause a wholesale lack of confidence in the effort to think beyond risk and return.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.