How to invest using ETFs: a beginner's guide

We look at the nuts and bolts of ETFs, what they aim to achieve and how they have developed.

5th June 2019 11:05

by Kyle Caldwell from interactive investor

We look at the nuts and bolts of ETFs, what they aim to achieve and how they have become more sophisticated and nuanced.

Exchange traded funds (ETFs) may not be quite the newest kids on the block, but they are certainly experiencing a growth spurt.

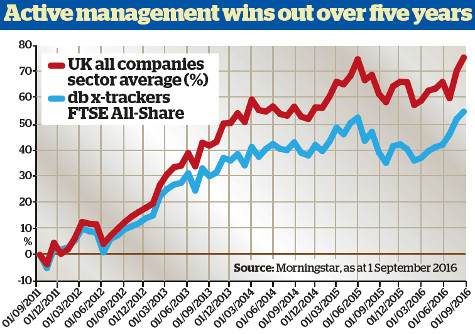

An increasing focus on the cost of investing and disillusionment with the performance of active managers, plus greater choice, have buoyed the popularity of the ETF sector. Investors are increasingly sold on the apparent charms of this cheap and diversified solution to stock market exposure.

ETFs came to the UK from the US in 2000: index trackers already existed, but passive was not the broad church it is today.

Invest with ii: Top Investment Funds | Index Tracker Funds | FTSE Tracker Funds

It was still common, for example, for providers to charge 1% for tracking the FTSE 100, a figure almost unheard of today. Passives were only available on a limited range of indices and comprised, at best, a niche part of the investment management industry.

The first ETFs on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) didn't look very different from the original tracker funds. They were based on large mainstream indices such as the FTSE 100 or S&P 500.

However, they did have some revolutionary qualities - they were traded on a stock exchange, allowing moment-to-moment pricing and liquidity, and they were cheap.

ETF structure

A key factor was that, in spite of being exchange-traded, ETFs were open-ended. This meant that they would always trade near to the asset value of the underlying shares.

Thus, they offered the advantages of exchange-traded securities - immediate pricing and transparency - but without any of the bothersome discount/premium calculations that can dog products such as investment trusts.

There were also important nuances that would appear later. As ETFs traded like a stock, it was possible to use them to go short - in other words, to bet that the index in question would fall.

They could also be used to hold futures and options, which was important in the development of exchange-traded products based on commodities such as gold or oil.

The first ETFs largely used 'physical' replication to match the performance of the index. That meant they bought a small chunk of shares in exact proportion to their allocation in the index. In this way, if BP (LSE:BP.) constituted 8% of the index, the ETF would hold 8% of its assets directly in BP shares, rebalancing over time.

Later, the investment banks became involved, introducing - perhaps unsurprisingly - greater complexity. Rather than using physical replication to match the index, they used derivatives.

This was fine until the financial crisis of 2008 introduced investors to the concept of counterparty risk. In other words, if the investment bank issuing the derivative went bust, what happened to the investors in the ETF?

It turned out that they would get the collateral that had been set aside, but that collateral was sometimes quite different from investor expectations, for example involving bonds instead of stocks.

This debate has meant that, to some extent, physical replication has won the day; all the major providers in Europe - iShares, Vanguard, HSBC (LSE:HSBA) - use physical replication.

Coverage

The real change has been in the sheer number of ETFs offered. There are now ETFs for a wide range of stock market indices and commodities; there are also fixed income ETFs.

The scope of ETFs has also broadened as a consequence of this expansion, with the emergence of some highly niche investment strategies: the London Stock Exchange lists ETFs investing in everything from the Bangladesh stock market, to consumer stocks, to long-dated government bonds.

There are a number of short and leveraged ETFs. In other words, if an investor wants to take a huge bet on the Footsie falling, she can do it through ETFs.

There are limits: the underlying investment must have sufficient liquidity, which has largely ruled out areas such as bricks and mortar property, but investment options are now extremely wide.

The latest innovation has been in the area of 'smart beta' or 'alternative indexation' ETFs. These aim to replicate indices that are not weighted by the size of the companies, as most are, but instead use alternative measures such as dividends, volatility or earnings growth.

Charles Aram, head of EMEA at Research Affiliates, says:

"These strategies systemise something, removing the need for an active manager at the helm. This can give investors an "active-like" portfolio at reduced cost."

'Factor'-based ETFs - a type of smart beta ETF - are also entering the mainstream: at the end of last year, passive giant Vanguard launched four new global factor investing ETFs, based on value, liquidity, momentum and low volatility return premiums.

In particular, volatility strategies have proved popular with investors keen to insulate themselves against the worst gyrations of financial markets.

These ETFs, for example the SPDR® S&P 500 Low Volatility ETF (LSE:USLV), iShares Core MSCI World Minimum Volatility ETF (LSE:SWDA) and iShares Edge S&P 500 Minimum Volatility ETF (LSE:MVUS), look at historic volatility levels of individual shares and weight their portfolios accordingly.

These have been very strong performers as investors have favoured larger, safer stocks with predictable earnings and cash flow.

Nevertheless, in spite of all these options, it should be said that most investors still plump for the plain vanilla ETFs.

Mark Fitzgerald, head of product, Europe, at Vanguard says: "These new options are not suitable for all investors. Some are really quite niche. When we look at where the bulk of assets sit, 90% or more are in the large, highly diversified traditional indices - the DAX, S&P 500, MSCI Europe, or FTSE All-Share. They are plain vanilla, building-block options."

Cost

One way in which the proliferation of ETFs has had an impact for investors is in regard to cost. There has been a race to the bottom on costs, as more providers have entered the market and competition has heated up.

A lot of the ETFs based on mainstream indices now charge less than 0.1% for ongoing management.

Although the cost structures for investors are different - they may have to pay an upfront brokerage fee as they would when buying normal shares - ETFs are now often the cheapest way to get diversified access to the stock market.

ETFs have come a long way, but in spite of all their bells and whistles, most investors still use them for cheap access to mainstream indices. It may be a little time before investors are emboldened to try a 3x leveraged oil ETF, or the smart beta alternative to active funds.

ETFs versus standard passive funds

There are several key differences:

Cost

The importance of cost as a factor in long-term returns is increasingly well-understood by investors.

And ETFs are undoubtedly low-cost. Costs for standard passive funds will be lower, but ETFs still tend to have the edge.

Fees

ETFs are traded like a normal share, so may be subject to a brokerage fee. This can be important for those making regular savings.

Investors also need to look at the spread between the buying and selling price, though for most ETFs these are very small.

Immediate trading

With a standard passive fund, when an investor puts in a sell or buy order, it is not transacted immediately. As the market can shift in the short term, investors therefore don't know the exact price they will receive. ETFs trade throughout the day, so offer more transparency of pricing.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.