Stockwatch: the outlook for UK shares amid recession warning

5th August 2022 12:04

by Edmond Jackson from interactive investor

The case for a hard financial landing is gathering force, says companies analysts Edmond Jackson, but better prospects for equities may be on the horizon.

Before the Bank of England dropped yesterday’s bombshell, I had drafted this as today’s introduction: “For investment decisions, so much currently hinges on whether a shallow short-lived recession follows - or something worse.”

I had also noted stubborn stagflation – my base-case scenario – would raise the risk of a debt crisis.

Well, 13% inflation in October as predicted by our central bank, with think-tank the Resolution Foundation predicting 15% by the start of 2023, with five consecutive quarters of recession, certainly defines stagflation.

- Find out about: Trading Account | Share prices today | Top UK shares

Does an optimistic case for equities really hold?

While the FTSE 100 index – with various internationally driven firms – is up 5% over the last 12 months, the FTSE 250 index is down around 20% given greater exposure to the domestic economy. Risk-aversion towards small-caps has meant a circa 30% decline in the AIM index.

Various domestic equities do now offer modest valuations and a material yield, which prices in some extent of the economic slowdown; but for those more cyclically exposed, is that enough for five quarters?

Bulls have nevertheless asserted “buy amid current gloomy sentiment” and to maintain any regular investing plan, drip-feed money into equities.

Energy price rises are hurting but it is said that this will help take excess demand out of the global economy after governments and central banks overdid stimulus measures in response to Covid.

- Stockwatch: buy the drop at this FTSE 100 dividend share

- Shares for the future: our own Warren Buffett names 23 shares in his ‘buy’ zone

In 2023, central banks will more likely be cutting interest rates once again.

Additionally, US second-quarter corporate earnings look pretty resilient – considering the extent of multinationals suffering from a strong US dollar when overseas earnings are translated.

We are not going to see anything like the US federal funds rates of 11% during 1979 and a peak of 20% mid-1981 when Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker stamped on inflation - there is simply too much debt.

Such is the broad case for buying equities sooner rather than later.

Why chronic stagflation is a realistic scenario

Yes, that subheading was also written before the Bank of England’s shocker.

I believe that it is wrong to assert that a reduction in economic demand will curtail inflation because there are too many “supply-side” factors making it unlikely to go away.

This began with supply chain disruption during Covid lockdowns when monetary and fiscal stimulus overcooked demand for the system to cope.

Russia then delivered its own version of Saudi Arabia halting oil exports in 1973, where Europe is ill-adapted to find alternatives to Russian gas.

Wage awards are ratcheting up after labour shortages in construction, transport and distribution had an initial supply-side effect.

And China’s zero-Covid tolerance policy raises the odds of further disruption to goods.

Whatever central banks do with interest rates, these supply-side constraints will stick for a while.

Now that double-digit UK inflation is the consensus for early 2023 at least, utilities and other businesses will benchmark it for next year’s billing.

The Bank of England has therefore lost the plot, allowing inflation to get ingrained.

Not dissimilar to the UK in the 1970s

The 1972 budget by chancellor Anthony Barber was designed to win an election in 1973 or 1974 – but the ensuing “Barber Boom” led to high inflation and public sector wage demands.

Present calls for tax cuts to stimulate demand miss the point in how supply-side issues are more vital, hence giving people more cash will not mitigate inflation.

Later in 1973, an OPEC-led by Saudi Arabia halted oil exports to nations that had supported Israel in the Yom Kippur war – and the resulting supply shock trebled oil prices.

Yes, oil prices are easing but gas continues to soar, with Russian supply disconnecting dealing Germany a crippling blow this winter.

- Interest rate hike: what does it mean for your savings, mortgage and investments?

- The investment lessons from the 1970s as inflation soars and rates rise

In late 1972, pundits had reckoned on the Dow Jones Industrial Average building on a 15% annual advance, but over the next two years it plunged 45%. The UK FT 30 index fared far worse, down 73% due to the “secondary banking crisis” where the Bank of England had to bail out banks exposed to property as asset prices fell.

Note how UK equities doubled after that slump; but the 1970s were typified by stagflation as inflation reached 25% in 1975.

Such history is a useful reminder of how reckless monetary and fiscal policies sow the seeds of inflation, and much supply-side constraint then ingrains.

As central banks now tighten monetary policy in unity, the ongoing constraints risk global recession.

Fifty years on, the extent of debt adds to financial risks

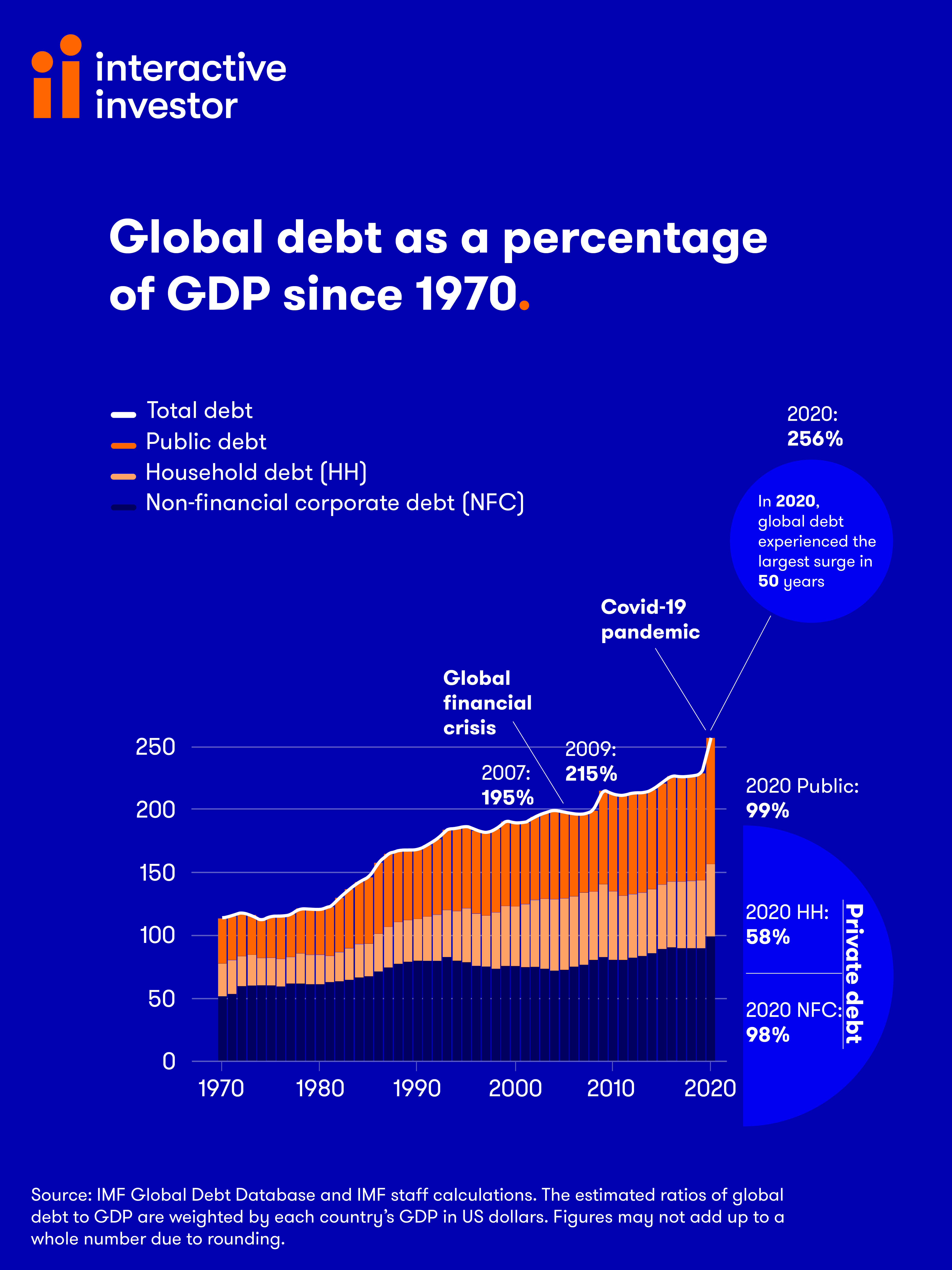

As a share of global GDP, private and public debt levels have advanced in near-linear fashion since the 1970s – over 250% by 2020 and some economists think more than 300% today, given a particularly sharp rise with the pandemic.

Consequently, the first real attempt to raise interest rates for decades is liable to push over-indebted households, companies and governments into default.

Yes, central banks would then be more likely to cut rates, if leaving inflation ingrained.

It implies volatility for equities, but you should have an extent of asset exposure versus cash value eroding; why I have made the case for industries with relative freedom to price, such as British American Tobacco (LSE:BATS) and drugs group AstraZeneca (LSE:AZN).

Public finance challenges compounded by excess QE

Central banks’ over-indulging quantitative easing (QE) in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis then again from spring 2020 has made nations more exposed to interest rate rises.

For example, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) estimates that the Bank of England bought back £895 billion worth of bonds representing 36% of GDP.

- Lenders in focus after Bank’s stagflation warning

- Share Sleuth: with three firms to choose from, here’s the one I bought

It has meant the Treasury benefited from some £120 billion remittances from the Asset Purchasing Facility (subsidiary of the Bank of England) as it profited, while interest rates fell (pushing bond prices up). But now rates are rising and bonds falling the NIESR estimates unrealised losses are already nearly as large as past gains.

Managing all this going forwards – with different maturities involved and a reversal of QE increasing – will need co-operation between the Bank of England and Treasury.

Risks to equities imply no hurry to buy

Decide for yourself, but I find the bull case for equities currently appearing flimsy, versus greater downside risks.

A silver lining could come via a ceasefire in Ukraine this autumn; quite whether that would prove permanent or a chance for Russia to recalibrate is another matter.

And yes, there will be special situations as equities get oversold or surprise on the upside, like we have just seen with Frasers Group (LSE:FRAS). Private equity is not going away, and takeovers may increase.

Gloomy though it may be on the economic front, the next 12 months should hold better prospects – for seizing genuinely attractive risk/reward in equities – than during the candy-floss years of monetary stimulus.

Edmond Jackson is a freelance contributor and not a direct employee of interactive investor.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.