BRICs: is the famous investment acronym no longer fit for purpose?

11th May 2022 10:21

by David Prosser from interactive investor

Two decades after the four countries were tipped for big returns the investment phenomenon’s attractions have slowly evaporated, reports David Prosser.

It has become one of the investment phenomenons of our time, but two decades after the world discovered the BRIC nations, is the acronym still fit for purpose? Brazil, Russia, India and China are all now in a very different place to where they stood in 2001, when Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill first grouped them as the BRICs – and a very different place to one another.

First, a short history lesson. O’Neill’s original work on the BRICs was primarily a call for a rethink of the world’s economic governance processes. He argued that the rise of these economies meant they should join an expanded version of the G7 group of countries that work together on key economic and political issues. The BRICs, individually and collectively, were already of a scale that matched the G7 members, O’Neill pointed out. And with their large populations and relatively low productivity, there was scope for them to accelerate at a far more rapid rate.

On its central argument, O’Neill’s call continues to fall on deaf ears. The G7 remains exactly that – and the BRICs have pursued collaborations of their own. However, investors seized on the implications of O’Neill’s work. If these slumbering giants were poised to close the gap on the advanced economies of the West, they reasoned, the potential for outsized investment returns was exciting. Investors have flocked to the BRICs – and funds offering exposure to them.

Successful first decade, followed by disappointment

They were not disappointed. Between 2001 and 2011, the first decade after O’Neill’s work, Brazilian equities delivered an average annual return of almost 22%, Indian and Russian equities gained 18% and 17% a year respectively, while China was up 13% a year. By contrast, the MSCI World Index offered annualised returns of just 3% over the same period.

- Investing in China: buying opportunity or not worth the risk?

- Three pros on why China’s political risk is a price worth paying

- Why I’d still buy Chinese stocks despite crackdowns

The subsequent decade was less impressive, with Brazil in particular holding the BRICs back. Nevertheless, over the 20 years following O’Neill’s paper, all four BRIC markets generated significantly better returns for investors than world markets as a whole. “It is closer than you might have imagined after the first 10 years,” says Nick Wood, head of fund research at the wealth management group Quilter. “But over the last 20 years, you would still have done better following Jim O’Neill’s advice.”

So much for the past – where do we go from here? Well, the first point to make is that the BRIC nations retain their most obvious advantages.

These are large nations that account for around 40% of the world’s population, 25% of its land surface and 25% of global economic output. It would take a brave investor to look past those numbers. Economists, moreover, expect them to continue to grow more rapidly: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts 4.8% and 4.7% average growth from emerging economies in 2022 and 2023 respectively, against 3.9% and 2.6% in advanced economies.

Against that, the case for looking at the BRICs as a distinct grouping looks increasingly weak. Most strikingly, few investors will currently want any exposure to Russia at all, whether their motivations are moral or mercantile. Until the crisis in Ukraine is resolved, Russia will play no part in investors’ debate about the merits of the BRICs.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

The rise of Asia and fall of Latin America

In truth, even before Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Russia had fallen from favour with investors; its economy’s dependence on commodities – oil and gas in particular – has left it unable to capitalise on economic opportunities given the volatility of the commodity cycle.

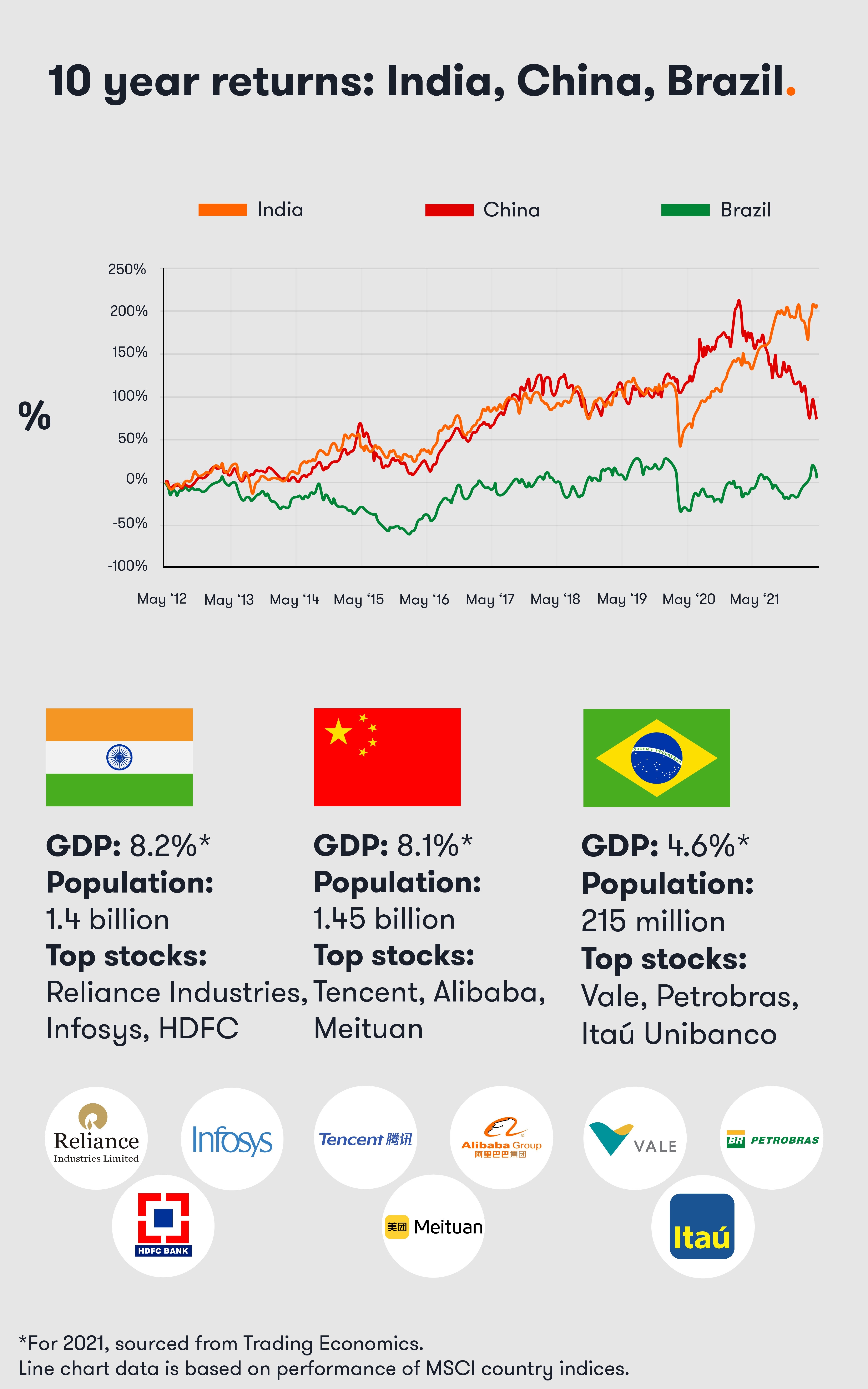

Brazil has suffered from the same problem, with its economy also overexposed to the vagaries of energy prices. So much so that Brazilian equities actually lost money between 2011 and 2021 (and analysts question the sustainability of the world-beating rally seen so far this year).

Against this backdrop, O’Neill himself has been rethinking his original work on the BRICs. In a paper published recently to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the acronym, he argued that while China and India had proceeded on the path of economic development originally envisioned, Brazil and Russia had proved “very disappointing” over the past decade. “This has occasionally led me to joke that perhaps I should have called the ‘BRICs’ the ‘ICs’,” he observed.

Not so catchy, but the numbers tell their own story. The real emerging markets theme of recent times has been the rise of Asia: MSCI points out that the weighting of Asian markets in emerging market indices increased from 59% in 2011 to 79% by the end of last year. Latin America has slipped from 23% to 8%, while Europe is down from 11% to 5%.

“Twenty years on, India and China march on, but the interest in BRIC funds, of which there were many, has certainly waned,” adds Quilter’s Wood. “Perhaps the next decade offers emerging markets a better chance as a result of the benefits that a growing middle class and young expanding populations bring, but it is Asia that is leading this, and, for now, other emerging areas of the world are falling behind.”

- Where to invest in Q2 2022? Four experts have their say

- Funds and trusts four professionals are buying and selling: Q2 2022

Dzmitry Lipski, head of funds research at interactive investor, echoes those views; not least, he points out that Goldman Sachs itself liquidated its own BRIC fund in November 2020, arguing that investors needed a broader strategy for emerging markets.

“It’s not that the BRIC bubble has burst, more that it has slowly evaporated,” argues Lipski. “We still think there is value to be had in emerging markets, but investors need to accept there is going to be more volatility along the way and look to broad, emerging markets funds and investment trusts; the truth is that the ‘I’ and the ‘C’ in BRIC have lived up to their potential, while other emerging markets have emerged that show more promise.”

The bottom line is that while O’Neill’s work back in 2001 made the case for policymakers to think about the BRIC nations in a new way, the adoption of the term by asset managers was more opportunistic. Lipski suggests investors look beyond such marketing. “I would recommend well-diversified emerging markets interactive investor Super 60 rated funds such as JPMorgan Emerging Markets (LSE:JMG), or perhaps the punchier Mobius Investment Trust (LSE:MMIT),” he says. “These can adjust their exposure to a specific region or country as opportunities arise.”

BRICs and ESG

Investors focused on doing good in addition to doing well face some challenges when it comes to emerging markets and the BRICs in particular. If you view your investments through an environmental, social and governance (ESG) lens, are you comfortable about putting money into China’s economy, for example, given the country’s human rights abuses? Are you upset by India’s limited ambitions on climate change, or Brazil’s failure to put a stop to deforestation in the Amazon? Then there is Russia and its murderous invasion of Ukraine.

Even leaving aside criticisms of BRIC governments, there are question marks over the transparency and governance of corporates in these countries. With less regulation of reporting, including on ESG issues, it is hard to get a picture of companies’ performance on many ethical and sustainability issues. The BRIC nations typically score badly in studies of corruption risk.

Still, simply dismissing the BRICs out of hand on ESG grounds feels lazy. China, after all, is a world leader on renewable energy, with businesses that produce more wind and solar power than any other country. Brazil is home to Natura &Co (NYSE:NTCO), the cosmetics group that owns Body Shop and Avon, and which is the world’s biggest B-Corp, or environmentally and socially sustainable firm. Many of India’s leading corporates have set more demanding net-zero targets than their government; Infosys (NYSE:INFY), for example, was carbon neutral by 2020.

The reality for ESG investors, argues Julia Dreblow, the founder of sustainable and responsible investment adviser SRI Services, is that each individual has to make a judgement about their own values.

“Focusing on delivering carefully targeted positive social impacts in countries where there is a challenging political backdrop can be very positive. But it needs to be explained properly so that you know what you are getting,” she points out.

Firms such as SRI can help. It has helped interactive investor’s work to develop its ethical investments long list and its own Fund EcoMarket site offers a tool that enables investors to screen funds by their approach to ESG issues, as well as by region. In emerging markets, for example, it identifies 24 funds that might be of interest to investors with an ESG focus. “There is a good spread of funds with which many ethical investors will feel comfortable,” she says.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.