Big tech: Is the red-hot growth of the technology titans about to cool?

Is the growth in stocks that have powered market momentum over the past five years set to sputter?

15th May 2019 10:58

by Lindsay Vincent from interactive investor

Is the growth in stocks that have powered market momentum over the past five years set to sputter and die? Not according to these big-hitting investment trust managers.

Too large, too powerful, socially irresponsible and not paying sufficient taxes to the societies that feed them. The giants of Silicon Valley have come to live with these and other accusations and, in the main, have stuck two fingers up to critics. But are the most powerful corporate entities in history in danger of being broken up? If their clout were curbed, would this be a negative for investors?

In the front line of the break-up barrage are Alphabet, parent company of Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL), and Facebook (NASDAQ:FB), the social media troika that takes in Instagram and WhatsApp. The verdict on Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) of Bill Simon, former chief executive of Walmart, is blunt.

"Amazon is destroying jobs and value in the [retail] sector – it's anti-competitive, it's predatory and it's not right."

Anti-competitive

Many in the US commentariat and academe agree, as does president Trump, foe of Jeff Bezos, Amazon's all-powerful war lord and the world's richest man. Elizabeth Warren, Democrat senator, consumer rights activist and a contender for the 2020 US presidential election, vows radical reforms if elected.

"They've bulldozed competition, used our private information for profit and tilted the playing field against everybody else."

Few are unaware of the social ills generated among the two billion users of Facebook and its associated apps, such as how to behead an infidel, self-help guides to suicide, child grooming, political influencing and much else. The charge sheet is long and Facebook's sudden commitment, in March, to self-police was inevitable.

In the UK, chancellor Philip Hammond in March pledged to respond later this year to the new, damning review of tech giants by Jason Furman, who was president Obama's chief economic adviser. Furman held that the government needs new powers and a regulator to challenge them. It urged that users should have more control over their data, even charging for its use, and be able to move from one platform to another.

Facebook has done more than any other to persuade politicians to consider laying the basis for regulation of Silicon Valley and the muted reforms suggested by founder Mark Zuckerberg were defensive. Yet some now suspect Zuckerberg has a sly agenda: "a power grab disguised as an act of contrition", in the view of the respected MIT Technology Review. This complex agenda has his reforms enabling Facebook to mirror WeChat, the China phenomenon that one billion use, on average, for three hours a day. Its applications are many, even banking, and the Communist Party can clock every click.

In the EU, Germany's cartel office is investigating whether Amazon has abused its dominant position in internet retailing, as alleged, while the EU Commission is investigating whether Amazon gains advantage from the information it collects from marketplace vendors. The issues have become global and are excruciatingly complex.

France has just imposed a 3% revenue tax on Facebook, which, like Amazon et al, uses sophisticated ruses to shift profit to low-tax centres. The UK has plans for its own tax. But there is no united EU assault. Sweden, protective of its own e-commerce companies, opposes one, while Ireland shivers at the prospect of the EU calling time on its cosy low-tax deals with giants such as Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL). Looking ahead, some feel a universal edict from the OECD countries might be needed for an effective blanket route to curb tax avoidance.

Across the Atlantic, meanwhile, the Department of Justice is in talks with state attorneys-general to glean whether Big Tech is hurting competition while the Federal Trade Commission is circling Amazon.

Significantly, the tech giants' profits are now hovering above a share of GDP that IBM (NYSE:IBM) and Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT) reached in yesteryear, when many clamoured for their break-up. Competition did the regulators' job for them with Microsoft and IBM, but the tech herd's returns on equity now rival those reached by Standard Oil in 1911.

This was broken up into Esso (EURONEXT:ES), Chevron (NYSE:CVX), Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM) and others: easy money reached the table. But AT&T (NYSE:T), the telephony mammoth, delivered much lower returns to its shareholders when trust-busters used the wrecking ball that split its local operations into seven 'Baby Bell' regional phone companies.

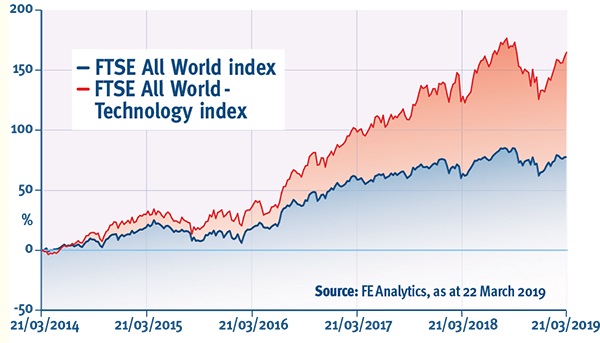

There is much then, to unsettle tech investors, especially given the backdrop of slowing global growth and other woes. And reasons peculiar to each company lay behind last year's savage tech sell-off, when Facebook shares fell by 40%. Yet UK investors in the handful of dedicated technology trusts take comfort from the fact that over the past five years trusts such as Allianz Technology (LSE:ATT) and Polar Capital Technology (LSE:PCT) are among the industry's top performers, returning in excess of 160% to end March.

Technology continues to outperform

Where now?

These past, lucrative five years might yet come to be seen as a golden age and the Big Tech maelstrom will just intensify over the next five years: but investors need not fear the trustbusters. "The argument that they should be broken up is not an argument for not owning them," says James Anderson, co-manager of Scottish Mortgage (LSE:SMT), the chart-topping global trust with approaching half its bets in tech.

"Companies that are broken up have done well: components of Standard Oil rose five-fold after the break-up."

Anderson suspects Amazon would be a huge winner from dismemberment. The share price would go up "a lot" if Amazon Web Services became free-standing; this would force Amazon's "internet infrastructure" to focus on profits. It has consistently been run at around break-even as Bezos strives for world domination. "Any immediate gains from the break-up of Alphabet [Google's parent] would not be so great," he adds.

Anderson believes that regulatory permission for Facebook's 2012 purchase of Instagram and later WhatsApp, in 2014, was "a tremendous mistake. Regulators should have done something then".

However, he backs Facebook's sudden commitment to face up to itself. "I think they know they were wrong, and too focused on the benefits not the downside of communication. It will take at least three years to sort out and they are investing very heavily to do so. That is necessary and important."

Anderson recognises BigTech's tangled status as tax pariahs, brought about by their practice of using all available ruses to transfer profits from where they are made to low tax countries. His solution, to tax profits at source, is unlikely to appeal to Silicon Valley's tax departments. "A 20% rate on profits, not revenues, seems to me to be both practical and a fair balance for society and companies. I'm interested in long term outcomes: as Bezos says the best defence against regulation is popular support. It's silly short-termism to back lower rates than the gains they get from society."

Anderson, whose trust is one of the biggest shareholders in Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA) (funds of his employer, Baillie Gifford are the largest holders, and collectively own more than 7%) is unswerving in his belief that Tesla's electric cars will be Kings of the Road. The key is Tesla's battery technology, which he believes is unrivalled. He has a close rapport with CEO Elon Musk, Tesla's annoyingly peculiar and brilliant inspiration. "He is frustrating and when we challenge him it's an interesting process. He's not a normal person to deal with and we just have to try to deal with it."

Anderson is unswerving in his worship of tech.

"The tech revolution in energy, healthcare and transport is unstoppable."

Ben Rogoff, manager of Polar Capital Technology Trust, follows a single-track road and, unsurprisingly, is more positive about the landscape, including wholesale tax reforms, which he considers "not a tacit risk". Nor, he believes, will an axe be taken to Facebook's corporate structure.

"Facebook bought Instagram when it had zero revenues. Now it is Facebook's engine for growth." Its break-up is "unlikely" he says, while suggesting the case for Google "is more nuanced". The thrust of the argument is direction of trade, he says, but "consumers love them. How did the break-up of Standard Oil make the person in the street feel better?"

Transatlantic contrasts

Significantly, perhaps, the US has traditionally focused on the consumer when tackling competition, but the EU zeroes in more on corporate competition. But historically the tech revolution is probably unrivalled. Attitudes could shift.

"Amazon is causing companies to re-examine themselves. Consumer behaviour is changing," says Rogoff. He also feels Facebook and Alphabet now trade at "undemanding valuations. These incorporate some of the [perceived] risks."

The biggest issue in markets right now is the US/China tariff war, he says, not the risk of a downturn in the US economic cycle. "There are no signs of overheating anywhere; the magnitude of the expansion [since 2010] is extremely elongated. Companies don't really want to add capacity," he says, citing figures for the year to 30 June 2018. Share buybacks by companies in the S&P 500 index totalled $367 billion, a rise of 43%. In contrast, capital expenditure rose by 27% to $317 billion, much of it on 'capital-light' technology spending.

Best opportunities

Rogoff believes the best investment opportunities are now found among US software companies.

"We're heavily into the sector and we've seen 20, 30, 40% growth from some stocks."

The trust was tilted toward smaller companies when Rogoff took over, a decade ago, but now these account for just 2% of the assets.

"I'm not afraid to buy them but the best opportunities are in medium and large cap companies. Internationally, the outcome is winner-takes-all. I also realised I had to make the trust less US-centric. China and the US are where [global] business leadership lies."

Roughly one-fifth of assets are in the Far East, taking in such leviathans as Alibaba (NYSE:BABA), "China's Google", and Tencent (SEHK:700), owner of WeChat and a beneficiary of The Party's decision to ban Facebook from its shores.

Pacific Horizon (LSE:PHI), as its title implies, has a different focus. Technology accounts for some 30% of assets and this bias means the trust is the Asian counterpart of its much larger Baillie Gifford sibling, Scottish Mortgage. "We are one-third overweight," says manager Ewan Markson-Brown. A year ago it was 40% invested in tech but "we've made some changes and some companies underperformed."

Markson-Brown also favours software companies. "Some of hardware's best days [are past] and profitability may decline. Advances in software mean hardware is not always necessary." He cites an innovation by Sunny Optical (SEHK:2382), a key holding that allows pictures to be taken without a camera lens.

He shares the electric vehicle conviction of his colleague, Anderson, but implies that the real winners will be Chinese companies NIO (NYSE:NIO) and Geely (SEHK:175), not Tesla. Models from their new range, perhaps two years away, will be 30-40% cheaper than combustion engines and he disputes Tesla's perceived lead in battery technology. Instead he backs Samsung (LSE:SMSN).

Western fears over China's debts miss the point that all debt is localised, he says, and that a 1997-style Asian collapse is not going to happen in China. He also points out that doing the state's bidding means "companies aim to invest for the social good". Addictive computer games are banned in China: but Tencent gets around this by owning 40% of the hugely successful Sea Limited in Singapore, which fulfils regional demand.

Unlike his counterparts in western markets, Markson-Brown does not fear state moves to break up the tech giants. "Two to three [dominant] companies compete very aggressively. There is no issue with competition" - an irony-of-ironies statement that cannot be applied to the western world of free enterprise.

Big tech still to make its mark in the history books

Commenting on tech's perceived grip on equity markets, Bruce Stout, manager of Murray International (LSE:MYI), a growth and income trust, offers an historical perspective. Real estate and finance were 80% of the US market in the 1800s, he says, and were then overtaken by railways, with 50%. "Today, tech is 25% of the market." The big companies account for 4% of the whole, whereas in their heyday GE, IBM and Microsoft represented 7%, he says.

Stout feels regulators should throw the book at Big Tech. "When companies have a business model that can access people's homes, of course there has to be regulation. Cyber-tech security has to be a threat at some point." Stout, as a former manager of technology funds, knows the terrain and follows the sector "closely".

"The issue for investors is all about current valuations. As long as people act in the way they do, there'll be cyclical profit downgrades. That will happen. The most risky valuations are those for companies with no earnings - concept stocks. Good ideas don't prop up equity valuations for ever. These downturn periods can last a long time."

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.