How to invest in a K-shaped economy

The US is a tale of two wallets, with the top 10% of earners doing half its consumer spending. Here’s why that balance is risky – and how to protect your portfolio if it cracks.

5th December 2025 09:08

by Reda Farran from Finimize

- The top 10% of earners now drive half of all US consumer spending – and that’s making the economy more dependent than ever on the wealthy few

- If asset prices fall, consumer spending could too – and with most people already stretched, there won’t be a lot of demand to break the fall

- A K-shaped economy isn’t a reason to panic. It’s a reason to weigh what’s really driving growth, and build a portfolio that can handle a world where the top arm of the K finally stops climbing.

Not everyone sees the US economy as booming right now, and there’s a good reason for that: it’s gone K-shaped. The wealthy and invested have been watching their financial trajectory rise, while those on the lower end of the spectrum have been seeing theirs fall.

And that formation – a sign of America’s growing wealth inequality – poses a risk for the whole system.

What’s a K-shaped economy, and why is everyone suddenly talking about it?

A K-shaped economy is one where two groups are headed in opposite directions. Imagine the letter “K”: one arm rises, the other drops. That’s the story here – some people and businesses keep gaining ground, while the rest fall further behind. It’s not just inequality in a general sense, but a divergence that gets worse over time – even as economic data suggests things are fine.

The term took off in 2020, when the pandemic recovery split along income and wealth lines. Higher-income households, helped by rising asset prices, bounced back quickly and kept spending. Lower-income households, meanwhile, faced job insecurity and a more severe hit from inflation – and pulled back. Five years later, that split hasn’t closed – it’s widened.

This matters because consumer spending accounts for roughly two-thirds of US economic activity. If the bulk of that momentum is coming from just a thin slice of households, growth starts to look less broad-based and more like a balancing act.

In other words, all the talk about a “resilient” economy is misleading when the averages hide a growing split between the top 10% and everyone else.

Is the US economy K-shaped right now?

The data suggests it’s uncomfortably close – at the very least.

Have a look at the top. Higher-income Americans are keeping the economy afloat by spending heavily, with stock gains, home prices, and cash yields boosting their spending power. That “wealth effect” has made the upper arm of the K pretty sturdy.

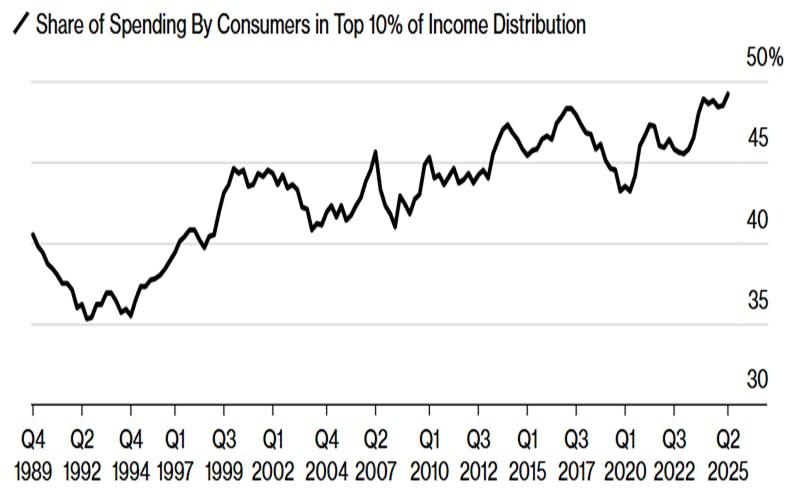

In the second quarter of 2025, the richest 10% of Americans accounted for about half of all US consumer spending – the highest level seen in data going back to 1989 and up from 37% three decades ago. The top 20% drive almost two-thirds of spending. As for the bottom 80%, they’ve steadily lost share: before the pandemic, they made up nearly 42% of consumer activity; now they’re closer to 37%.

The richest 10% of Americans now account for about half of all US consumer spending. Source: Bloomberg.

Lower-income households, whose pandemic-era savings have largely dried up, have been forced to pull back on basics, work more, and juggle steeper borrowing costs. More families are relying on food pantries than just a few years ago. Inflation is well off its 2022 peak, but prices are still high – and pay gains are only just keeping up. And this year, for the first time in a decade of Bank of America Institute data, higher-income workers are seeing faster wage growth than lower-income ones.

What are the economic implications?

A K-shaped set-up changes how the economy behaves – and how fragile it is.

First, growth becomes narrower. When a small group drives half the spending, the economy becomes less about broad demand and more about the health of a wealthy few. So expansions can feel solid, right until they don’t. If the upper arm cracks, there’s no real cushion beneath it.

Second, the economy becomes more sensitive to asset prices. Wealth accumulation has been tied to stocks and housing in recent years, and if those fall – even modestly – spending could drop fast. And that could drag the whole economy down in a swift feedback loop: falling asset prices hurt confidence, people at the top reduce their spending, company earnings weaken, markets fall more, and the cycle feeds itself. In an extreme scenario, it could tip the country into recession.

Third, inflation dynamics get weird. When businesses focus on wealthier customers who can absorb higher prices, the demand signal they get in return becomes distorted. Put simply: they get less pushback when they raise prices, so they keep jacking them up. That leaves inflation lingering, even as the broader economy cools.

And finally, it’s politically noisy. When home and stock values boom for a few, while everyone else feels squeezed, frustration rises and affordability becomes a politically defining issue. We don’t need to take sides to see the market relevance: policy responses (or missteps) become more likely in a split economy.

What does it mean for markets?

Against a K-shaped backdrop, economic data can be misleading. Zoom out, and the big risk is that markets increasingly lean on the spending power of the wealthy few. If stocks or housing cool enough to dent that wealth effect, consumer demand could plummet. And because households from the bottom 80% are already stretched, they won’t be able to provide a buffer.

The “one economy, two stories” setup makes the backdrop tricky to read – and potentially riskier than it seems. Put differently, the odds of a recession might be higher than the data implies.

So whatever your outlook – and wherever you are on the “K” – it’s a good idea to protect your portfolio. Here are three ways to do that:

First, diversify for real. In a top-heavy economy, shocks can spread quickly from markets, to spending, and back again. Investing across a mix of regions and across asset classes can help you offset your losses. Treasuries and gold tend to hold up when stocks, crypto, and other risk assets stumble. And commodities tend to perform well when inflation makes a comeback.

Next, seek out momentum. If a K-shaped economy becomes a downturn, markets may feel it first. That’s where momentum-style risk management can help: when prices trend lower, you scale back. And when they recover, you re-enter. A momentum strategy can be simple and systematic, and can sideline the emotions that could steer you wrong. It won’t help you catch the exact top or bottom, but it will help you avoid getting caught in a long, slow bleed.

And finally, consider hedging. If you’re worried about a sharp market crash, option strategies – like put spreads or deep-out-of-the-money puts – can act as a kind of insurance. Ideally, you’ll never need it. But if you do, it’ll be worth every penny.

Reda Farran is an analyst at finimize.

ii and finimize are both part of Aberdeen.

finimize is a newsletter, app and community providing investing insights for individual investors.

Aberdeen is a global investment company that helps customers plan, save and invest for their future.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.