Could this risky approach solve the UK’s productivity puzzle?

Politicians believe they have a solution to one of the longest-running problems in British business. Analyst John Ficenec discusses potential benefits for both workers and shareholders.

15th October 2025 12:23

by John Ficenec from interactive investor

Commuters crossing London Bridge: Picture: Bim/iStock

A radical change to how Britain goes to work will take place within weeks, but will this sea change in working relations be a hammer blow for British business or could it finally solve the intractable productivity problem?

- Invest with ii: SIPP Account | Stocks & Shares ISA | See all Investment Accounts

Britain’s not working

The UK does have a problem - we’ve been working longer hours and getting nowhere. The issue for the UK is that the productivity puzzle is more than just an abstract economic policy headache, it is becoming an existential problem. Without growth we have no chance of paying back our national debt, and with yields soaring on UK gilts the cost of servicing that debt is getting more expensive by the day.

The answer, it’s hoped, is the Employment Rights Bill, one of the central pillars of Labour policy. With it they are trying to solve one of the longest running headaches in British business. Since the 2008 banking crisis, we have lagged our European neighbours, and our transatlantic cousins, in terms or productivity.

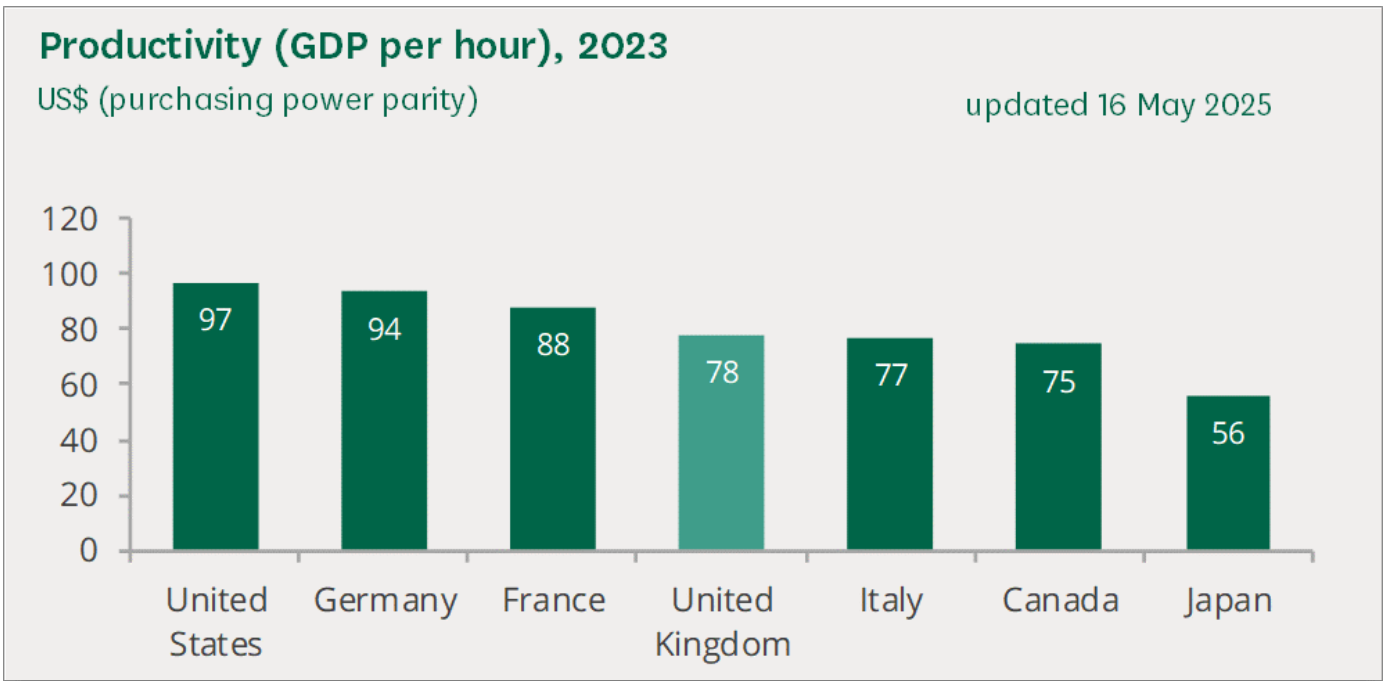

The issue is a huge handbrake on the economy; for every hour worked we make 20% less than the US and Germany, and around 10% less than France, according to the most recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) analysis.

Source: OECD, productivity levels.

International comparisons

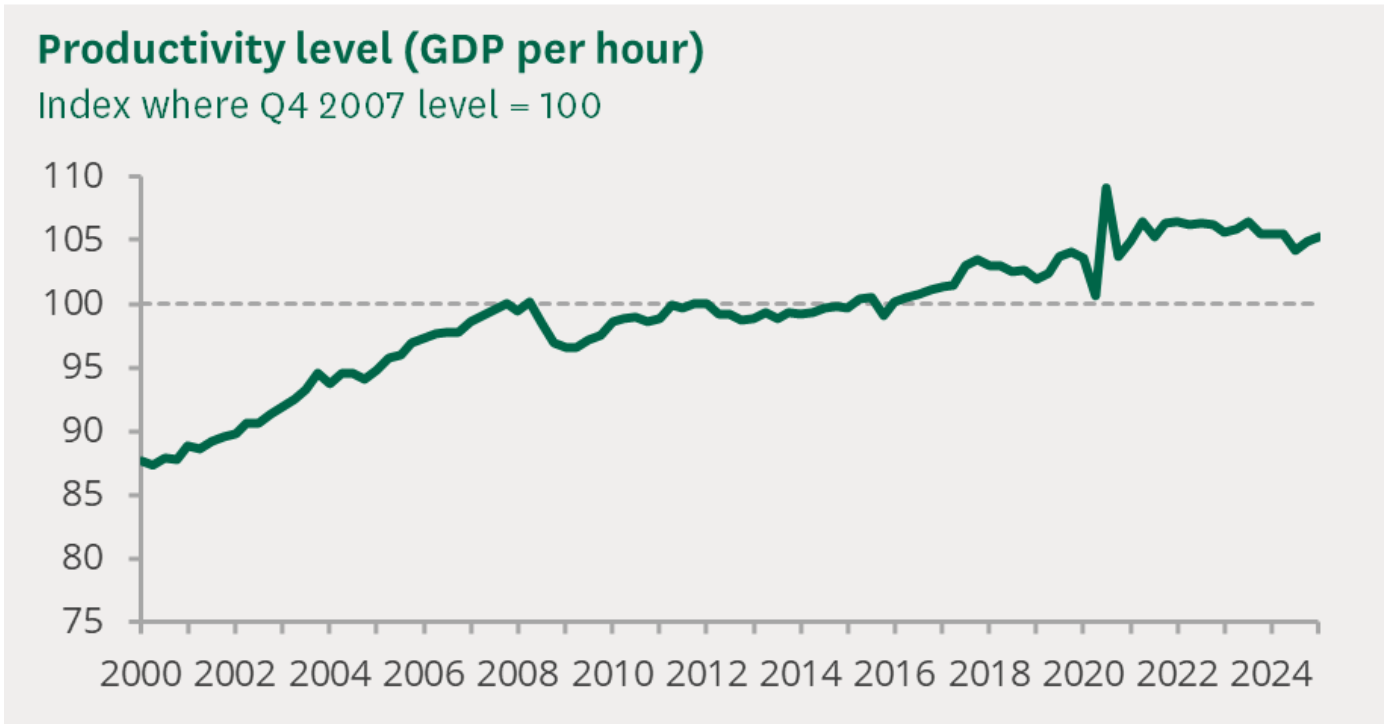

In terms of progress, since 2008 there has barely been any, with productivity per hour worked crawling along at a blink-and-you-miss-it 0.3% per quarter for the past 17 years, and that compares to growth of 2.3% per quarter over the same period before 2008, according to Office for National Statistics (ONS) data.

As a nation, we are now working with all the technological benefits of the internet, smartphones, Wi-Fi connectivity and cloud computing with barely anything to show for it.

Source: ONS, series LZVD (rebased), and Library calculations based on ONS flash estimate for Q1 2025.

According to Professor Jon Van Reenen, head of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance, if British workers could be as productive as those of Germany or France, we could take every Friday off and still earn the same amount of money as we do now.

That’s if we even make it into work, with the average employee now taking almost two weeks of sick leave during the past 12 months, the highest level in 15 years, according to latest figures from Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD). The report also found mental health issues were the leading cause of absences of more than four weeks.

At your service

The UK is one of the most exposed economies in Europe to issues of worker productivity because it is so heavily dependent on the service sector. As a country we used to make things, and in 1948 the economy was split around 46% in services and 42% in production, which included manufacturing. Roll forward to today and 81% of the economy is services with just 8.8% manufacturing, according to ONS data.

The largest constituents of the service sector are Retail, Leisure, Care, Transport and Accommodation, which when combined contribute around a quarter of the UK’s economic output. The problem with these industries is that they are characterised by lower wages, skills and qualifications, all of which meant they were the most exposed to the aftermath of the 2008 crisis.

Pub worker pulling a pint. Photo: Drazen Zigic/iStock

The compromise of crisis

When the music stopped in 2008 and everyone realised that making new financial products out of loans nobody could afford was a bad idea, it was those in the service sectors that were hit hardest.

The government of the time persuaded us that the chirpily titled “gig economy” would remove the barriers to economic growth and allow the recovery to accelerate. And while I’m sure a more relaxed approach to employment suits a minority, the problem was companies used the new laws to force millions into the gig economy whether they liked it or not.

Under the current conditions, in the worst cases a job can mean very few, or no hours at all, at any location chosen by a company and at any time of day, with no holiday pay, sick pay, or opportunity to voice concerns about working practices without the risk of dismissal.

- Shares for the future: this new stock replaces a FTSE 250 firm

- Sign up to our free newsletter for investment ideas, latest news and award-winning analysis

Under such conditions it’s easy to understand how those in the service sector might not bring their best self to work, and even if they wanted to it’s easy to see how they might not be able to deliver their best. This gets us to the crux of the UK productivity conundrum, that perhaps people cannot be more productive under these conditions because there has been a fundamental breakdown in the unwritten agreement between employer and employee that each will treat the other with a degree of fairness.

There are other factors that have been blamed for the UK’s productivity shortcomings, such as chronic under-investment in new technology, equipment and practices, alongside an over-reliance on more inexperienced staff, but these seem to all be secondary to having employees that have lost faith in their employer.

Reform to the rescue?

It is with this in mind that the new employment reforms come hurtling over the hill. The aim is to try and tackle some of these structural issues in the UK labour market. Given the lack of progress since 2008, it is probably time to try something different.

Some of the key elements of the new bill are to remove so-called zero or low hours contracts, improve unfair dismissal rights and sick pay from day one, and making it easier to join trade unions and take industrial action.

There has been intensive lobbying from business against the bill, and the House of Lords attempted to water down many of the key elements, but the Commons recently rejected these. The bill is now in its final stages and due to return to the Lords on 28 October for what looks like the final time, so that now gives us a pretty clear indication that the final bill will largely be unchanged from today.

The timeline has been staggered so that business can adapt to the new measures. Once the bill is written into law this autumn, then the first changes to make industrial action simpler are expected before the end of this year.

- The first five years of retirement: are you prepared?

- Stockwatch: is recent bolt of panic a warning sign?

The next milestone is thought to be April 2026 when more workers will be made eligible for sick pay and paternity leave, with whistleblowing protection strengthened.

Then in autumn next year “fire and rehire” will be stopped, and tipping made fairer for restaurant staff.

Finally, in 2027 the two measures likely to hit business hardest, bringing in guaranteed hours contracts, and compensation for cancelled shifts will be brought in.

Worker re-stocking supermarket shelves. Photo: Hispanolistic/iStock

The price of change

The new policies in the bill do not come without risks, and it is expected that it could cost between £0.9 billion to £5 billion a year to British business, according to the Department for Trade. This is a serious concern as the analysis also shows that it will hit small- and medium-sized businesses hardest, just at a time when they are already struggling.

The sectors that will have to adapt are those that rely on large numbers of shift-based staff, not the white collar 9-5 office workers. In the retail world it will be names such as electronics giant Currys (LSE:CURY), Frasers Group (LSE:FRAS), the owner of Sports Direct, also WH Smith (LSE:SMWH), JD Sports Fashion (LSE:JD.), Next (LSE:NXT), Wickes Group (LSE:WIX), and B&Q and Screwfix owner Kingfisher (LSE:KGF).

The Leisure sector also leans heavily on shift staff where pub groups such as Wetherspoon (J D) (LSE:JDW), Mitchells & Butlers (LSE:MAB) and Young & Co's Brewery Class A (LSE:YNGA) will face pressure. Supermarket giants Tesco (LSE:TSCO), Sainsbury (J) (LSE:SBRY) and Marks & Spencer Group (LSE:MKS) rely on thousands of lower-skilled workers.

Support services is another industry that requires flexible, mobile staffing so Serco Group (LSE:SRP), Bunzl (LSE:BNZL), MITIE Group (LSE:MTO), Compass Group (LSE:CPG) and Rentokil Initial (LSE:RTO). One of the biggest perhaps is logistics giants such as Amazon.com Inc (NASDAQ:AMZN), which is one of the top 10 private sector employers in the UK.

- FTSE 100 dividend stars: City view on M&G, Phoenix and L&G

- The AIM miners that are this year’s hot stocks

Now the shape of the employment rights bill has crystallised as it reaches the final stages of the political process, companies can begin frantically working out the cost implications. Removing the ability to outsource the cost of changing consumer demand on to their employees will be painful. Most employers have already distanced themselves from exploitative zero-hours contracts as they are so damaging to the public image, but low-hours contracts are still widely used.

In the short term, it’s likely there would be an uptick in unemployment if the customer demand remains stable as employees asking for more hours would mean a requirement for fewer staff. This would be largely neutral on a cost basis, the piece that would introduce a large amount of cost is the administrative and planning required when fewer staff working longer hours make shift patterns more inflexible.

But this is clearly a price worth paying as the prize on offer is vast, as if productivity levels returned to pre-2008 levels the economy would be one of the fastest growing in the G7.

Certainly, many of the measures in the bill would simply be matching employee rights that are already in existence in both Germany and France.

Broken labour market

It’s clear something fairly significant broke in corporate Britain in 2008 and until now we’ve managed to muddle through with some quick fixes, shallow promises and throwing increased spending at the problem.

We are now fast running out of road and time to try alternative options, as the rising cost of borrowing raises questions about our national debt pile. The UK is not alone, governments in France, Spain, Greece, Italy and the US are all grappling with some of the highest levels of debt in their history.

The risk of adopting innovative fiscal solutions have been laid bare in Argentina, where President Javier Milei appeared on TV with a chainsaw promising to cut spending and economic orthodoxy. Initial success saw inflation fall last year, but as the value of the Argentine peso collapsed, Milei had to seek a $20 billion (£15 billion) rescue package from the US in recent weeks, showing just how quickly government finances can unravel. In France, the government has collapsed merely over suggestions of not maintaining spending at the current rate, never mind cuts.

The employment bill is no quick fix to a problem that has been 17 years in the making; if anything, it looks likely to make things slightly worse before they get better, and the service sector will face headwinds throughout next year as each phase of the new law is applied.

However, the potential reward for the UK economy is so great it’s a risk worth taking. If there is even the slightest improvement in productivity, and labour market relations can begin to be repaired, then both workers, and shareholders will benefit handsomely. Trust will not return overnight, and high degrees of scepticism are to be expected from all sides, but fixing these labour market issues will provide a solid platform for a rerating of the whole UK economy.

John Ficenec is a freelance contributor and not a direct employee of interactive investor.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.