How pensions windfall could turbocharge UK stock market

For years, UK companies were weighed down by massive pension deficits. But times have changed, and investors could benefit. Analyst John Ficenec investigates.

24th September 2025 14:21

by John Ficenec from interactive investor

The UK economy could get a helping hand from the most unlikely of sources as huge surpluses build up in company pension schemes. For years pension funds have been a millstone round the neck of corporate Britain, but huge funding programmes and market shifts have finally turned the tide.

- Our Services: SIPP Account | Stocks & Shares ISA | See all Investment Accounts

Pensions pot of gold

There is an estimated £160 billion sitting surplus in corporate pension funds which could be returned to the members and used to fund growth, according to latest figures from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). Looking at the UK blue-chip index, the FTSE100, there is a surplus of over £40 billion, according to pensions specialist Lane Clark & Peacock (LCP), which could be released under new laws.

One of the driving factors behind the reversal of fortunes has been soaring yields on UK gilts. Rising yields have greatly reduced the amount that defined benefit, or final salary, pension schemes need to meet payments in the future.

Rising returns

Imagine you are expecting to receive £20,000 a year as your final salary pension. If UK gilt yields are around 1%, as they were just four years ago, you’d need £2 million in the pot to buy enough gilts to generate your required annual income, but with yields at around 4.5% today, you’d only need around £440,000.

- Interest rates held as inflation threat persists

- Is global bond market sell-off a golden opportunity?

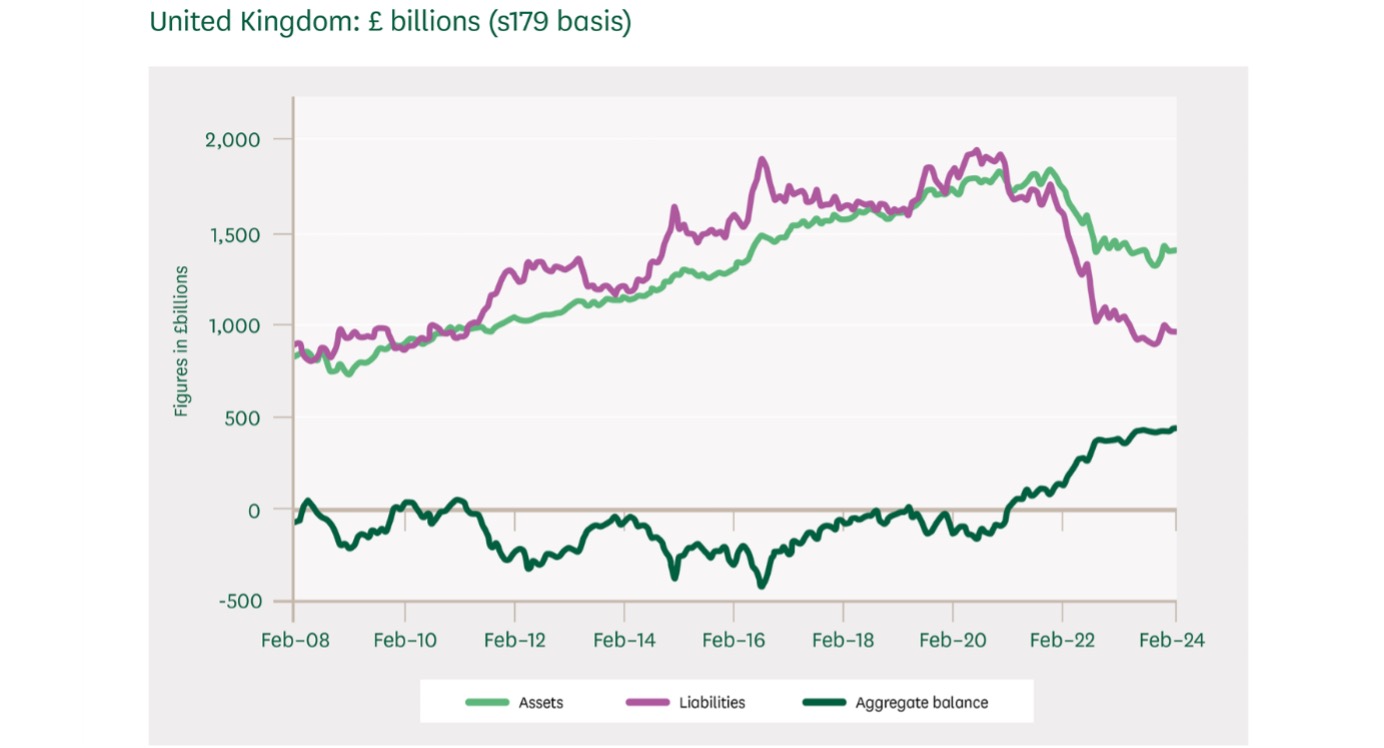

It’s true that as gilt yields have risen then the assets in pension funds have fallen as well, because as yields rise the price of gilts fall. But crucially, not all the assets in pension funds are held in gilts, with around a fifth of pension fund portfolios held in equities in 2021, according to DWP analysis. So, with stock markets around the world rising to record highs during the past four years, this has offset some of the reduction in value of the fixed income, or gilt, portion of the portfolio. Importantly, what has to be paid out, or the liability, has fallen much further than the pension pot, or the assets.

Source: House of Commons Library, based on Pension Protection Fund’s PPF 7800 index.

As recently as 2018, just over half the FTSE 100 constituents (51 companies) reported a pension deficit. But that has reversed to 80% of companies reporting a surplus totalling £40 billion at the end of last year. Across the FTSE 350 index, the surplus sits at £80 billion, according to consultancy Mercer. This is no flash in the pan; a surplus has been reported for FTSE 100 companies for the past five years, with the average now at £600 million, according to analysis from LCP.

This theme is not unique to the UK’s blue-chip equities index and is replicated across the almost 5,000 defined benefit pension funds, which reported a surplus of £220 billion at the end of last year, the DWP showed.

Looking at one example in particular shows the dramatic changes that have taken place in the pensions landscape. In 2018, defence contractor BAE Systems (LSE:BA.) had a yawning £4.2 billion deficit in its pension, and this was against the company’s market value of around £15 billion.

Fast forward to today and there is a £1 billion pension surplus on the books, while the shares have surged to give a market value of £58 billion. It’s not just market movements that have helped close the gap; a lot of heavy lifting has been done by the companies themselves.

Source: interactive investor. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

Between 2007 and 2020, it is estimated that UK companies spent over £200 billion plugging the gap in their pensions funding after share prices fell sharply following the 2008 banking crisis, and gilt yields were fixed to below 1% during the subsequent bailout.

Pensions headache

The tricky question now is how best to access these funds, or if they should be accessed at all, and who they belong to? One fairly fundamental question is whether the surplus exists at all, given that it is based on accounting estimates.

To work out how much money is needed in the pension pot, you have to guess how long people will live for, the rate of inflation during that period and the yields on government and corporate bonds in the future. As we’ve seen, small movements in those assumptions can cause huge changes in the final values.

It would make no sense at all to take hundreds of billions out of pensions purely based on an accounting estimate, only for the company to collapse a year later if the market and accounting estimates change. But, equally, having billions sat on company balance sheets when those funds could be invested to drive growth, makes even less sense. A balance needs to be found.

The size of the potential prize is huge, as with schemes in surplus they could find other uses for the almost £15 billion in annual deficit support payments that have been paid each year to fill past gaps. There is also around £160 billion that is now sat on balance sheets.

- Retirement case study: how I manage a £2.5m SIPP and ISA portfolio

- What to consider before gifting your pension to swerve IHT

Who it belongs to is also worth considering. Should it be given to the scheme members to boost their final salary schemes, or should the company that has paid in billions to fill the gap use those funds to drive growth? Or, given that the higher gilt yields that have seen future liabilities fall so sharply mean an increase in the cost of government borrowing and national debt, should some of this surplus be returned to government and the taxpayer? As football managers with a strong subs’ bench are want to say, it’s a nice problem to have.

It is exactly this complex set of demands and opportunities that are trying to be resolved as the pension reform bill currently winds its way through parliament. It is expected to receive Royal Assent next year. What will follow is some horse-trading on how the regulations are changed, with the earliest likely release of funds towards the back end of 2026, and into 2027.

So, while it’s not an imminent release of cash, markets tend to price around 12 months in advance, so as the terms of the bill crystallise in parliament and draft regulations begins to be aired, it could start to be materially important for share prices.

Certainly looking at the FTSE 100, there were just five companies that are responsible for more than half of the £40 billion surplus in pensions: HSBC Holdings (LSE:HSBA), NatWest Group (LSE:NWG), BP (LSE:BP.), Barclays (LSE:BARC), and Lloyds Banking Group (LSE:LLOY), according to LCP and, while some companies have smaller absolute surpluses, for example Sainsbury (J) (LSE:SBRY), and Associated British Foods (LSE:ABF), their pensions surplus makes up over 8% of the market value of the company.

Summary

For decades the pension problem has hung over the FTSE 100 and weighed on the valuations of UK equities. A pension deficit is a problem that sits very high on a company’s list of priorities, it has to be sorted before cash can be returned to shareholders through dividends, and before cash can be spent on new projects to grow the business. It hurts the value of shares because it is also a cash problem as the company must make payments every year until the deficit has gone.

Taking BT Group (LSE:BT.A) as a quick example, it had a pension deficit of £4.1 billion in the year ended March 2025, down from £4.8 billion a year earlier. To solve the deficit, it made cash payments into the pension fund of £803 million and is forecast to make similar payments for the next five years. Putting that in perspective, BT paid out dividends of £788 million last year, or around 8.1p per share, so solving the pension problem could release a huge amount of cash to return to shareholders, and would also add around 8p to earnings as the deficit payments are an expense and reduce profits.

- Sector Screener: two FTSE 100 stocks with long-term investment potential

- Sign up to our free newsletter for investment ideas, latest news and award-winning analysis

There is the potential for some good news on the horizon as well because corporate pensions are subject to valuations every three years, and BT in particular is due to complete their next one by June 2026. The current revaluation of the pension fund would reflect the drastic moves in gilt markets.

While I wouldn’t invest purely on this basis, as pensions actuaries are want to be conservative and are unlikely to rubber stamp a large cut in deficit funding, with a company like BT and the wider UK market in general, it’s something that could provide support to valuations and a re-rating going into next year. So, I’d be happy to look at some of the unloved UK equities now this pension headache is clearing.

John Ficenec is a freelance contributor and not a direct employee of interactive investor.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.